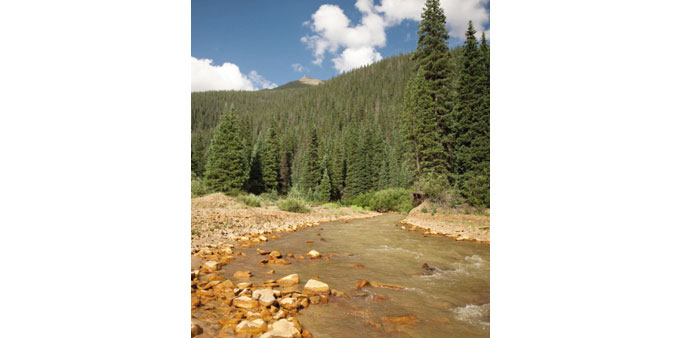

Cement Creek, which was flooded with millions of gallons of mining wastewater, is stained orange on Tuesday in Silverton, Colorado.

Reuters/Durango, Colorado

The water quality of a southwestern Colorado river rendered bright orange by toxic waste spewed from an abandoned gold mine one week ago has returned to pre-spill levels, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) chief said on Wednesday.

The statement from EPA administrator Gina McCarthy, whose agency has assumed responsibility for inadvertently causing the spill, came as Colorado health officials cleared the way for the city of Durango, just downstream, to reopen its drinking water intakes from the river.

McCarthy also ordered the EPA’s regional offices to immediately cease further inspections of mines or mine waste sites, except in cases of imminent risk of danger, during an independent review of the accident.

More than 3mn gallons (11.3mn litres) of acid mine sludge were accidentally released from the century-old Gold King Mine near Silverton, Colorado, during work by an EPA crew to stem seepage of wastewater already occurring at the site.

“The EPA does take full responsibility for the incident,” McCarthy said during a visit to Durango, a resort town popular for its rafting and kayaking about 50 miles (80km) south of the spill site on the Animas River, which was the hardest hit.

The torrent of waste unleashed by a breach of a tunnel wall on August 5 gushed first into a stream just below the site called Cement Creek before washing into the Animas, turning both bright orange.

From there, the waste flowed into the San Juan River, a Colorado River tributary that winds through northwestern New Mexico into Utah and ultimately joins Lake Powell.

The EPA has previously said that state, local and federal authorities had agreed to keep the Animas and San Juan rivers closed to all fishing, recreation and intakes of water for drinking and irrigation until at least August 17.

Water samples taken from the upper Animas last week when contamination was at its peak showed arsenic concentrations as high as 1,000 parts per billion, or 100 times the maximum level set by the EPA for drinking water.

But with subsequent samples showing traces of heavy metals and other contaminants back at pre-spill levels in the Animas, state and local governments were now at liberty to lift restrictions on that river as they see fit, McCarthy said.

“We let the science be our guide and we work with our partners,” she said.

While giving Durango the OK to resume its intake of river water for municipal treatment, state health officials urged all private drinking wells within a mile (1.6km) of the Animas to be tested before use.

They said, however, there was no indication of any groundwater contamination.

No evidence of harm to human health, livestock or wildlife has been reported.

Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper said earlier in the day that the Animas appeared to have returned to normal, with no sign of lasting environmental harm, though EPA officials and toxicologists have warned that long-term effects of the spill remain to be seen.

Dilution has gradually diminished concentrations of contaminants such as arsenic, mercury and lead.

However, experts say that deposits of heavy metals have settled into river sediments, where they can be churned up and unleash a new wave of pollution when storms hit or rivers run at flood stage.

Besides metals that are outright toxic to aquatic life, the iron compounds that turned the water orange can smother plants and habitat as they sink to the bottom.