By Andy Home/London

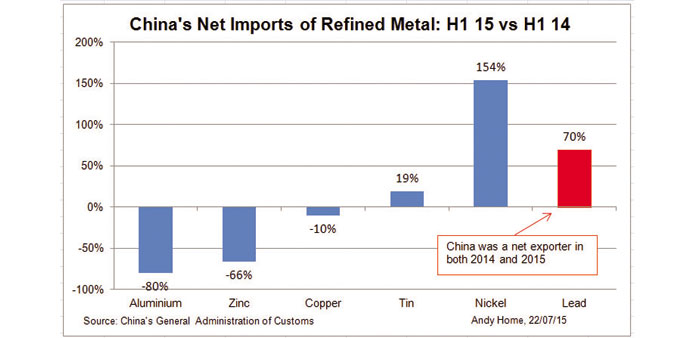

China’s pull on refined metal from the rest of the world was much diminished in the first half of this year. Imports of aluminium, zinc and copper all fell, sharply in the case of the first two.

Financial demand for metal as collateral against loans has been much diminished since the Qingdao port scandal in the middle of last year.

Manufacturing demand, meanwhile, has also softened in tandem with the broader slowdown in the Chinese economy to the point that analysts at Goldman Sachs argue that metals demand has experienced a “hard” landing in the first part of this year.

Underlying both trends is China’s gradual shift towards self-sufficiency at the refined metal stage of the supply chain.

When it comes to lead, for example, China is now a consistent net exporter, albeit still a fairly marginal one.

And although tin imports were up almost 20% year-on-year at 4,400 tonnes, that’s a low figure by historical standards as the country’s tin smelters continue to suck in raw material from neighbouring Myanmar. The stand-out exception to the first-half picture of slowing imports was nickel.

Even here, though, there is sufficient ambiguity to be wary about extrapolating a trend from June’s bumper imports.

Net imports of refined nickel more than doubled to 78,100 tonnes in the first six months of 2015. In truth, imports had been running at pretty humdrum levels until June, when they went stratospheric.

June’s imports of 38,800 tonnes were the third highest monthly tally on record after June and July 2009.

This, it’s worth remembering, is exactly what nickel bulls had been hoping to see.

Imports of nickel raw materials are still falling, down 37% in the first half, with flows of Philippine ore failing to fully fill the gap left by the Indonesian ban on exports. The pressures on China’s nickel pig iron (NPI) producers are building as inventories of Indonesian ore run down and the current low price environment forces out marginal operators.

Logically, the less nickel China produces, the more it will need to import, which is why bulls have seized on the latest figures as a sign of things to come. This process has already been playing out in ferronickel, a cheaper and more obvious NPI substitute for stainless steel mills. Ferronickel imports also more than doubled in the first half of this year and were running at a record pace of over 60,000 tonnes per month in both May and June. So is that import demand now spilling into the refined metal market, offering bulls the tantalising hope that the seemingly endless rise in London Metal Exchange stocks might be about to turn?

The answer right now is only maybe.

June may yet turn out to be something of an outlier month with surging refined nickel imports reflecting factors other than pent-up manufacturing demand.

It’s noticeable, for example, that imports from Russia at 21,700 tonnes hit an all-time high. And that may have reflected the well-flagged delivery issues around the recently-launched nickel contract on the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE).

Concerns about a potential squeeze on the contract were stoked by the fact that only Chinese brands were initially deliverable.

Russian brands have now been added to the list, incentivising the movement of Russian metal into China to be lined up for physical delivery against the SHFE July contract.

SHFE stocks are still low at 13,679 tonnes, compared with 10,000 tonnes when the contract was launched in April.

The next couple of weeks will tell whether what has been imported turns up on the SHFE, in which case it will amount to no more than a relocation of stocks, or whether June did indeed mark a change of underlying trend.

But it’s understandable that the market, which has for so long been geared to drawing bullish succour from China’s imports, should have focused on nickel.

Because imports of just about everything else were weaker in the first half of this year. Aluminium and zinc registered declines in net imports of 80% and 66% respectively. Both may be suffering from the long tail effect of last year’s Qingdao port scandal, involving the multiple pledging of metals for loans.

The subsequent collective tightening of credit for such collateralised deals has dampened financial demand for two metals which are in ready supply within China.

After all, it’s hard to make a case that China really needs more aluminium to fill any domestic supply-demand gap when the country is pumping out ever greater amounts of semi-manufactured products.

This outbound flow of product, which benefits from tax rebates unlike primary metal which is subject to an outright export duty, is still accelerating.

Exports rose to 2.2mn tonnes January-June from 1.54mn tonnes in the first half of last year.

Similarly with zInc China’s own production is soaring, up 13% in the first half of this year, thanks in part to strong imports of zinc raw materials. Zinc concentrate imports jumped by over 50% to 1.42mn tonnes, a warning sign for those who believe that raw materials shortfall is just around the corner in this market.

*Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The opinions expressed are his own.