Into his 35th year of ghazal singing, the maestro explains to Umer Nangiana how he manages to put soul into it, and the reason why he leaves room for innovation

Every time he renders his vocals to a ghazal or a geet (genres of sub-continental music), he ensures a remarkable level of spiritual tranquility. It is what makes him Pankaj Udhas, now a holder of the fourth highest civilian award in India, the Padma Shri.

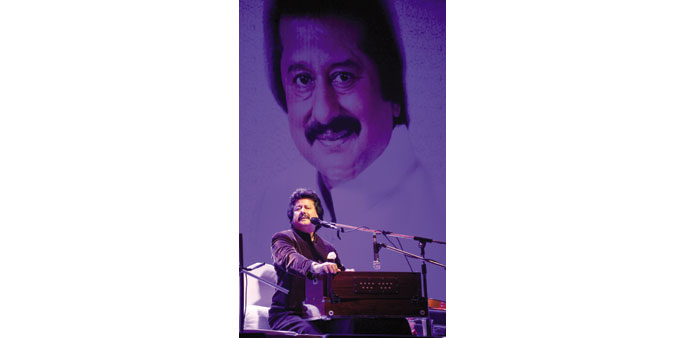

Having Padma Shri Pankaj Udhas unplugged, however, is a treat unheard of. Every ghazal-lover would die for one such chance at least once in a life time. Some in Doha were fortunate to have it. The ghazal maestro was here in concert one blissful evening recently.

The ambiance at the state-of-the-art concert hall of DPS-Modern Indian School Doha started building up with the arrival of musicians on stage, dimly-lit with multi-coloured lights dancing all around.

Attired in a traditional but elegant black kurta shalwar, Udhas took to the stage and sat behind his harmonium (traditional musical instrument) under the spotlight amid applause from a packed house.

He began the rites of passage with renowned Urdu poet Nasir Kazmi’s popular ghazal Dil dharhakne ka sabab yaad aya (why my heart skipped beats, I recalled). And the spell began. The music was his signature mix of a bit of popular with eastern style — the latter predominant with harmonium, tabla and flute (traditional musical instruments).

“This is my 35th year of ghazal singing and I am truly thankful to you all for your love and support all these years,” the maestro said to an extended applause. To their elation, Udhas chose Sab ko maloom hai main sharabi nahin (Everyone knows I am not a drunkard) for his next track. The house went in chorus.

Keeping the flow, the musicians in the ensemble chipped in with jugalbandi (a duet of two solo musicians), first the tabla and violin, followed by tabla and flute. With his eyes shut and head swinging with the melody, at this point it seemed Udhas had started enjoying his own voice, the music and the ambiance these created.

How does he manage to put soul into his singing, I asked having caught up with him backstage for a brief chat.

“It is something that is positively inbuilt, not something that I have adopted or practised,” the maestro replied.

As a child he grew up with a certain connect with all those singers who sang soulfully. Udhas particularly named legendary singers Talat Mehmood, Mukesh, Muhammad Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar whose songs taught him how soul is mixed with music.

“Listen to Yeh mera deewana pan hai, for instance — you would feel Mukesh-ji has put his soul into it. The same way I remember listening to film Anari’s song Tera jana dil ke armanon ka, and I felt how could Lata-ji express herself like this,” the ghazal maestro pondered before adding, “So I feel it is something that I grew up with as a child. And then it probably became an integral part of my system.”

He also credited the use of a taanpura (a traditional supporting stringed instrument) and a brilliant team of musicians. “I guess we create a kind of an atmosphere on stage that after about the initial 20-25 minutes, we completely forget we are in front of an audience, we are on stage, we are trying to do a professional job for which we are being paid and we enjoy the experience,” Udhas smiled.

Lapse back in time and the audience back in the hall a few minutes ago were rejoicing listening to some of his best. Bohat khoobsurat ho tum (you are truly beautiful), Deewaron se mil kar rona acha lagta hai (It feels good to weep in solitude) and his signature ghazals like Mehngi hui sharab ke thori thori piya karo (Don’t drink in excess, wine has gone expensive), La pila de saqiya paimana paimanay ke baad (pour me a glass after glass of wine) were just relived live.

But there was still room for suspense. Would he sing one of his evergreens, Chandi jaisa rang hai tera, soney jaise baal (Your complexion is as expensive as silver, your hair as gold)? And he did. The house went up in whistles and rhythmic applause, all in chorus.

Growing up at a time when Bollywood music was all the rage, how did he come to ghazals, a different genre?

Udhas credited his eldest brother Manhar Udhas, himself a noted singer, and his family in general for it. Manhar, he narrated, decided to pursue singing — much to his family’s shock— after completing his engineering and moved to Mumbai. Then he called the entire family there.

Manhar as someone from Gujrat was advised to take lessons in Urdu and a teacher used to come home to teach him. Udhas used to see the Ustad (teacher) describing poets like Ghalib and Daagh to Manhar. “I was awe struck. So one day, I gathered all the courage and I asked the Maulvi sahab (the teacher) if he could teach me Urdu,” Udhas recalled.

The teacher hesitated, probably surmising Udhas with a streak of modernity may not be serious. However, he convinced the teacher.

“So when he started teaching me that was the time when he introduced me to Begum Akhtar (a legendary ghazal singer from sub-continent) and I think Begum was the first person, who touched me right here (pointing to his heart) and I have lived with her music all my life,” Udhas said of his introduction to ghazal.

“Ghazal is not just a profession or career for me. It is much more. I am so very passionate about the whole genre of ghazal that I think I live and breathe it,” said Udhas.

Practising ghazal for over three decades, Pankaj Udhas can easily be counted as one of the living legends in the genre. He can also be credited for playing a major role in popularising the genre of ghazal among the youth — thanks mainly to his innovation with traditional musical style.

“I have been revolutionary in my work. I have always taken liberties only for one reason: my passion is endless and I always wanted that this particular genre of ghazal should go far and reach out to as many people as possible,” Udhas said of his experimentation with the music.

Talking of which, Udhas would probably be the only ghazal singer, who has mixed an Italian origin instrument, mandolin, with the more traditional ghazal music instruments. But then his mandolin player, Nasir Sajjad, was unique.

It was a whole new experience seeing Nasir getting into a duet with tabla players during some of the performances. Mandolin music gelled in with the rest of the instruments to give ghazal music a new look.

How did he manage it?

“Nasir’s father Sajjad Hussain was one of the most respected music directors of our industry. He was also a mandolin player and it is rare that you would find someone playing Indian classical music on mandolin,” Udhas elaborated.

“As mandolin is an instrument which is always played in a certain style, Sajjad started the tradition of playing Indian classical ragas (melodic modes) like gamak, meendh, dari on a mandolin which was never heard of,” he said.

“So Nasir has adopted the same technique. He was taught by his father and when you listen to his mandolin, it sounds like a combination of sarod, rubab (traditional sub-continental instruments) and a mandolin. His tone is so beautiful and he emotes so much through his mandolin and that is one of the reasons he is playing with me,” Udhas explained.

Like the selection of poetry for his ghazals, Udhas’s selection of tracks for the night was right in sync with the audience’s mood and the overall environment. While he entertained them with his hit songs, he touched the softer parts of their hearts with more melancholic melodies rekindling the memories of homeland.

Chithi ayi hai (A letter has arrived — from home) was one of them. People demanded it and he delivered.

What is more important in ghazal singing, a good tabla player or selection of poetry?

“I would say it is poetry positively — as they say, content is the key. All my seniors, be it Pakistan’s Mehdi Hassan and Ghulam Ali, and our own Jagjit Singh, all of them have held selection of poetry superior,” Udhas reasoned. He also believed there were fairly large number of good contemporary poets in both India and Pakistan to provide content for ghazals.

Obliging all in the audience by singing a couplet from the ghazals they had requested, Udhas concluded the night on a perfect note, Ghunghru toot gaye (The ghunghru broke — ghunghru is a musical anklet tied to a classical dancer’s ankles).

BELOW:

1) LAUNCH: Pankaj Udhas officially launches the brochure before the concert with other officials of the DPS-Modern Indian School Doha.