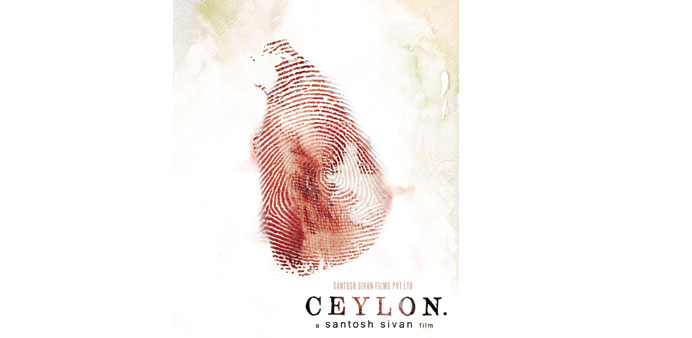

APPREHENSION: Exhibitors in Chennai were nervous about releasing Santosh Sivan’s latest, Inam (Ceylon), last week. It talks about the suffering of Tamils in Sri Lanka.

By Gautaman Bhaskaran

Often the most inane of issues grip people’s imagination in India, driving them to anger and destructive behaviour. And not just the people, but the government too gets defensive. While, for instance, there are a whole lot of civic issues that can well do with attention, cinema seems to grabbing the eyes and ears of the citizen and the administrator.

Recently, India’s Central Board of Film Certification refused to allow the public screening of the documentary, No Fire Zone: The Killing Fields of Sri Lanka – which looks at the last phase in early 2009 of the ethnic war between the island nation’s army and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, seeking a separate homeland for the minority community. (Sinhalas form the majority in the country.)

Although the movie has been in the public domain for more than three years, Colombo has been lambasting it, calling the documentary propaganda to shame the Sri Lankan administration.

After India’s Censor Board refused to certify the film, the director of the documentary, Callum Macrae, said his work would now be freely available on the net in India. It will be in English with Hindi subtitles. And the documentary has since then been widely seen.

In recent years, cinema has been targeted by both the government and political organisations. Bollywood helmer Anurag Kashyap’s powerful feature, Black Friday, on the Mumbai riots was not allowed to get out of the cans for years. Documentary movie-maker Anand Patwardhan has had to fight innumerable legal battles to show his works.

Kamal Hassan fell afoul of a virtually unknown political outfit, which sought a ban on his Viswaroopam. It finally opened after a delay of several weeks. More famously, Deepa Mehta’s Water was not allowed to be shot in Varanasi by radical Hindu groups, which felt that the film would denigrate the plight of Vrindavan widows. And decades ago, Krishnaswamy’s wonderful documentary, From Indus Valley to Indira Gandhi, struggled to get a release. His documentary on Operation Blue Star could never see the light of day.

In an atmosphere such as this, it was only natural that exhibitors in Chennai were nervous about releasing Santosh Sivan’s latest, Inam (Ceylon), last week. It talks about the suffering of Tamils in Sri Lanka.

The wounds left by tiny island nation’s three-decade civil strife — which ended in 2009 — are yet to heal. The people of India’s Tamil Nadu share a special affinity with the Sri Lankan Tamils, the language being a strong binding force.

So, when Sivan’s Inam opened last Friday, tens of cops had to be posted in the cinemas to ensure that some group or the other did not cause mayhem. The Tamil Nadu administration need not have worried, for Inam was undoubtedly a pro-Tamil movie.

Sivan’s sympathy lay firmly with the minority group, and Inam looks at the angst and agony of the Tamils on the island as they face the bullets and the bombs of the Sri Lankan army. Yes, Inam may well rake up old wounds or place a road block on the healing process. It has, in any case, not been easy to draw the curtain on the 30-year war that left 40,000 dead in a trail of blood and gore. The casualty may have included many, many more men, women and children. But in warfare, figures are often fudged.

Sivan’s work — which he has himself scripted and photographed with almost divine looking imagery — shot in some of the postcard locales of Kerala, Maharashtra and southern Tamil Nadu (including Rameshwaram), is the heart-rending tale of a young girl, Rajini (played by Sugandha Ram, whom we also saw in Tere Bin Laden), who along with the other inmates of an orphanage in Sri Lanka escapes to India.

But the two people whom she adored — Tsunami Akka (Saritha), who runs the institution, and the teen boy with Down’s syndrome, Nandan (S. Karan) — had to be left behind.

Sivan who spent nine months with Karan, actually suffering from the Syndrome, has done an excellent job of moulding the boy into the role; he is simply delightful to watch, and so are the other performances. Ram infuses pain and poignancy into the character, while Karunas (in a completely different part as Stanley) essays the dilemma of a school teacher, whose pleadings to Tsunami to cross over to India are stubbornly resisted by her with horrible consequences.

Although the plot is wafer thin, Sivan’s script includes an array of anecdotes to keep the movie moving. There are some remarkable sequences with Nandan: look at the way, he plays with a baby tortoise even as guns go rat-a-tat all around him, and his innocent bravado when he hops across a land-mined stretch.

And yet when the bombs actually fall, he covers his head with his shirt hoping that this piece of cloth will shield him, and Sivan’s camera captures the aerial bombing on the orphanage with the frightening intensity it deserves.

If there is a flip side to Inam, it lies in its utter melancholy. Despite, Sivan’s efforts to inject a bit of joy through songs and wit (Stanley’s pet cock is reduced to curry and spice), the film refuses to rise above excruciating sorrow.

Kochadaiiyaan

Rajnikanth starrer, huge-budget Kochadaiiyaan will not open on April 11 as announced some weeks ago. But possibly on May 1, which again is not confirmed. This is nth time that the film’s opening has been postponed.

As I wrote earlier that since April 11 falls bang in the middle of India’s rather difficult and rather controversial parliamentary elections, the producers of Kochadaiiyaan may be uncomfortable with releasing the movie then.

With the nation’s attention focused on the polls, movie producers, distributors and exhibitors could be wary of releasing big budget films, whose box office performance is of life-and-death importance. And Rajnikanth knows this only too well, having burnt his fingers at least on one occasion in the past – when he had to refund money to distributors/exhibitors.

The movie’s co-producer, Murali Manohar, said: “We are looking at a new date. Yes, we’re looking at May 1. Also, the censoring of Kochadaiiyaan in all the various languages is not yet done.”

Yes, this may be one reason. But the real cause is the election, and when it is on, the media has very little time for entertainment.

*Gautaman Bhaskaran has been writing on Indian and world cinema for more than three decades, and may be e-mailed at [email protected]