Astle is thought to have died of dementia brought on by repeatedly heading the ball

Daniel Taylor/The Observer

In the ninth minute of West Bromwich Albion’s game at Hull City the supporters in the away end at the KC Stadium rose to their feet in memory of Jeff Astle, the man they used to call The King. Banners were held up and, knowing how persistent and strong-minded football fans can be when they sense injustice, we can probably expect this to be a regular theme at West Brom’s matches until it shames the people who have ignored this story for too long.

It is 12 years since Astle’s inquest ruled he had died from “industrial disease,” namely dementia brought on by repeatedly heading the ball, and many people might have forgotten by now that the Football Association and Professional Footballers’ Association stated at the time there would be a joint 10-year study to investigate the risks.

Not his family, though. His widow, Laraine, was among West Brom’s travelling fans, like she is most weeks. Two of their three daughters, Dawn and Claire, were there, along with one of his five grandchildren, 16-year-old Matt. In the weeks to follow, the family hope the club will flash messages of support on the electronic scoreboard at The Hawthorns. Yet they know it is complicated.

Astle was 59 when he died, and for part of the previous four years he was in such a bad way he could not even remember which clubs he had played for, never mind the fact he had won five caps with England and played against Brazil in the 1970 World Cup.

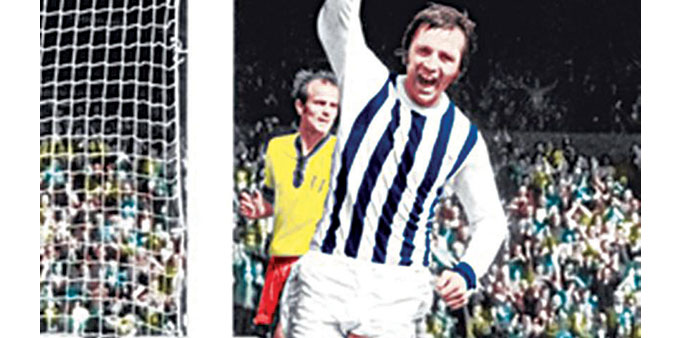

Younger generations will probably remember him for his television appearances with Frank Skinner and David Baddiel on Fantasy Football, closing out the show with a different song each week, and the minute’s silence in the episode after his death. At West Brom, though, he will always be remembered as an icon strong, fearless, ruggedly handsome and, to his cost, exceptional in the air. “Astle is the King” was the graffiti painted on Primrose Bridge in Netherton, in the heart of the Black Country, around the same time he scored the winning goal in the 1968 FA Cup final. Even when the council scrubbed it off, the same words re-appeared within days.

The slogan at Hull on Saturday was “Justice for Jeff” although in fairness to the FA, it is not the current regime that is to blame here. It is their predecessors, going back to the Soho Square era, bearing in mind the promises that were made, after the inquest, when the Astle family were visited at home and assured it would be treated as a priority.

What actually happened was the family received two letters and then never heard from the FA again. The first was from the FA’s solicitors and advised against considering legal action. The next was from a leading FA official asking if the family would like tickets for the next England friendly, with the rider that it would be impossible to squeeze them all in. The offer was for two tickets .

Understandably, there is a certain amount of bitterness. “This was not a Mickey Mouse pathologist,” Dawn says. “It was one of the world’s leading pathologists and his report was that dad’s brain had suffered catastrophic trauma and resembled that of a boxer. It wasn’t a bruised toe or a sore back. My dad is dead, and the FA have ignored it for 12 years. In the meantime, how many former players have lost their lives because of degenerative brain disease and how many are living with its consequences?”

That is the crux of it. When Fabrice Muamba’s heart stopped at White Hart Lane in March 2012 the FA quickly put in place a review of medical practices before teaming up with the British Heart Foundation to make 900 defibrillators available to clubs. Yet there has not been a single piece of data published by the FA on possible links between repeatedly heading the ball and endangering the brain. Instead, it transpires the FA identified some young apprentice footballers to analyse, then closed the file when those players never made the grade. The FA now points out that Fifa has ultimate responsibility for safety in the sport. “It’s a good job the people looking at cancer and Alzheimer’s don’t just give up like that,” is Dawn’s take.

The FA’s new regime, with a strong West Brom theme running through the organisation, do seem to be taking the complaints seriously and the chairman, Greg Dyke, has written to the family this weekend with a long apology. Dyke and his colleagues intend to travel to the Midlands to meet Astle’s relatives and establish what should happen next.

There are wider implications to this story. This newspaper’s information is that Reading’s old-player association has also contacted the relevant authorities over the past few years about the same issue but, again, without getting very far. Astle was far from the only aerial specialist in an era of heavy and often soaked footballs and it is difficult to estimate how many others might have been affected. It is also fairly astounding that the PFA has not taken up the Astlecase more strongly the family say they have not heard from them since the 10-year study was announced.

Research at Turin University, looking at the medical records of 7,000 ex-footballers from 1970 to 2001, has shown the risk of motor neurone disease is six times higher than the norm. Another study by Albert Einstein’s Gruss Magnetic Resonance Research Center in New York found that players in their 30s who headed the ball 885-1,550 times a year had significantly lower water movement in three areas of the brain. The players with more than 1,800 a year tended to do notably worse in memory tests.

A few weeks ago, the death of the 29-year-old Patrick Grange, from the Chicago semi-professional leagues, was posthumously linked to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a brain disease caused by repeated blows to the head. Grange was renowned for his heading ability and the damage was all at the front of his brain. “We can’t say for certain that heading the ball caused his condition,” the neuropathologist Dr Ann McKee told the New York Times. “But it is noteworthy that he was a frequent header of the ball, and he did develop this disease.”