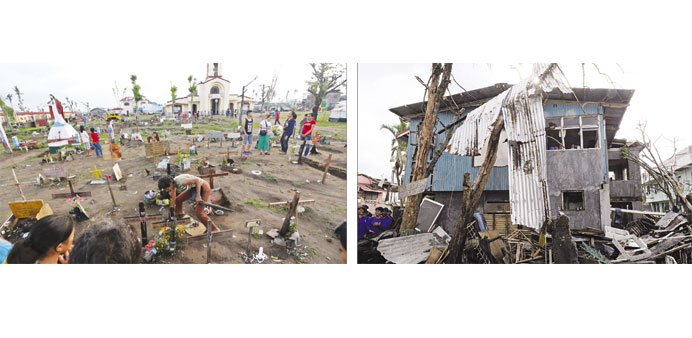

Crescencia Batcha, 58, (centre) cleans the grave of her son and five grandchildren outside a damaged church turned into a mass grave in the super typhoon devastated city of Palo, Leyte province, Philippines. Right: A handout image made available by United Nations, shows buildings destroyed by super typhoon Haiyan in Tacloban City.

DPA/Tanauan

Freddie Boy Dubla sat on a fallen coconut tree along the shore, his gaze fixed on the horizon, unmindful of the sloshing waves that pounded the sand.

The salty sea breeze was refreshing amid the scorching sun and there were a few people swimming, riding with the tide.

“This beautiful sea brought such terrible pain and misery last month,” said the 22-year-old fishermen and part-time rickshaw driver in Leyte province that was devastated by Typhoon Haiyan last month.

Dubla said winds of 300 kilometres per hour caused the sea to rise in a wall of water that slammed into the once-bustling fishing village, killing his parents.

He pointed to a mound of sand with a makeshift wooden cross where he buried his mother, marking the spot where their house used to be just a stone’s throw away from the sea.

She was found four days after Haiyan wreaked havoc on a large part of the eastern and central Philippines on November 8, killing more than 6,000 people and leaving more than 4mn homeless.

A week later, relatives found the body of Dubla’s father and buried it in a mass grave at the town’s plaza.

“We all evacuated the night before but my mother returned without telling us,” Dubla said.

“I think she wanted to get money she left at home. If I had known, I would have gone with her, then maybe she would still be alive — or maybe we would both be dead.” “That’s okay, at least I would have known she didn’t die alone,” he said.

More than a month after the storm, survivors were grieving the loss of their loved ones while trying to pick up their lives, amid the tonnes of debris that have yet to be cleared.

Toppled electricity posts, crushed houses, collapsed buildings, torn metal roofs, and piles of uncollected detritus block some streets, especially in villages. In provincial capital Tacloban, commerce has begun to rebound with stores, hotels, restaurants and even a popular fast-food chain re-opening. Traffic was heavy as backhoes, bulldozers and dump trucks joined the cleanup efforts.

Streets leading to the destroyed public market were crowded as vendors selling goods from mobile phones to slippers, rechargeable lamps, clothes and fruit from roadside stalls.

Electricity was not yet restored to most communities, and activities ground to halt as darkness envelops the city of more than 200,000 inhabitants.

Some piles of debris emit foul smells suggesting decomposing flesh.Leon Angello, a 70-year-old retiree, said the body of a young girl was found just hours earlier from across his home in San Roque village, where he quietly dug out rubbish using a worn-out shovel that he recovered after the typhoon.

“I lost a brother because he went out of the house and was swept away by the raging black water and debris,” he said.

Angello said he and his family climbed to the roof of their house when Haiyan struck and stayed there until the tidal surges subsided.

More than 20 neighbours also sought refuge on their roof.

Outside Angello’s house, Gilberto Catindoy and several other men were clearing the street of debris using shovels, crowbars, machetes and wheel barrows.

Catindoy, a 41-year-old construction worker, said his father died and he lost his house in the typhoon but was thankful that his three children survived.

“It’s time to move on,” he said. “As you can see the cleanup alone will still take some time because of the sheer volume of debris, and heavy machinery cannot enter the alleys so we have to remove all this dirt manually.”

Catindoy was among thousands of survivors hired by the government and international disaster relief agencies to clear roads and streets.

Six weeks after the one of the most powerful typhoons on record, many people like Michelle Maraya were still searching for missing loved ones.

She was among several people who took turns looking at two freshly recovered cadavers in black body bags laid out in the yard of San Joaquin Church, which was turned into a graveyard for hundreds of victims.

They braved the stench of rotting flesh to inspect the cadavers in hopes of finding their loved ones.“I come here every day hoping to be reunited with my two children,” Maraya said.

Her four-year-old daughter and two-year-old son were missing along with her grandmother and an aunt. Eight other relatives died.

“I can still hear them screaming ‘Mama, Mama’ as muddy floodwater swirled inside our house,” Maraya said, angrily wiping away tears from her eyes.

“I don’t think I will be able to find my children anymore.”

“It was like hell when the water came. It became so dark because the water was black and brought garbage with it.”

The 22-year-old sales clerk said she plans to wait outside the church as long as workers are retrieving bodies.

“My father had a dream about my grandmother telling him not to worry about them,” she said.