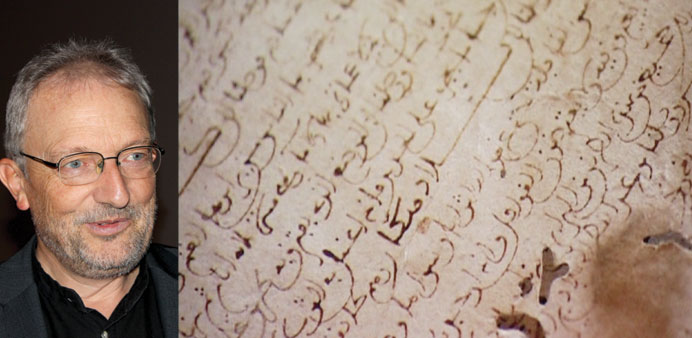

Tim Mackintosh-Smith RIGHT Earliest known MSS of Ibn Battutah’sTravels, possibly in the handwriting of the contemporary scholar and scribe Mohammed Ibn Juzayy al-Kalbi. Photographs by David Gillespie

By Fran Gillespie

One fine morning in 1325 a young man in Morocco set out on a journey ‘as a bird flies the nest’ that was to take him to the farthest reaches of the Islamic world.

An earlier writer had advised Moroccans who wanted to make a name for themselves ‘to head for the land of the east’, and the Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) himself had urged those who wish to acquire knowledge to travel, “even if it takes you as far as China”.

The young man took their advice and wandered across Africa to Egypt. From there he went on to India and China, finally returning to his home some twenty-nine years later, after many adventures, having covered some 75,000 miles.

He narrowly escaped being murdered by bandits on more than one occasion and miraculously avoided succumbing to the many diseases which were rife at the time and for which there was no cure.

Unlike many travellers, he wrote — or rather dictated — an account of his adventures, the Rihlah, or Travels, probably the longest travel book ever to be written.

The name of this courageous and enterprising globe-trotter was Ibn Battutah, and in one of a recent series of lectures held at the Museum of Islamic Art in connection with the current exhibition on Haj, the award-winning writer and traveller Tim Mackintosh-Smith gave a fascinating account of Ibn Battutah’s journey.

Recognised as one of the foremost authorities on the 14th century Moroccan, Mackintosh-Smith, an Arabist who has lived in Yemen for thirty years, where he is popularly known as ‘the sheikh of the Nazarenes’, showed some of his photographs of the places Ibn Battutah had visited.

In his trilogy Travels with a Tangerine, The Hall of a Thousand Columns and Landfalls, an account of his re-creation of Ibn Battutah’s journey published between 2001 and 2005, the author describes his emotions when he visited the actual places Ibn Battutah had seen: public baths near Granada, a mosque in which the Moroccan had worshipped more than six hundred years before, and even the very site in India where Ibn Battutah had witnessed a Hindu widow burn herself to death on her husband’s funeral pyre, with stones still blackened from fire. This eerie experience was “like seeing a ghost,” he remarked in his lecture.

The Islamic world of Ibn Battutah’s day was intricately connected by trade, explained Mackintosh-Smith. Chinese porcelain was exported as far as Zanzibar, and everywhere pearls from the Gulf were in high demand.

Ibn Battutah was not a merchant; instead he carried a non-tangible but immensely valuable export: Islamic jurisprudence. It’s common nowadays for adventurous young travellers to work their way around the world for a year or two.

Ibn Battutah did exactly the same, only for a rather longer period, staying in some cases as long as ten years in one city. He was not a scholar as such, and never claimed to be one, but he studied Islamic law in Damascus and then Mecca (Makkah) before setting out to wander across the world to Delhi, where he was appointed as a qadi, or judge by the sultan, treated with honour and awarded a fat salary. But his fortunes took a turn for the worse when he was sent as an ambassador to China, along with expensive gifts. The boat carrying the gifts was wrecked, and fearing to return to his employer with the bad news Ibn Battutah ended up, after many adventures, in the Maldives.

Mackintosh-Smith described how, after being robbed by bandits in India, Ibn Battutah hid inside a large grain-storage jar in a village, crawling through its narrow entrance.

‘This shows that he was not a fatty!’ remarked the speaker’s guide when they visited the area and saw similar clay storage containers still in use today. In the Maldives, Ibn Battutah noted the pagan custom of sacrificing young virgins in a temple to a demon that came from the sea. Eventually, the demon was routed by a man who volunteered to remain overnight in the temple, reciting from the Holy Qur’an, and so impressing the ruler that he and his people converted to Islam. Recent archaeological discoveries, said Mackintosh-Smith, have uncovered the remains of the temple with a fearsome carving of the demon!

Ibn Battutah, said the speaker, travelled further than any other human until the age of steam, on a sort of ‘exploded Haj’. Fascinated by visiting the places described by the intrepid medieval traveller, he said that perhaps, the strangest and most remarkable experience of them all was actually seeing a wooden musical instrument called a balafon, like a large wooden xylophone with gourds under the keys to resonate the sound, which is reputed to have been constructed more than 800 years ago and which, Ibn Battutah heard played. This instrument, called the Sosso Bala, is kept in a clay hut in the town of Niagassola in Guinea, treasured as sacred and played only once a year.

Mackintosh-Smith endured some unpleasant Ibn Battutah-type adventures himself in making the long and difficult journey to see it. But to a dedicated enthusiast like him, it was well worth it.