|

|

The Indian rupee fell past 64 to the dollar for the first time yesterday and bond yields spiked to a five-year high before the central bank stepped in to support the currency, as Asia’s third-largest economy bore the brunt of the global emerging markets selloff.

Underscoring how hard it is for New Delhi to push through reforms despite the urgency of a deteriorating economic outlook, parliament was adjourned yesterday due to protests by members over a corruption scandal.

India’s notoriously dysfunctional lower house of parliament was due to debate a bill to allow foreign investment in the fledgling private pension industry, a reform seen as key to government efforts to attract investment and narrow the current account deficit, which is exacerbating the currency crisis.

“India’s problems are nowhere near resolution because New Delhi has not done anything - there is no focus on improving productivity, infrastructure or getting FDI (foreign direct investment) back,” said Nomura credit analyst Pradeep Mohinani in Hong Kong.

“It’s all about stemming the flow of currency and that is not the cause of the problem,” he said.

However, India managed to sell $9.3bn worth of government debt limits to foreign institutional investors, although at rock bottom prices, a sign that they hold out hope of improving market conditions.

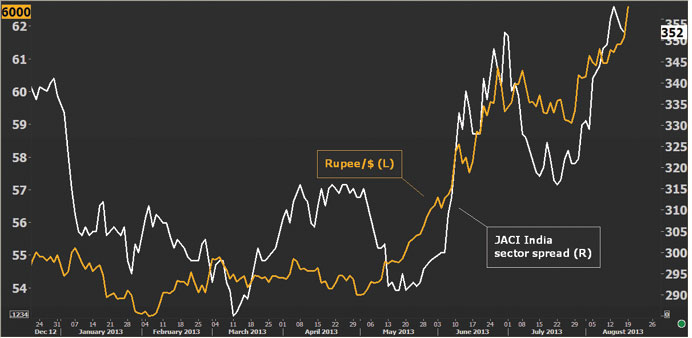

Foreigners have offloaded $10bn in Indian debt since May 22, when the US Federal Reserve first signalled its intention to begin scaling back its quantitative easing. They now hold only 43% of the $30bn limit available to them in Indian government debt.

The rupee slumped as much as 1.6% to an all-time low 64.13 to the dollar, but recovered most of its losses to close at 63.25/26, down about 0.2% on the day, after sustained central bank dollar sales in both the spot and forward markets.

Stocks also recovered after hitting near-year lows, with the main share index closing down 0.34%. Earlier, JPMorgan downgraded Indian equities to “neutral” from “overweight”, citing strains in the balance of payments, while Citi cut its Sensex target to 18,900 from 20,800.

Bond yields spiked to 9.48%, a level not seen since before the Lehman Brothers crisis in 2008, before stability in the rupee helped them recover. Yields closed down 33 basis points on the day, snapping a five-day rise for their biggest single-day fall since May 2010.

A spate of measures by the central bank and government has failed to halt the rupee slide, with liquidity tightening measures aimed at making it harder to short the currency pushing up borrowing rates and battering corporate and investor sentiment.

State-run oil firms, the largest dollar buyers in the forex market, face a deterioration in credit quality if they have to share a higher burden of the country’s fuel subsidies due to rising crude prices and a falling rupee, Moody’s said.

Srei BNP Paribas, an equipment finance company, yesterday raised its benchmark lending rate by 50 basis points to 17.75%, citing a continued rise in borrowing costs. Several Indian banks have also raised lending rates in recent weeks.

“Our rate hike has become imperative to maintain the quality of our portfolio,” D K Vyas, chief executive officer at SREI BNP Paribas, said in a statement.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s weak coalition government, heading into national elections by next May, has been hamstrung from pushing through reforms to attract more long-term capital and close a record-high current account gap that has made India vulnerable to flows away from emerging markets.

Since Singh’s government took office for a second term in 2009, the parliament has been the least productive in nearly three decades, according to PRS Legislative Research.

Instead, India has been limited to piecemeal measures such as Monday’s move to increase the foreign direct investment cap in asset reconstruction companies to 74% from 49%, and a ban on the duty-free import of flat-screen TVs from Aug 26.

Yesterday, the RBI simplified rules for investment in shares and debt of Indian companies listed on local exchanges by non-resident Indians.

The rupee’s plunge also adds to worries about whether Finance Minister P Chidambaram will be able to meet his goal to pare the fiscal deficit to 4.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) this fiscal year.

Rating agency Moody’s said that while the rupee depreciation was a new variable for the economy, the factors underpinning it have been incorporated in its investment grade rating for India.