By Gautaman Bhaskaran

Ritesh Batra’s Dabba or The Lunchbox fascinated me for the sheer novelty of its theme. Imagine weaving a story around the “dabba”, a well-entrenched institution in Mumbai which facilitates hundreds of lunchboxes to be carted from homes or eateries to offices or workplaces.

The transfer, considered foolproof, began to fulfil a necessity in 1880 when what was then called Bombay became a focal point of economic activity. Many, many men from many, many communities came to the city from various parts of India to eke out a living.

Away from homes, wives and mothers, the men found it hard to work and cook their meals. Even when wives and mothers were around, lunch would seldom be ready by the time men left for work. It was then that Mahadeo Havaji Bachche thought of a lunchbox delivery service.

In 1890, he hired 100 men who picked up the “dabba” or lunchbox from a home and delivered it to the office. Soon, the system also included a catering wing, which provided the food when a man lived alone.

Batra’s film revolves around one such loner, a widower working in a government organisation and all set to retire. Every noon, he has a “dabba” delivered to his humble desk, directly beneath a rickety old fan. The food inside the “dabba” prepared by a small restaurant has no great appetising qualities.

And the man, day after day, eats it up as matter of routine, more out of habit, more out of need. But one day, the “dabba” surprises him with real delicious food. The puzzled man laps it up and smacks his lips in sheer joy.

The almost fail-proof “dabba” system in which 5,000 men crisscross Mumbai today picking and delivering lunchboxes for a very nominal fee, had slipped up that particular day. The widower had got the wrong box, lucky though to have got the wrong one.

At the other end, the woman, a young wife worried about her husband’s lack of interest in her and even suspicious of his fidelity, begins – prodded by an elderly neighbour living on top of her flat whom we only hear but never see – an attempt to woo him back through the gastronomic route.

She starts cooking with greater care, and tucks a little note inside the “dabba” – which the widower receives, cherishes and begins to enjoy. He replies, and the exchange of notes becomes a regular affair, the little “dabba” playing cupid between two lonely souls.

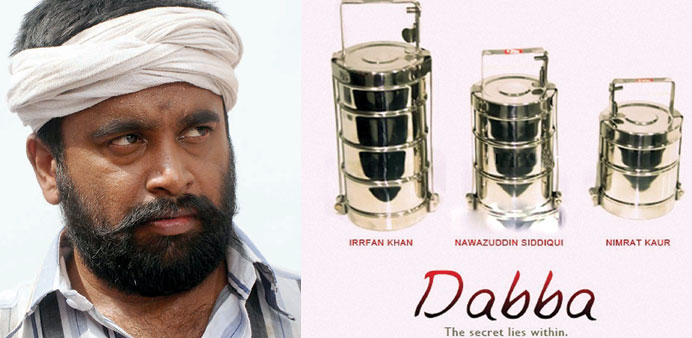

The movie is an elegantly played love story which unfolds against the backdrop of the “dabba” system, whose business model has been taken up for studies outside India. The Lunchbox has a subplot, which is equally interesting. The widower, Saajan Fernandez (Irrfan Khan), is entrusted with the training of Shaikh (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), who will replace the older guy.

Batra cleverly weaves in this story, embellishing it with some witty and some not-so-witty conversations between the two men. As Fernandez begins to experience a sense of satisfaction in the aromatically delightful and deliciously tasty lunch day after day, and to feel the first stirring of love and attention from the unknown woman, Ila (Nimrat Kaur), he softens towards Shaikh.

Fernandez not only teaches Shaikh – after keeping him waiting for days – the ropes of the job he would take up, but also shares the lunch.

While Batra handles the subject with beautiful subtlety, gently nudging both relationships (between Fernandez and Ila, and Shaikh and Fernandez) into a higher plane, he fails to convince why the young woman is tempted to stray. What we get is a mere whiff of her husband’s extra-marital affair that is too by the way to push the plot in the direction the director wants to. This is the weakest link in the film.

The strongest part — apart from Batra’s successful resolve not to let his work sink into a melodramatic mishmash which is too often the case with much of Indian cinema – is the performance. Khan is superb, as always. I had once called him the best of the Khans, and he remains so to my delight. He has an extraordinary range (Paan Singh Tomar, Sahib Bibi Aur Gangster Returns, Life of Pi, A Mighty Heart), and I agree with what one reviewer said: “The star has a chameleon-like presence, and he nails Siddique’s spare melancholy with a deadpan delivery that shifts between droll and downhearted.” However, I would hate to call Khan a star. He is an actor, a great artist. Not a mere star.

Recently at Cannes, when I buttonholed Khan for a short take, he said he had chosen a theme like The Lunchbox “because it was uniquely romantic”. I am always looking to do romantic roles. I want to live my romanticism through movies.” Why not, but in Dabba, Khan’s Fernandez does not get much of chance to woo and win over the girl.

Kutti Puli

Tamil cinema is probably the boldest of all cinemas in India. When its counterparts in Mumbai, Hyderabad and even Kolkata have taken their cameras to cities, telling us urban and urbane tales, Chennai still gives us films which are rooted in villages, capturing the peculiar culture, traditions, mannerisms and even dialects of different regions in Tamil Nadu.

We have movies set in the rural hinterland of Madurai, Tiruchi and Coimbatore among other cities. Tamil cinema does not care to dress up its heroes in Levis and Gucci, neither does it bother to paint the faces of its heroines. These men and women look like the most ordinary of village folks.

In M Muthaiah’s latest offering set in a Tamil Nadu village, Kutti Puli (Cub Tiger), actor Sasikumar – who shot to fame with Subramaniapuram playing a villager – enacts the title role.

Living with his widowed mother, her husband having sacrificed his life for the honour of his village, Kutti Puli is do-gooder who invariably has to resort to violence to save souls. Unsure of his life with enemies abound, he stays away from marriage till he falls in love with Bharathi (Lakshmi Menon).

The film, despite courageously setting its story well outside a city in times like this when most Indian movies make their money in the first weekend multiplex screenings, lacks a certain finesse that can be seen in Mumbai cinema.

Kutti Puli is littered with coincidences, needless songs that disturb the flow and a downright bad performance by Menon. Sasikumar is good, but is overused in the same old beaten role which began with Subramaniapuram – bearded, lungi-clad and tea-sipping epitome of nobility.

Well, he reminds me of M G Ramachandran, who once did tens of movies where he projected himself as the defender of the poor and saviour of women. Of course, MGR, as he was popularly called, never looked shaggy the way Sasikumar appears!

Gautaman Bhaskaran,

who may be e-mailed at [email protected]

has been writing on Indian and world cinema for over three decades and is the author of a biography on Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

Kutti Puli: Rural setting, Dabba: Novel theme.