By Kamran Rehmat/

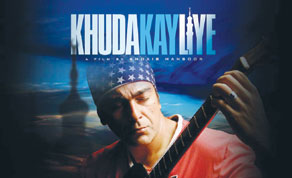

There was genuine hope that the much touted 2007 Pakistani flick Khuda Kay Liye (In The Name of God) could revive the fortunes of a moribund home cinema thanks to the tremendous curiosity around the film and presence of big names, including Indian icon Naseeruddin Shah.

Flick that clicked: Khuda Kay Liye was a massive hit but failed to spur the drive for a cinema in

The theme was set around Muslims facing an identity crisis in a post-Nine Eleven world. It resulted in a grand commercial as well as critical success in

Closer to the Pakistani capital, the residents felt it would serve as a rallying cry for a movie theatre or two in

In fact, much like popular Urdu poet Sahir Ludhianvi’s stirring 1975 Kabhi Kabhi (Once In A While) lyrics in Bollywood legend Amitabh Bacchan’s golden voice it now seems like a gone case:

Magar yeh ho na saka aur ab ye aalam hai

Ke tu nahin, tera gham, teri justajoo bhi nahin

(But it didn’t happen and now life is on verge

That I don’t have you neither sorrow nor hope)

One may be a true blue Islooite - as residents of Islamabad are referred to in popular parlance - but such a huge missing link in the otherwise much fancied “metro” mien of the capital is incomprehensible, not to say, indefensible.

Pithy excuses such as affordability of cable television and cheap copies of latest movies (as well as old) cannot possibly explain away the lack of cinema houses.

At the risk of sounding cliched, there is simply no substitute for the lure and magic of big screen. A mini buff, that is how I have known it since my father took me to watch Ten Commandments in downtown

Even though members of the public, especially in

God knows how starved Islooites are for lack of movie houses, which entails not just feasting one’s eyes on works of art but a jolly good outing with friends and families.

In more tolerant societies, they are also a meeting place for those seeking peace of mind from the cacophony and clutter of strictly business life. The magic of big screen offers them welcome diversion and perhaps, recreation at the same time.

The last time one had occasion to partake the excitement in Islamabad was in 1995, when a cinema of the now-defunct National Film Development Corporation (NAFDEC) screened big budgeted Jo Darr Gaya Woh Marr Gaya (The One Who’s Scared Is A Goner).

In this day and age, Jo Darr Gaya could have had different connotations, for instance, the present and clear danger (read terrorism) would have thrown down the gauntlet to aspiring cinegoers to watch the action in the theatre.

Even so, Jo Darr Gaya was billed as the movie that would revive cinema in

Many in the audience however, appeared to have ventured just to watch how the beautiful Atiqa Odho, who was, by then, a household name thanks to her television prowess, would fare on the big screen.

Small wonder, the hype, in the first place, was owed to Ms Odho’s decision to draw on the fantasy of silver screen, which was projected by many as proof that not everyone in Lollywood - as the Pakistani cinema is referred to after its Lahore-based film industry - was from the “forbidden” place (a metaphor used to describe uncouth women, usually of easy virtue, from the red light zone).

Yet, like the forbidden fruit, Lollywood could do did little to sustain the infusion of new spirit on the back of “respectability”. But the movie houses were packed for as long as the fun lasted, if only to prove that people will take half a chance to go to the theatre if the fare was worthwhile.

What dominates the debate on supposed lack of interest in

While there is no dispute on Lollywood’s abysmal state of affairs for nearly two decades (success of three or four movies in the interim proving little more than an aberration), often forgotten is the fact that cinegoers in

In fact, it would be safe to assume that Pakistani movie buffs - and this is no sweeping generalisation - do not watch the local fare because of the obvious decline in standards. Therefore, the argument that there are no cinemas in

The fact is they would go and watch provided the fare is good. It doesn’t matter if it isn’t Pakistani; they will more than indulge Bollywood (a subject deserving of a separate debate) and

With the man who changed the landscape of the leafy Pakistani capital - Kamran Lashari - as city manager, there was a glimmer of hope the anomaly would be addressed. His exit on political grounds three years ago took care of that, too.

lThe writer is a freelance journalist based in