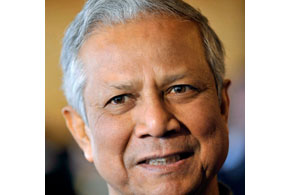

Muhammed Yunus: “The ultimate objective of microfinanciers is to ensure financial inclusion and not making profit”

Bangladesh’s central bank yesterday fired Muhammed Yunus from the celebrated microfinance lender he founded, capping months of political pressure for the Nobel prize winner to quit.

But reflecting a vicious power struggle between the company and the government, Grameen Bank later issued a statement disputing that its talismanic 70-year-old leader had been forced out.

Bangladesh Bank said Yunus had failed to seek its prior approval when he was re-appointed managing director in 2000, violating one of the statutes of the partly state-owned company.

“Professor Muhammed Yunus has been removed from his position as managing director of Grameen Bank,” said the order, which was sent to the bank’s government-appointed chairman Muzammel Huq.

The edict, seen by AFP, added that “his position and tenure as the managing director of the Grameen Bank is illegal”. Huq told AFP that Yunus had been relieved of his duties “with immediate effect”.

However, Grameen, which is 25% state-owned, said it had “complied with the law in respect of appointment of the managing director” and said Yunus “is accordingly continuing in his office”.

The bank pioneered micro-lending in the 1980s in which small amounts of money were leant to mostly poor and rural entrepreneurs, catapulting Yunus to international fame and his Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.

But the country’s only Nobel winner has been under intense pressure from the government to quit his post. In February, Finance Minister A M A Muhith asked him to leave and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has disparaged his work.

Previous attempts to force him from the helm have focused on his age, with the government claiming he had exceeded the age limit for holding a directorship and should retire.

“I do not think there will be any problem with Yunus’s removal — I am sure there will be a smooth transition and the bank will not face any problem,” said Huq, who is openly hostile to Yunus.

The famed economist’s troubles, which have multiplied in recent weeks, are thought to stem from 2007, when he briefly proposed setting up a political party, irking the powerful Hasina and her political allies.

In December, Hasina accused Yunus of treating Grameen Bank as his “personal property” and claimed the group was “sucking blood from the poor”.

Last month, 50 charities and public figures including former Irish president Mary Robinson wrote an open letter calling the campaign against Yunus “politically orchestrated.”

The former academic, who was inspired to start microfinance after observing famines in Bangladesh, has also been summoned to appear in three separate court cases over the last month, all nominally connected to Grameen.

The author of the hit 2007 book “Banker to the Poor: Microlending and the Battle Against World Poverty” also faces a government enquiry into the use of Norwegian aid money.

A documentary by a Norwegian journalist in December alleged Yunus had misused funds in the 1990s, but an investigation in Oslo cleared him of any wrong-doing.

The US ambassador in Dhaka, James Moriarty, has pressed the government to treat Yunus with respect and the embassy said yesterday it was “deeply troubled” by the latest development.

“We hope a mutually satisfying compromise can be achieved that will ensure Grameen Bank’s autonomy and effectiveness,” a statement said.

Yunus’s problems come at a time when the microfinance industry he pioneered is under threat.

In India, the $7bn sector was until recently hailed as a saviour of the country’s poor for providing loans averaging $250 to millions of borrowers outside the mainstream banking sector.

But surging profits, charges of arm-twisting debt collectors and annual interest rates of over 30% have led to mounting controversy and a backlash from lawmakers and

borrowers.

Many commercial banks have restricted lending to microfinance institutions and the sector faces new government regulations to cap interest rates and loans.

Last month, Yunus himself hit out at “loan sharks” masquerading as microfinance

institutions.

“When they start looking at profit they become loan-sharks,” he told a conference in Mumbai. “The ultimate objective of microfinanciers is to ensure financial inclusion and not making profit.” AFP