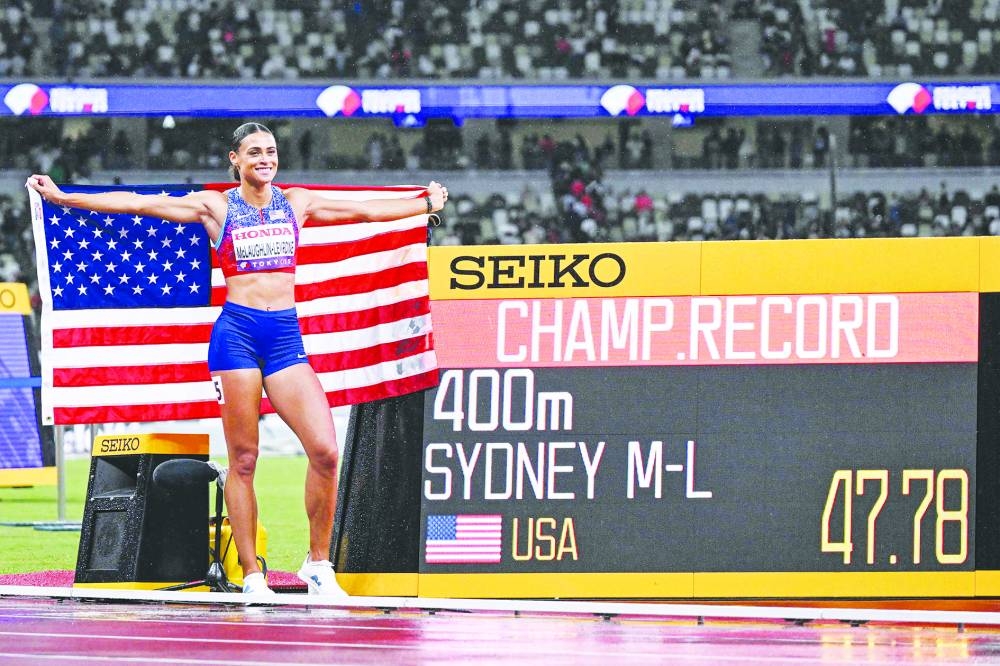

Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone brought the house down yesterday by coming within a whisker of breaking the four-decade-old women’s 400 metres world record while Botswana’s Busang Collen Kebinatshipi impressively won the men’s one-lap title.McLaughlin-Levrone ran through the rain to take gold and post the second fastest time in history of 47.78sec at the Tokyo National Stadium. It will surely only be a matter of time before the 400m hurdles world recordholder breaks the mark of 47.60 set by East Germany’s Marita Koch in 1985, which has long had question marks hanging over it.McLaughlin-Levrone’s decision to switch from the hurdles to the flat this season paid off handsomely.It was the same stadium where the 26-year-old American won her first 400m hurdles gold, but that was in front of empty stands due to the Covid restrictions at the Tokyo Olympics. This time she was able to rush over, stand on her toes and kiss her husband, Andre Levrone Junior, among the spectators.“You know at the end of the day, this wasn’t my title to hold on to, it was mine to gain,” she said. “Bobby (Kersee her coach) uses boxing terms all the time. He said you got to go out there and take the belt It’s not yours and you got to go earn it.”Botswana came into the men’s 400m final never having won a medal in the event in the championships – they left with two. The largely unknown Busang Collen Kebinatshipi took gold, in 43.53sec, the fastest time in the world this year.**media[358673]**His teammate Bayapo Ndori added bronze. “This is my first title and it feels crazy,” said Kebinatshipi. “In the final, I had no fear. I wanted to go all out and see where I could go.”Trinidad, like Botswana, also took away two medals. Seasoned campaigner Jereem Richards won silver in the 400m – if he had had another 10 metres it would have been gold, so fast was he finishing – and 2012 Olympic champion Keshorn Walcott rolled back the years to win the javelin world title.“When we spoke about this before the competition it looked like a joke,” said Richards of their double haul. “Now it’s a reality.”All good things have to come to an end and such was the case for entertaining Venezuelan triple jump icon Yulimar Rojas. The 29-year-old’s record run of four successive world outdoor golds was ended by Leyanis Perez Hernandez, who won Cuba’s first gold in the women’s triple jump since Yargelis Savigne collected the second of her world titles in 2009.“I’m proud of myself,” said Rojas, who missed the 2024 Paris Olympics after injuring her Achilles tendon. “I had two very tough years but this is the life of an athlete. You have to go through hard times and show you can come back. That’s what I did and it means a lot.”Kenya’s women have dominated the middle distance and longer running events so far, with their bitter rivals Ethiopia failing to land a blow – and their dominance unlikely to be halted in the women’s 5,000.Today’s final will be a clash between world record holder Beatrice Chebet and defending champion Faith Kipyegon.Both sailed through qualifying and adding spice to the battle for supremacy as both women are going for doubles, Chebet to add to her 10,000m gold and Kipyegon the 1,500m title.There is, though, one middle distance event where Kenya does not rule – the women’s 800m. Britain’s Olympic champion Keely Hodgkinson, who was laid low for almost a year by hamstring problems, cruised through her heat.The 23-year-old, who posted the fastest time of the year, 1min 54.74sec, on her return to action in the Silesia Diamond League meeting last month, said Olympic gold would take a backseat if she wins on Sunday. “It would mean more than last year,” she said.

Tuesday, February 10, 2026

|

Daily Newspaper published by GPPC Doha, Qatar.