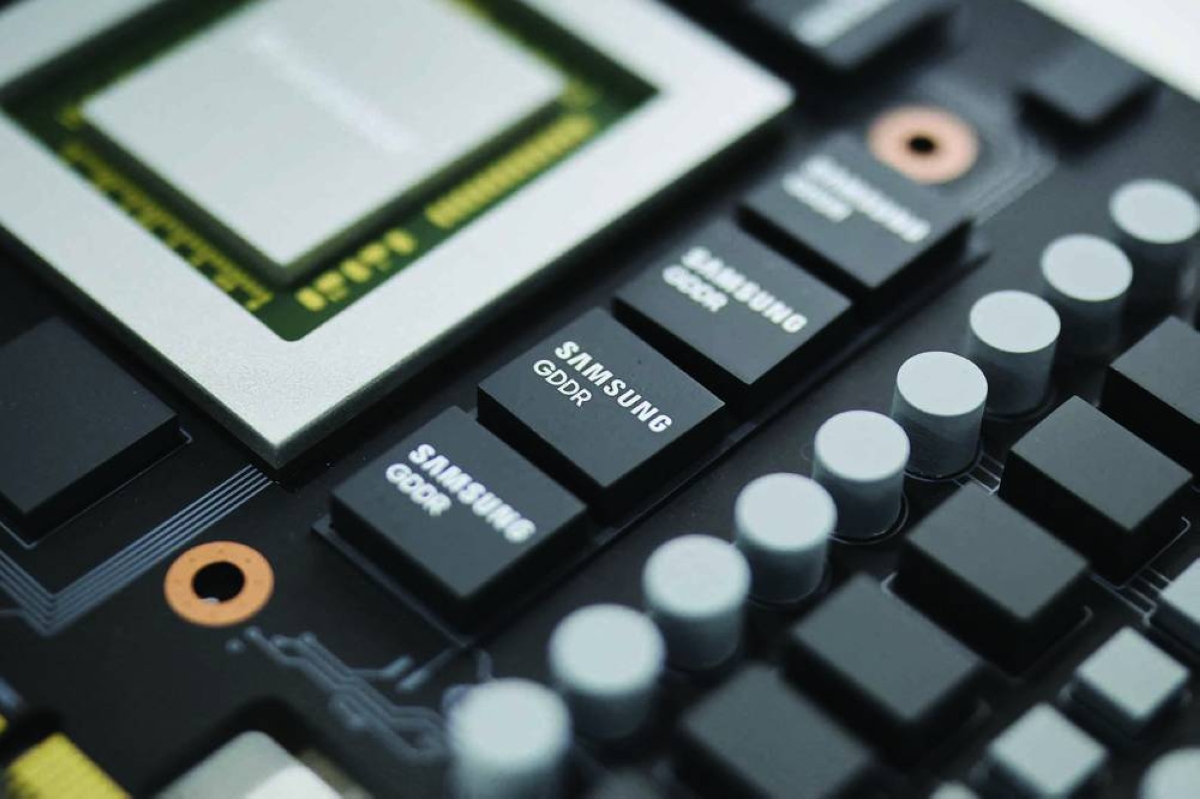

The short history of the self-driving car industry has been littered with expensive failures and endless delays, but tech suppliers, chipmakers including Nvidia and some automakers are betting on AI and a web of partnerships to spark new progress.Many interested automakers, however, still have major questions. Apart from concerns about high costs and scalability, they want to know if there is enough customer demand to make money out of an expensive wager.Vehicles that drive themselves would change the transportation landscape, but making such a technology safe for public roads has been harder and much more expensive than expected.While a few companies such as Alphabet's Waymo and Tesla have decided to do it themselves, veterans such as General Motors and Ford Motor have abandoned their in-house efforts for fully autonomous vehicles. At the CES show in Las Vegas this week, AWS and German supplier Aumovio announced a deal to support the commercial rollout of self-driving vehicles, while autonomous truck firm Kodiak AI and Bosch said they have partnered to ramp up manufacturing of autonomous trucking hardware and sensors. AI chip company Nvidia rolled out its next-generation platform which will be used in a robotaxi alliance announced by Lucid Group, Nuro and Uber. Powered by Nvidia's chips, Mercedes-Benz said this week it will launch a new advanced driver-assistance system in the United States later this year that lets its vehicles operate autonomously on city streets under driver supervision.The propulsive force behind self-driving technology - artificial intelligence - is also coming into its own as a development tool, offering hopes of mitigating high costs.AI and generative AI are acting as a "big accelerant" for the industry "because it actually allows... a significant amount of development and validation with significantly fewer resources," said Ozgur Tohumcu, general manager for automotive and manufacturing at Amazon's cloud unit Amazon Web Services. Western automakers are also under pressure to keep up with China's push to lead the development and adoption of autonomous driving. Just last month, the Chinese government approved two cars with Level 3 autonomous capabilities, which allows hands-off driving. The auto industry has defined five levels of autonomous driving, from cruise control at Level 1 to fully self-driving, without a human minder needed, at Level 5.Still, Jochen Hanebeck, CEO of German chipmaker Infineon , cautioned against "market fantasy" that somehow fully self-driving cars could become commonplace within a few years.Rather than risk fresh investments in fully self-driving, major automakers want revenue-generating driver assistance technology, known as Level 2, that is already available but requires drivers to pay constant attention, he said."I don't see, really now, a tsunami flowing towards Level 5," Hanebeck said. In recent months there has been a flurry of small robotaxi deployments announced in China, the United States, Europe and the Middle East, but Jeremy McClain, head of system and software at Aumovio's autonomous mobility unit, said that expanding the areas they cover requires more data, fleets and logistics, "which is costly and expensive."The self-driving car industry is long on hype. Tesla CEO Elon Musk promised in 2019 that a year later the electric vehicle maker would have a million self-driving cars on the road. But Tesla launched a small robotaxi trial service only last year, six years after Musk's bold prediction.The problem was that cars face billions of potential unexpected incidents, or "edge cases," that can easily fool self-driving vehicles. One example often touted by experts is that if a human driver sees a ball rolling into the street, they automatically slow because it might be pursued by a child - but a self-driving car will react only when it sees the child. After the first self-driving bubble burst, major automakers including Ford and GM abandoned money-losing autonomous vehicle units. The demise of GM's Cruise was accelerated by an incident in which it struck and dragged a pedestrian 20 feet (6 meters).But Ali Kani, general manager of the automotive team at Nvidia, said AI has enabled advances to address key weaknesses in self-driving technology."There's some foundational pieces of technology that make us feel like we're there," Kani said.Morgan Stanley analysts in a note on CES said that while Nvidia's new Alpamayo platform for self-driving would give legacy carmakers a leg up and help them pressure Tesla, the EV maker was years ahead. That said, many in the industry see Nvidia, whose platform is open-source, as a convenient place for Tesla rivals to gather."In one way, you could almost see Apple and Android playing out," said Russell Ong, former product lead at self-driving vehicle maker Zoox, referring to Tesla's proprietary system versus Nvidia’s decision to release Alpamayo as an open-source model.