Since generative artificial intelligence began to make headlines in 2022, investors have poured money into Nvidia Corp, convinced that its leading position in AI hardware will deliver riches.

The bet has paid off handsomely. The company reached a valuation of $5tn in late October and is on course to report more net income this year than its two main rivals will chalk up in sales, combined. A flurry of multi-billion-dollar data centre investments in recent months suggests that, if anything, the AI gold rush is still accelerating.

But a massive run-up in stock prices — and the questionable nature of some AI deals — has left some in the industry wondering if it’s all happening too fast. There are concerns that, when the dust settles, there won’t be enough profitable work to justify the massive outlays on AI infrastructure.

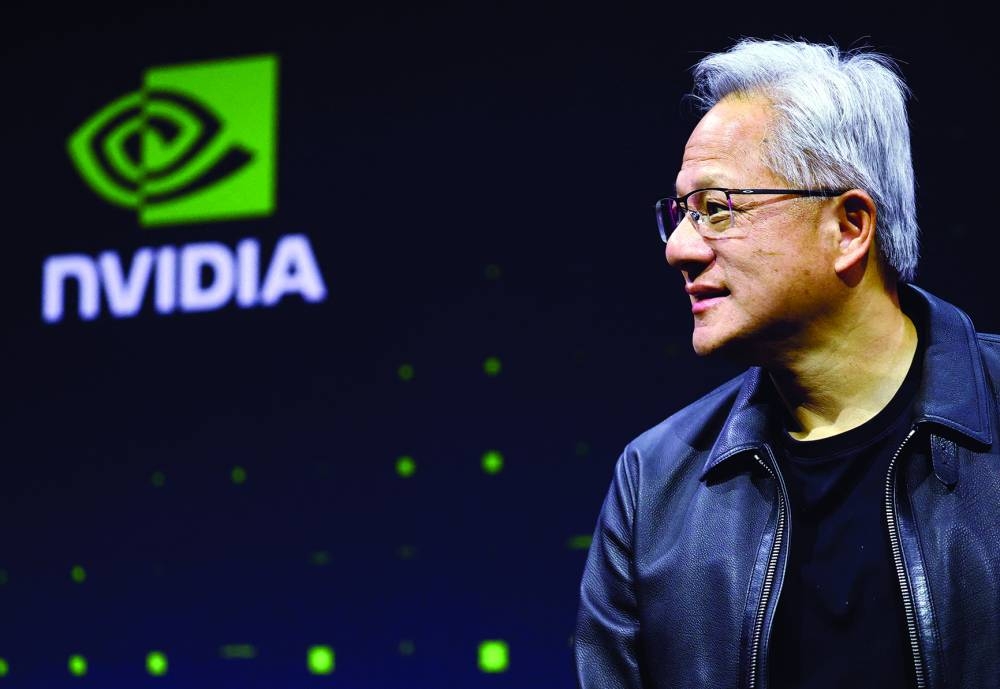

Nvidia Chief Executive Officer Jensen Huang has rejected concerns that AI is a bubble that will eventually pop. He’s been touring the world in an effort to win over politicians still sceptical of the technology and lobby for the removal of national security restrictions that prevent Nvidia from selling its most powerful and profitable chips in China — the world’s biggest market for semiconductors.

What are Nvidia’s most popular AI chips?

Nvidia’s most lucrative product right now is the Blackwell range of AI accelerators, named after mathematician David Blackwell, the first Black scholar inducted into the National Academy of Sciences. Like the Hopper range that preceded it, Blackwell was adapted from the graphics processing units used for video games. It comes in various forms, ranging from individual “cards” to massive computer arrays.

Both Hopper and Blackwell include technology that turns clusters of computers equipped with Nvidia chips into single units that can process vast volumes of data and make computations at high speeds. This makes them a perfect fit for the power-hungry task of training the neural networks that underpin the latest generation of AI products. Nvidia has fine-tuned its offering to better handle inference, in which an AI platform identifies objects through their common characteristics — differentiating, for example, between a cat and a dog. Demand for this capability is soaring as more people turn to AI to help with a growing array of tasks.

The Santa Clara, California-based company is offering Blackwell in a variety of options, including as part of the GB200 superchip, which combines two Blackwell GPUs with one Grace central processing unit — the heart of a computer that executes program instructions. (The Grace CPU is also named for Grace Hopper.)

What’s so special about Nvidia’s AI chips?

Nvidia, founded in 1993, was already the king of GPUs, the components that generate the images you see on a computer screen. The most powerful of those are built with thousands of processing cores that perform multiple simultaneous threads of computation. This allows them to produce the complex 3D renderings like shadows and reflections that are a feature of fast-paced video games.

Nvidia’s engineers realised in the early 2000s that they could retool these components for other applications. AI researchers, meanwhile, discovered that their work could finally be made practical by using this type of chip.

So-called generative AI platforms learn tasks such as translating text, summarising reports and synthesising images by ingesting vast quantities of pre-existing material. The more they absorb, the better they perform. They develop through trial and error, making billions of attempts to achieve proficiency and sucking up huge amounts of computing power along the way.

Blackwell delivers 2.5 times Hopper’s performance in training AI, according to Nvidia. The new design has so many transistors — the tiny switches that give semiconductors their ability to process information — that it can’t be produced conventionally as a single unit. It’s actually two chips married to one other through a connection that ensures they act seamlessly as one, according to the company.

For customers racing to train their AI systems to perform new tasks, the performance edge offered by Hopper and Blackwell chips is critical. The components are seen as so key to developing AI that the US government has restricted their sale to its strategic rival China.

What are Nvidia’s competitors doing?

Advanced Micro Devices Inc and Intel Corp are striving to match the capabilities of Nvidia’s AI products. But for now it controls about 90% of the market for data centre GPUs, according to market research firm IDC. The lack of credible competition is a worry for Nvidia’s cloud computing customers Amazon.com Inc, Alphabet Inc’s Google and Microsoft Corp, which are responding by trying to develop chips in-house for their cloud computing operations.

At the Computex trade show in Taiwan in May, Nvidia signalled a willingness to accommodate the moves by some customers to produce their own key components, with Huang announcing that the company’s NVLink server backbone — a set of components that act as a high-speed link between the main chips in a computer — will be opened up to products from other companies. Previously, that technology had been reserved solely for Nvidia’s own processors and accelerator chips.

AMD, Nvidia’s closest rival in graphics chips, signed a deal to supply ChatGPT maker OpenAI Inc with a huge array of its new AI accelerators. That agreement, and a deal with Oracle Corp, suggested AMD has gained some credibility as an alternative to Nvidia.

How does Nvidia stay ahead of its competitors?

Nvidia has updated its offerings, including software to support the hardware, at a pace that no other firm has been able to match. The company has also devised cluster systems that help customers to buy chips in bulk and deploy them quickly. Huang keeps up a frantic pace of appearances at tech shows and company events all over the world to tout new offerings and tie-ups.

Nvidia has committed to annual introductions of new flagship products for years to come, reflecting what Huang says is an unprecedented commitment to advancing innovation in the industry. Such pledges serve as a warning to rivals that they are trying to catch a moving train.

How is AI chip demand holding up?

Huang and his team have said repeatedly that the company has more orders than it can fill, even for older models. In late October, at a company conference in Washington DC, Nvidia projected revenue of about $500bn from its data centre unit over the next five quarters. That forced even the most optimistic analysts to raise their estimates and helped to add $400bn to Nvidia’s market value in one week.

Microsoft, Amazon, Meta Platforms Inc and Google have announced plans to spend hundreds of billions of dollars collectively on AI and the data centres to support it. OpenAI has been making serial purchases of computing power to be deployed in the near future. The great AI build continues apace in the face of concerns that underlying use-cases for the technology may not yet justify such gargantuan investments.

How do AMD and Intel compare with Nvidia in AI chips?

AMD, the second-largest maker of computer graphics chips, unveiled a version of its Instinct line in 2023 aimed at the market that Nvidia dominates. A new, ramped up version, MI450, will debut next year and has already been included in the plans of Oracle and OpenAI. Chief Executive Officer Lisa Su, typically one of the technology world’s less effusive leaders, has estimated the market for her company’s AI chips will be worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Intel, the dominant provider of computer processors for the majority of Nvidia’s existence, is rebooting its attempt to get into the AI accelerator market. A new management team is focusing on raising cash to bolster its balance sheet, and Intel doesn’t have a directly competitive product scheduled to appear for at least a year. In the meantime, it’s actually teaming up with Nvidia, acknowledging that partnering with the new industry leader makes more sense than trying to fight it. New PC and data-centre chips that are a combination of Intel and Nvidia products will appear soon, opening previously closed markets to Nvidia products.

Geopolitics

The US and Chinese governments have done a lot more than Nvidia’s competitors to make a dent in the company’s sales. In April, Nvidia said it was taking a $5.5bn inventory writedown caused by a US ban on the supply of its H20 chip to companies in China. The H20 is a chip with pared-back capabilities designed to get it past earlier US restrictions on China sales. The US later gave Nvidia a green light to resume H20 sales, but then the government in Beijing retaliated by telling Chinese companies to avoid Nvidia’s offerings.

Huang has travelled to Washington to try to convince President Donald Trump that doing more business with China is good for US national security. If US companies don’t provide the building blocks of AI, he argues, other nations — most notably China in the form of Huawei Technologies Co — will step in and that will threaten America’s technological leadership.

That point of view has gained some traction among politicians in Washington, and the president has name-checked Nvidia’s products and talked about discussing them with his Chinese counterparts. But so far there’s been no concrete agreement that would allow Nvidia to sell to China again.

The bet has paid off handsomely. The company reached a valuation of $5tn in late October and is on course to report more net income this year than its two main rivals will chalk up in sales, combined. A flurry of multi-billion-dollar data centre investments in recent months suggests that, if anything, the AI gold rush is still accelerating.

But a massive run-up in stock prices — and the questionable nature of some AI deals — has left some in the industry wondering if it’s all happening too fast. There are concerns that, when the dust settles, there won’t be enough profitable work to justify the massive outlays on AI infrastructure.

Nvidia Chief Executive Officer Jensen Huang has rejected concerns that AI is a bubble that will eventually pop. He’s been touring the world in an effort to win over politicians still sceptical of the technology and lobby for the removal of national security restrictions that prevent Nvidia from selling its most powerful and profitable chips in China — the world’s biggest market for semiconductors.

What are Nvidia’s most popular AI chips?

Nvidia’s most lucrative product right now is the Blackwell range of AI accelerators, named after mathematician David Blackwell, the first Black scholar inducted into the National Academy of Sciences. Like the Hopper range that preceded it, Blackwell was adapted from the graphics processing units used for video games. It comes in various forms, ranging from individual “cards” to massive computer arrays.

Both Hopper and Blackwell include technology that turns clusters of computers equipped with Nvidia chips into single units that can process vast volumes of data and make computations at high speeds. This makes them a perfect fit for the power-hungry task of training the neural networks that underpin the latest generation of AI products. Nvidia has fine-tuned its offering to better handle inference, in which an AI platform identifies objects through their common characteristics — differentiating, for example, between a cat and a dog. Demand for this capability is soaring as more people turn to AI to help with a growing array of tasks.

The Santa Clara, California-based company is offering Blackwell in a variety of options, including as part of the GB200 superchip, which combines two Blackwell GPUs with one Grace central processing unit — the heart of a computer that executes program instructions. (The Grace CPU is also named for Grace Hopper.)

What’s so special about Nvidia’s AI chips?

Nvidia, founded in 1993, was already the king of GPUs, the components that generate the images you see on a computer screen. The most powerful of those are built with thousands of processing cores that perform multiple simultaneous threads of computation. This allows them to produce the complex 3D renderings like shadows and reflections that are a feature of fast-paced video games.

Nvidia’s engineers realised in the early 2000s that they could retool these components for other applications. AI researchers, meanwhile, discovered that their work could finally be made practical by using this type of chip.

So-called generative AI platforms learn tasks such as translating text, summarising reports and synthesising images by ingesting vast quantities of pre-existing material. The more they absorb, the better they perform. They develop through trial and error, making billions of attempts to achieve proficiency and sucking up huge amounts of computing power along the way.

Blackwell delivers 2.5 times Hopper’s performance in training AI, according to Nvidia. The new design has so many transistors — the tiny switches that give semiconductors their ability to process information — that it can’t be produced conventionally as a single unit. It’s actually two chips married to one other through a connection that ensures they act seamlessly as one, according to the company.

For customers racing to train their AI systems to perform new tasks, the performance edge offered by Hopper and Blackwell chips is critical. The components are seen as so key to developing AI that the US government has restricted their sale to its strategic rival China.

What are Nvidia’s competitors doing?

Advanced Micro Devices Inc and Intel Corp are striving to match the capabilities of Nvidia’s AI products. But for now it controls about 90% of the market for data centre GPUs, according to market research firm IDC. The lack of credible competition is a worry for Nvidia’s cloud computing customers Amazon.com Inc, Alphabet Inc’s Google and Microsoft Corp, which are responding by trying to develop chips in-house for their cloud computing operations.

At the Computex trade show in Taiwan in May, Nvidia signalled a willingness to accommodate the moves by some customers to produce their own key components, with Huang announcing that the company’s NVLink server backbone — a set of components that act as a high-speed link between the main chips in a computer — will be opened up to products from other companies. Previously, that technology had been reserved solely for Nvidia’s own processors and accelerator chips.

AMD, Nvidia’s closest rival in graphics chips, signed a deal to supply ChatGPT maker OpenAI Inc with a huge array of its new AI accelerators. That agreement, and a deal with Oracle Corp, suggested AMD has gained some credibility as an alternative to Nvidia.

How does Nvidia stay ahead of its competitors?

Nvidia has updated its offerings, including software to support the hardware, at a pace that no other firm has been able to match. The company has also devised cluster systems that help customers to buy chips in bulk and deploy them quickly. Huang keeps up a frantic pace of appearances at tech shows and company events all over the world to tout new offerings and tie-ups.

Nvidia has committed to annual introductions of new flagship products for years to come, reflecting what Huang says is an unprecedented commitment to advancing innovation in the industry. Such pledges serve as a warning to rivals that they are trying to catch a moving train.

How is AI chip demand holding up?

Huang and his team have said repeatedly that the company has more orders than it can fill, even for older models. In late October, at a company conference in Washington DC, Nvidia projected revenue of about $500bn from its data centre unit over the next five quarters. That forced even the most optimistic analysts to raise their estimates and helped to add $400bn to Nvidia’s market value in one week.

Microsoft, Amazon, Meta Platforms Inc and Google have announced plans to spend hundreds of billions of dollars collectively on AI and the data centres to support it. OpenAI has been making serial purchases of computing power to be deployed in the near future. The great AI build continues apace in the face of concerns that underlying use-cases for the technology may not yet justify such gargantuan investments.

How do AMD and Intel compare with Nvidia in AI chips?

AMD, the second-largest maker of computer graphics chips, unveiled a version of its Instinct line in 2023 aimed at the market that Nvidia dominates. A new, ramped up version, MI450, will debut next year and has already been included in the plans of Oracle and OpenAI. Chief Executive Officer Lisa Su, typically one of the technology world’s less effusive leaders, has estimated the market for her company’s AI chips will be worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Intel, the dominant provider of computer processors for the majority of Nvidia’s existence, is rebooting its attempt to get into the AI accelerator market. A new management team is focusing on raising cash to bolster its balance sheet, and Intel doesn’t have a directly competitive product scheduled to appear for at least a year. In the meantime, it’s actually teaming up with Nvidia, acknowledging that partnering with the new industry leader makes more sense than trying to fight it. New PC and data-centre chips that are a combination of Intel and Nvidia products will appear soon, opening previously closed markets to Nvidia products.

Geopolitics

The US and Chinese governments have done a lot more than Nvidia’s competitors to make a dent in the company’s sales. In April, Nvidia said it was taking a $5.5bn inventory writedown caused by a US ban on the supply of its H20 chip to companies in China. The H20 is a chip with pared-back capabilities designed to get it past earlier US restrictions on China sales. The US later gave Nvidia a green light to resume H20 sales, but then the government in Beijing retaliated by telling Chinese companies to avoid Nvidia’s offerings.

Huang has travelled to Washington to try to convince President Donald Trump that doing more business with China is good for US national security. If US companies don’t provide the building blocks of AI, he argues, other nations — most notably China in the form of Huawei Technologies Co — will step in and that will threaten America’s technological leadership.

That point of view has gained some traction among politicians in Washington, and the president has name-checked Nvidia’s products and talked about discussing them with his Chinese counterparts. But so far there’s been no concrete agreement that would allow Nvidia to sell to China again.