The first time Revelstoke Capital Partners asked investors if it could hold on to Fast Pace Health for longer than usual, they obliged. It was 2020, and a global pandemic had markets on edge.

So Revelstoke put a piece of the medical clinic chain into a new fund and found fresh investors to replace those who wanted their money back. The move allowed some backers to retrieve their cash without forcing the private equity firm to sell at an unattractive price.

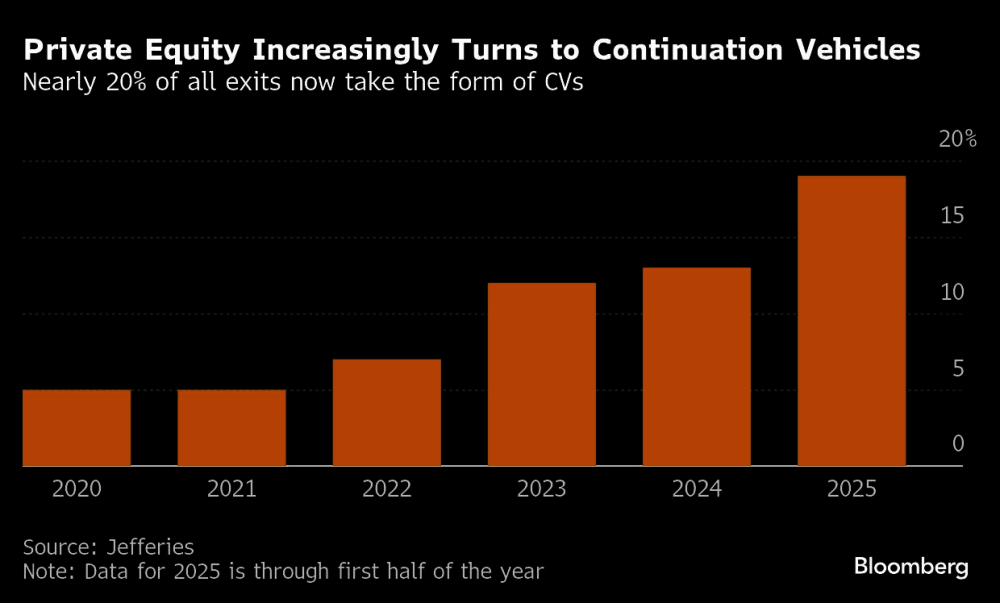

Structures like this, often called continuation vehicles, or CVs, have since exploded in popularity as private equity firms limp through a dealmaking drought. Their growth is such that some are now creating CVs of CVs — or CV-squareds, as they’re known.

In the case of Revelstoke, backers pushed against a more recent attempt to extend the Denver-based firm’s ownership of Fast Pace Health through a new continuation fund, according to people familiar with the matter. The plans were eventually shelved, said the people, who asked not to be identified as the deliberations were private.

The stymied deal highlights a tension building between private equity firms and their investors. Buyout shops have a huge backlog of companies to dispose of as elevated interest rates keep a lid on acquisitions. Investors, meanwhile, are growing impatient. And there are no easy solutions.

“I don’t think this is the norm,” Harold Hope, global head of private market secondaries at Goldman Sachs Group, said in an interview. “I can’t think of us having gone into a CV deal where we thought the exit was going to be another CV deal.”

Revelstoke declined to comment.

Other managers have found success. Accel-KKR Co extended its ownership of isolved, a human-resources software firm, raising $1.9bn for a second continuation vehicle. CapVest, meanwhile, is attempting to move Curium Pharma to a second continuation vehicle, and PAI Partners is looking to do the same with ice cream producer Froneri, the people said.

CapVest didn’t respond to a request for comment. PAI declined to comment.

Goldman has emerged as the lead investor in Accel-KKR’s CV-squared. It is also a lead investor in PAI’s CV-squared transactions, according to people with knowledge of the deals.

Hope declined to comment on the transactions. But in general, he said some companies benefit from remaining private and being held for longer.

Private equity firms have been under pressure to return money to their investors as a dealmaking slump drags on for a third year. Distributions as a percentage of fund values tumbled to 7% as of the first quarter of this year, compared to around 25% between 2015 and 2019, according to Abdulla Zaid of MSCI Inc.

The number of repeat continuation vehicles is still relatively small, Adam Johnston, partner and a member of Stepstone Group’s private equity team, said in an interview.

Many repeat CVs are cases where a bunch of assets were previously rolled into a new fund, and the sponsor is now pursuing a second or third continuation vehicle for just one of the remaining assets, according to market participants.

Buyout firms often think “there’s still meat on the bone and they want to continue holding the companies,” he said. In other cases, returning or lead investors want cash and push the firm to raise money for a continuation vehicle, he added.

It’s possible that continuation funds are the best use of money for some investors at the moment. An Evercore Inc report shows that by at least one measure, single-asset CVs outperformed buyouts in recent years. They also tend to carry lower management fees than traditional private equity vehicles.

Accel-KKR’s investment in isolved, which the firm acquired in 2011, has generated a 19.2 times gross multiple on investment, according to people with knowledge of the matter. It pitched another continuation fund for isolved because the company has more room for growth, the people said.

Still, CV-squared deals face unusual amounts of investor scrutiny because sales or public offerings are preferred.

“My preferred exit path in every case is a sale to a strategic buyer who can overpay because they’re going to get the benefit of various synergies,” said Amyn Hassanally, global head of private equity secondaries at Pantheon.

One problem with CV-squared deals is an inherent conflict of interest between investors and private equity firms, Hassanally said. The process allows private equity firms to renegotiate their fees and interest in the assets as they move them from one continuation fund to another.

Buyout firms should show they have run “a full and fair process” to find accurate prices for their assets even if they’re being rolled into a new continuation vehicle, he said.

Naturally, some buyers are sceptical, avoiding CV-squared deals despite the pitches of private equity firms.

“Our view is that we find better risk-return opportunities in the first chapter of a CV than a second,” said Stepstone’s Johnston.