President Donald Trump is betting that tariffs on imports of vehicles and automotive parts will bring more manufacturing to US shores.

Realising that ambition rests on a major overhaul of the globally integrated supply chains the auto industry has spent decades fine-tuning. Cars aren’t single-origin products like coffee. They’re made up of tens of thousands of components — from transmissions to alternators to individual springs — that are sourced from all over the world.

Shifting production of more of those parts to the US would be an expensive transition for carmakers. American consumers are likely to feel the pain too, as tariffs are widely expected to push up vehicle prices by thousands of dollars.

What US tariffs does the auto industry face?

A 25% levy on all foreign-made vehicles brought into the US kicked in on April 3. There’s an exemption for cars that comply with the terms of a free trade agreement between the US, Mexico and Canada, known as the USMCA: The import tax will only be charged on the share of non-US content in those vehicles.

Auto parts also faced a 25% duty, but after industry pushback, Trump modified the arrangement so carmakers that produce and sell completed automobiles in the US can claim an offset worth up to 3.75% of the value of US-made vehicles. This is set to fall to a maximum of 2.5% after one year, and then be eliminated the following year, a bid to motivate domestic manufacturing. Components that comply with the USMCA will be spared from the 25% levy.

Trump granted the auto sector further relief by exempting it from separate import taxes on steel and aluminium products that went into effect in March, in an effort to avoid multiple tariffs stacking on top of each other.

How have Trump’s auto tariffs evolved?

The president had previously said that the auto tariffs were “permanent.” But they’ve been subject to some alterations since they were first announced, with reductions for some of the biggest exporters of vehicles to the US.

Trade agreements the US reached with the European Union, Japan and South Korea lowered tariffs on vehicles imported from those trade partners to 15% from 25% previously. A separate deal with the UK cut the duty to just 10%, but only for the first 100,000 UK cars sold in the US. Every vehicle above that faces a 27.5% tariff.

While that’s good news for the likes of South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Co and Japan’s Toyota Motor Corp, the moves have stirred some discontent in Detroit. The American Automotive Policy Council, which lobbies for Ford Motor Co, General Motors Co and Stellantis NV, decried the US-Japan pact as a “bad deal” because it lowered duties on imported Japanese vehicles with “virtually” no US parts content.

Jim Farley, Ford’s chief executive officer, took the pushback a step further. Lowering tariffs on Japanese imports, he says, puts Ford’s US-made vehicles at a major cost disadvantage, to the tune of about $5,000 when comparing a Ford Escape small SUV made in Kentucky with a competing Toyota Rav4 built in Japan. (Toyota also builds Rav4s for US consumption in Ontario, Canada and Kentucky.) Farley said the calculation factors in Japan’s lower labor and currency costs, as well as higher expenses his company faces from Trump’s array of tariffs, including those on steel and aluminium via higher prices charged by Ford’s suppliers.

How reliant is the US on auto imports?

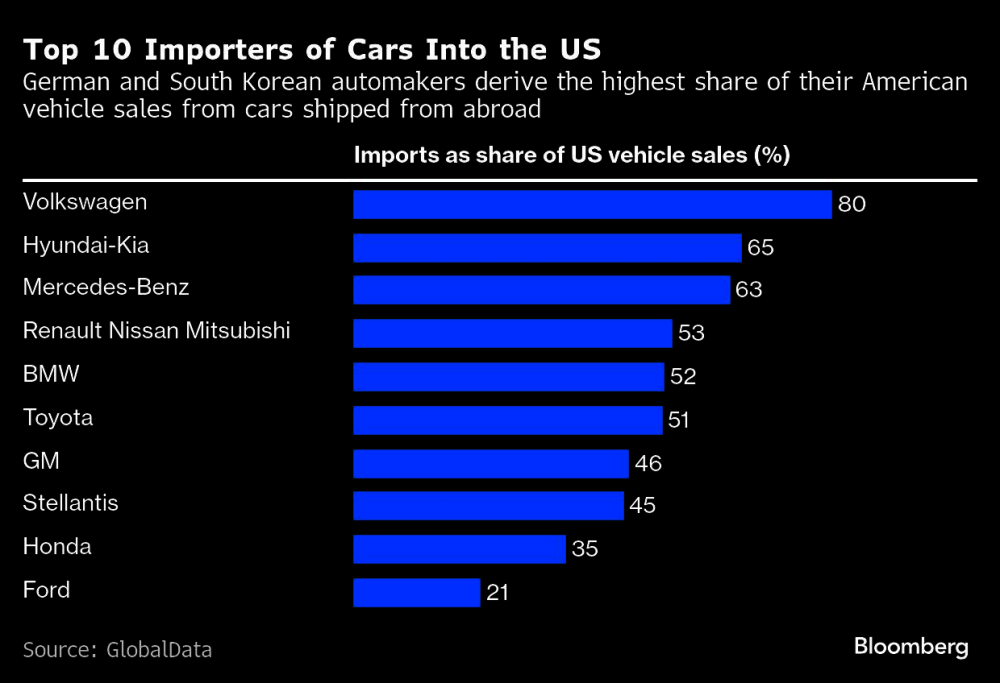

Very. Around 50% of the roughly 16mn new passenger vehicles sold in the US in 2024 were assembled outside of America, according to automotive researcher GlobalData. Most of those imports came from five countries: Mexico, Japan, South Korea, Canada and Germany.

Even historic US car brands make a lot of their vehicles in other countries. America’s largest automaker, GM is also its top auto importer by volume. It brought 1.23mn cars into the US last year, according to GlobalData, including more than 400,000 vehicles from its factories in South Korea, where it makes the relatively budget-friendly Trax and Trailblazer, both Chevrolet SUVs.

In percentage terms, 46% of GM’s US sales come from imported cars. That leaves the company more exposed to tariffs than its fellow Detroit automakers — Ford and Stellantis — but better positioned than most of its European and Asian rivals.

Toyota is the second-biggest importer of cars into the US, leaning on these shipments for just over half of its US sales. The carmaker imported 1.2mn vehicles into America last year, including more than 500,000 from Japan. Hyundai, meanwhile, sent 1.1mn vehicles to the US last year — including Kia and Genesis branded models — which accounted for almost two-thirds of its American sales. The vast majority of those cars came from its home country, South Korea.

Is there such a thing as a 100% made-in-America vehicle?

No. A substantial portion of the content in vehicles built in the US comes from factories abroad. A White House fact sheet said a conservative estimate of the average share of foreign content is 50%, but that the true figure is likely to be closer to 60%.

North America’s car manufacturing sector is particularly interconnected. The USMCA and its predecessor Nafta have allowed automakers to effectively operate as if there were no borders for the past 30 years, taking advantage of Canada’s natural resources, Mexico’s low-cost labour, and the huge consumer market in the US. Raw materials and parts often move between the three countries several times before making it into an assembled car. So assigning the plethora of new tariffs for vehicles sold in the US will be a complex operation.

How is Tesla affected by tariffs?

Tesla has been touted as one of the automakers that will feel the least pain from Trump’s auto tariffs, because it produces all the electric vehicles it sells in the US at factories in California and Texas.

But only around 60-75% of the components Tesla uses for those EVs are manufactured in America or Canada, depending on the model, according to a 2024 filing by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The majority of the remaining parts come from Mexico.

When the company was given the opportunity by the Trump administration to comment on the government’s trade practices, the EV maker said there was only so much that it can procure in the US. “Even with aggressive localisation of the supply chain, certain parts and components are difficult or impossible to source within the US,” unidentified Tesla representatives wrote in a letter to Jamieson Greer, the US trade representative, dated March 11.

How have automakers reacted to Trump’s tariffs?

Many withdrew their financial forecasts for the year due to tariff uncertainty. Some, such as Jeep maker Stellantis, have paused production in Canada and Mexico, while others have announced plans to increase manufacturing in the US. GM, for example, plans to spend $4bn to boost production at its US factories over the next two years, trimming its exposure to imports from Mexico.

The automaker hopes relocating some parts production, internal cost cuts and other measures will offset at least 30% of its $5bn exposure to the duties this year.

Ford, meanwhile, expects the tariffs to squeeze its 2025 earnings by about $3bn, and hopes to offset $1bn of that through cost cuts. The automaker offered discounts across almost its entire lineup for most of the year to keep customers coming to showrooms. It has also hiked the sticker price on three models built in Mexico by as much as $2,000, according to a company memo to dealers seen by Bloomberg News.

The profit squeeze shows how automakers have thus far preferred to absorb higher tariff costs rather than raise prices. But dealers will eventually run out of cars built before the tariffs took effect. Industry watchers broadly expect prices to go up later this year.

Beyond the US automakers, embattled Nissan Motor Co of Japan has decided to stop selling a pair of Mexican-built SUVs in the US and reversed a decision to cut production of the Rogue compact crossover SUV at its plant in Tennessee.

Mercedes-Benz Group AG plans to shift production of a “core segment vehicle” to its factory in Alabama by 2027. But it’s also weighing whether to pull its least expensive cars, such as the GLA small SUV, from the market, because the tariffs could turn already-thin profit margins into losses if the additional costs aren’t passed on to customers, Bloomberg reported.

How will Trump’s tariffs impact car prices in the US?

American drivers were already being squeezed before the tariffs landed. The average sticker price of a new passenger vehicle in the US was around $47,500 as of March, a 22% increase from five years earlier, according to data from valuation specialist Kelley Blue Book. As car prices have risen and high interest rates have made for expensive financing, delinquencies on auto loans were hovering near their highest level in more than 30 years in March.

And now import taxes have been added to the mix, threatening to drive vehicle prices up even further. Automakers and parts manufacturers can absorb some of the added costs, but in most instances, at least some of the extra expenses will eventually be passed on to consumers.

The impact could be particularly pronounced at the cheaper end of the market, as many of the least expensive models are built outside the US to maximise already-low profit margins. Ford, for example, assembles its Maverick compact pickup truck, which starts at $27,000, in Mexico, while GM ships its Buick Envista, which has a base price of $25,095, from South Korea.

There’s much speculation over just how much car prices could go up due to the auto tariffs, but the consensus is that the increase will be in the region of thousands of dollars.

Taking into account the revisions Trump made to the levies, consulting firm Anderson Economic Group estimates prices could rise by more than $12,000 for luxury SUVs, battery-powered EVs and cars assembled in Europe and Asia. Even vehicles made in the US with substantial domestic content could see $2,000 to $3,000 added to their price tag.

How long will it take for tariffs to impact car prices in the US?

Any price increases may not materialise immediately, as dealers typically stock two to three months’ supply of new cars. That said, the rush to buy vehicles ahead of the new import taxes kicking in has reduced pre-tariff inventories more quickly than usual, which could lead to a summer sticker price shock.

Higher prices won’t just be a new car problem. As prices climb for vehicles fresh off the assembly line, many buyers will likely look for second-hand alternatives, pushing up the prices of those too. And with auto parts due to join the tariffs mix, repairs will get even more expensive and insurance premiums could rise as well to cover the higher breakdown costs.

How easy is it to shift auto production to the US?

There won’t be an immediate surge in US car manufacturing. While carmakers can look to increase output at their existing American plants, new factories — for both vehicle assembly and parts production — would require billions of dollars and take years to complete. It’s also an expensive process to wind down plants elsewhere.

To commit to such investments, companies need to be assured of a stable business environment, and there’s little visibility over whether Trump’s on-again, off-again tariff strategy could result in the auto levies being amended again within days, weeks or months — either up or down.

For some manufacturers, the economics of setting up shop in America may just not stack up. For most component producers, it would be more expensive to produce in the US than paying the 25% tariff, according to Bank of America analysts.

And even if Trump succeeds in coaxing companies to build more vehicles in the US, his intended jobs boom may not follow, as companies could lean on automation rather than large numbers of human workers to keep production costs down.