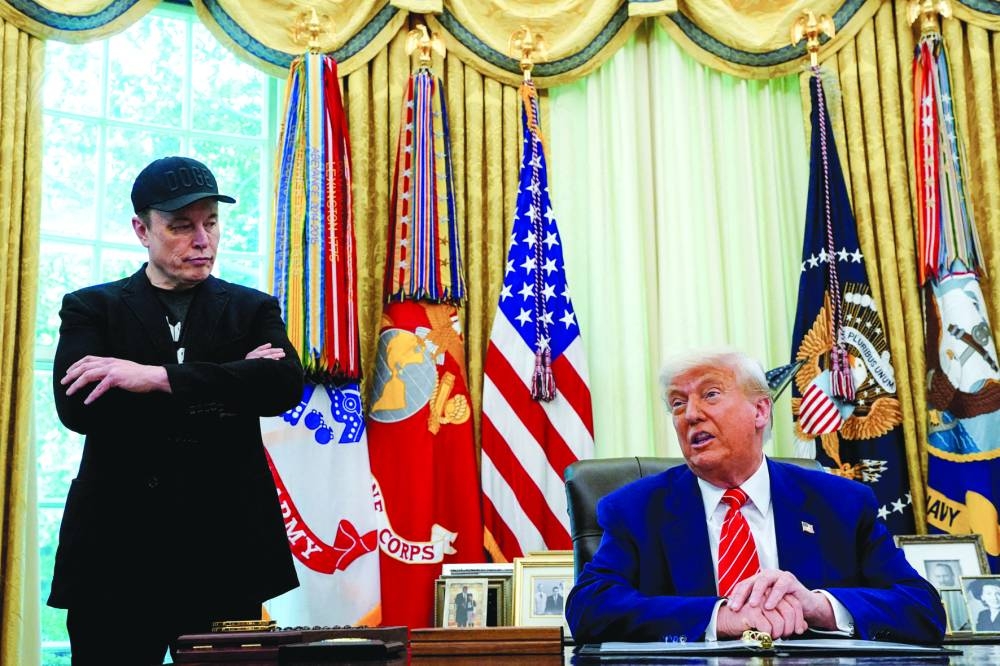

Musk’s comments triggered an escalating exchange of threats and recriminations between him and Trump (each relying on his own social media platform). But as of this week, Musk has had enough. Having deleted several incendiary posts and issued an apology, he appears to have learned the hard way what happens when a private empire picks a fight with a sovereign.

The asymmetry is razor sharp: A country issuing its own currency cannot go bankrupt like a corporation, yet it can wield fiscal, regulatory, and legal powers capable of bankrupting private enterprises. Investors took notice and showed how quickly political risk can rattle markets. During Musk and Trump’s contretemps, Tesla shares plunged 14% in a single day, erasing $150bn in market value with no other news.

But this is not just about a tech mogul walking back a few impulsive tweets. Musk’s first big mistake was to treat the Treasury as if it were a corporate finance department. His claim that adding roughly $2-2.5tn to the deficit would bankrupt America applied balance-sheet logic to a currency-issuing sovereign – a category mistake. In business, too much debt can indeed force bankruptcy. But the US government cannot run out of dollars. It can always create the money it owes, which is not true for companies, households, or even the world’s richest person.

The salient risk, then, is not government insolvency, but inflation. If deficit spending outpaces the economy’s productive capacity, it can drive up prices, erode household purchasing power, and lead to higher interest rates that raise borrowing costs. Inflation typically produces investor unease, causes sovereign-bond yields to rise, and places downward pressure on the currency. These are all serious economic costs, but they do not rise to the level of insolvency. The US cannot be forced into default on its dollar-denominated debt.

Eurozone countries are in a different position, because they don’t control the currency they use. Since the euro is issued by the European Central Bank, countries like Greece, Italy, or Spain cannot create the currency with which to service their debts. If their revenues collapse or their borrowing costs surge, they cannot print euros to close the gap. Their ability to repay depends wholly on decisions made by a central authority that they don’t control. Eurozone governments can suffer the same kind of solvency crisis that businesses can, whereas countries like the US and Japan cannot.

At the same time, governments can inflict devastating harm on private actors by withdrawing contracts, rescinding subsidies, tightening regulations, or launching investigations – all levers that no private rival can match. Musk’s apology reflected this asymmetry. His enterprises – Tesla, SpaceX/Starlink, Neuralink – have been highly dependent on government contracts, subsidies, and regulatory approvals. By withholding these forms of support, Trump can inflict tens of billions of dollars of losses on Musk, who as a private magnate lacks any reciprocal mechanism to bankrupt the Treasury.

True, some government agencies have become dependent on Musk’s companies. SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft is now Nasa’s only operational transport for US crew; without it, Nasa would have to go back to relying on Russian Soyuz capsules to reach the International Space Station. Still, the US government could have withdrawn its backing for Musk’s companies, tightened its oversight of them, or launched burdensome official inquiries.

Musk underestimated just how dependent his own businesses are on state support. Notably, his apology came after Trump threatened “very serious consequences” in response to Musk’s threat to shift his financial support away from Republicans. Such a public retreat demonstrates that money may buy access, but it provides no shield against the unrivalled tools of state power.

Misapplying corporate logic to public finance does not just mislead the public. It also can invite political and regulatory blowback from an entity that is far more resilient than any private enterprise. In today’s political climate, even industry titans like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, the owner of the Washington Post, have adjusted their posture to avoid the Trump administration’s ire. When business interests depend on federal goodwill, any act of dissent can be perilous.

Musk’s money aided Trump’s election campaign last year, but now Trump’s political power threatens Musk’s empire. If nothing else, by vividly demonstrating that the Treasury is not Tesla, their dispute has contributed to informed public debate about fiscal policy. When people mistake government debt for corporate debt, they demand the wrong policies, ultimately weakening public institutions and destabilising the private sector that depends on them. – Project Syndicate

- Carla Norrlöf, Professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto, is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.