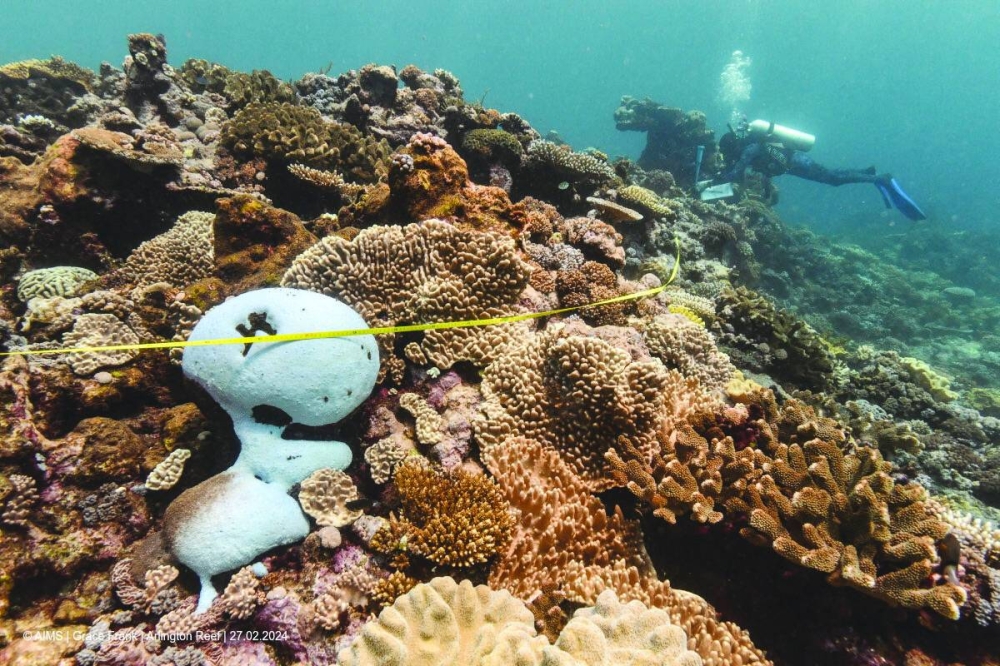

Along coastlines from Australia to Kenya to Mexico, many of the world’s colourful coral reefs have turned a ghostly white in what scientists said amounted to the fourth global bleaching event in the last three decades.

At least 54 countries and territories have experienced mass bleaching among their reefs since February 2023 as climate change warms the ocean’s surface waters, according to the US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Coral Reef Watch, the world’s top coral reef monitoring body.

Announcement of the latest global bleaching event was made jointly by the NOAA and the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI), a global intergovernmental conservation partnership.

For an event to be deemed global, significant bleaching must occur in all three ocean basins – the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian – within a 365-day period.

Recurring bleaching events are upending earlier scientific models that forecast that between 70%-90% of the world’s coral reefs could be lost when global warming reached 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures.

To date, the world has warmed by some 1.2C (2.2F).

In a 2022 report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, experts determined that just 1.2C of warming would be enough to severely impact coral reefs, “with most available evidence suggesting that coral-dominated ecosystems will be non-existent at this temperature”.

The consequences of coral bleaching are far-reaching, affecting not only the health of oceans but also the livelihoods of people, food security, and local economies.

Severe or prolonged heat stress leads to corals dying off, but there is hope for recovery if temperatures drop and other stressors such as overfishing and pollution are reduced.

“As the world’s oceans continue to warm, coral bleaching is becoming more frequent and severe,” said Derek Manzello of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “When these events are sufficiently severe or prolonged, they can cause coral mortality, which hurts the people who depend on the coral reefs for their livelihoods.”

The NOAA’s heat-stress monitoring is based on satellite measurements from 1985 to the present day.

The current bleaching event is the fourth on record, with previous events in 1998, 2010 and 2016.

Coral – which are marine invertebrates made up of individual animals called polyps – have a symbiotic relationship with the algae that live inside their tissue and provide their primary source of food.

When the water is too warm, coral expel their algae and turn white, an effect called “bleaching” that leaves them exposed to disease and at risk of dying off.

Since early 2023, mass bleaching of coral reefs has been confirmed throughout the tropics, including in Florida in the United States, the Caribbean, Brazil, and the eastern Tropical Pacific.

Florida’s 2023 heatwave started earlier, lasted longer and was more severe than any previous event in that region ever recorded, said the NOAA.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the largest coral reef system in the world and the only one visible from space, has also been severely impacted, as have wide swathes of the South Pacific, the Red Sea and the Gulf.

“We know the biggest threat to coral reefs worldwide is climate change. The Great Barrier Reef is no exception,” Australia’s Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek said recently.

Often dubbed the world’s largest living structure, the Great Barrier Reef is a 2,300km (1,400 miles) expanse of tropical corals that house a stunning array of biodiversity.

Repeated mass bleaching events have threatened to rob the tourist drawcard of its wonder, turning banks of once-vibrant corals into a sickly shade of white.

Roughly 850mn people worldwide rely on coral reefs for food, jobs and to protect coastlines from storms and erosion, according to the nonprofit WWF.

The ecosystems provide a haven for ocean life, with over a quarter of marine species calling them home.

The NOAA estimates the world has already lost 30-50% of its coral reefs already, and they could disappear entirely by the end of the century without significant intervention.

“If we need a specific, visual, contemporary case of what’s at stake with every fraction of a degree warming, this is it,” said the WWF’s Pepe Clarke. “The scale and severity of the mass coral bleaching is clear evidence of the harm climate change is having right now.”

“What is happening is new for us, and to science,” said marine ecologist Lorenzo Alvarez-Filip at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “We cannot yet predict how severely stressed corals will do even if they survive immediate heat stress.”

“A realistic interpretation is that we have crossed the tipping point for coral reefs,” said ecologist David Obura, who heads Coastal Oceans Research and Development Indian Ocean East Africa from Mombasa, Kenya. “They’re going into a decline that we cannot stop, unless we really stop carbon dioxide emissions that are driving climate change.”

Despite the grim outlook, the NOAA said it had made “significant strides” in developing interventions against coral bleaching.

These included “moving coral nurseries to deeper, cooler waters and deploying sunshades to protect corals in other areas”.

Scientists are seen conducting in-water monitoring in Arlington Reef, Australia, amidst bleached coral reefs, in this handout picture obtained by Reuters.