Manager Joerg Engelmann says he has pulled out all the stops to attract skilled foreign workers to his chemical engineering company in Chemnitz, east Germany. But once they arrived, the racial slurs and exclusion they experienced in the town have driven some of them away.

His firm is one of five German medium-sized companies that told Reuters their foreign staff recently moved on or switched locations due to xenophobia, even as Europe’s biggest economy suffers a shortage of skilled labour.

Many large companies in Germany and The Netherlands have expressed concern about the difficulty of hiring due to anti-immigrant sentiment. Some employers go a step further, saying they are actually losing staff because of it.

CAC Engineering GmbH, the family-owned company Engelmann runs, has lost around five of its 40 foreign employees over the past 12 months because of discrimination, he told Reuters. The company declined to make its former staff available to Reuters.

“We do what we can. But we can’t become bodyguards,” said Engelmann, 57. “There are parts of the population who don’t realise that these are foreign skilled workers who want to make a real contribution in Germany.”

CAC did not give details, but xenophobic hate crime cases recorded across Germany by the interior ministry more than tripled between 2013 and 2022 to more than 10,000. Overall, Engelmann said, high energy costs pose a bigger challenge.

Official German estimates suggest the country as a whole will be short of seven million skilled workers by 2035, compared with a labour force of around 46 million.

The climate is more hostile in eastern Germany, where after the fall of communism plant closures and layoffs saw an exodus of young people and a lower birth rate.

Chemnitz, in the state of Saxony near the Czech border, is trying to attract skilled workers — Engelmann’s firm says it helps arrange temporary housing, language and even driving lessons to encourage foreign employees to settle.

But Chemnitz has become a focus of anti-immigrant feelings since 2018 when anti-migrant protests in the city turned to riots.

Largely destroyed during World War Two and rebuilt under Communism as Karl-Marx-Stadt, it was one of Germany’s richest cities at the turn of the 20th century.

Since reunification in 1990, its population has shrunk by around 20% to just over 250,000. Foreigners have jumped to nearly 14% of inhabitants from just over 2% in 2000, according to data from Chemnitz-based FOG Institute for Market and Social Research.

On Monday evenings at around 6pm, around 250 people march through the town in a regular “Monday demonstration” promoted by one of the far-right parties that make up a quarter of the city council’s members. Marchers at a recent event sang nationalist songs, beat drums and waved the flags of Saxony, Germany and Russia.

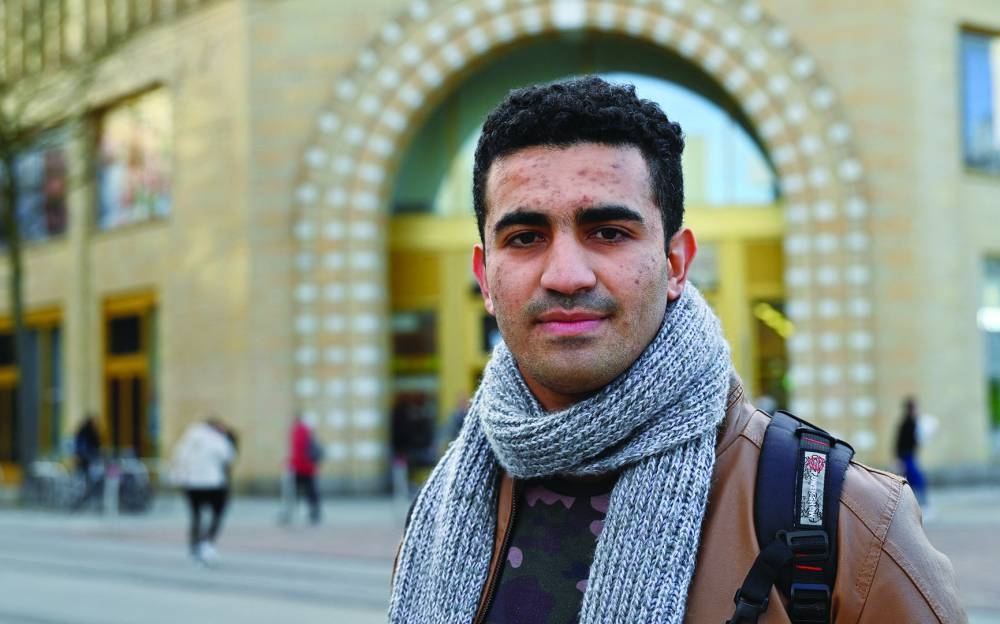

Resident Farid Mokbil, 31, an Egyptian who came to Germany to teach German to foreigners, said he is happy in the town overall: He experiences racism often but doesn’t take it personally.

“In the first week here I went shopping at the supermarket and an elderly woman just looked at me — I’m not sure if it was my appearance — but she just started shouting,” he said. “Such weird situations happen ... A few days ago in the tram, a boy said loudly, ‘here there are only Afghans who want to steal.’”

Christine Willauer, 84, a lifelong Chemnitz resident, said she felt asylum-seekers in Germany got financial benefits that the elderly did not.

“When I am in the city, some days I feel there are not many people speaking my own mother tongue anymore,” she said. “I also miss the old manners.”

City spokesman Matthias Nowak said the majority of people in Chemnitz are against extremism, adding that Chemnitz would “fall apart” without immigrants — for instance, 40% of staff at the hospital are foreigners.

Channelling the anti-immigrant mood are political parties including Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD), which is on track to win three regional state elections in September this year including in Saxony.

The AfD has said it wants to reverse mass migration that occurred in 2015, create asylum centres outside the European Union, introduce strict controls on German borders, sanction migrants who do not integrate fully and create incentives for economic migrants to return home.

Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, which has said it is monitoring the AfD on suspicion of extremism, says AfD party officials propagate racist theories such as the “Great Replacement,” which holds that political elites are deliberately engineering the replacement of Europe’s white population with non-white immigrants.

The party’s Chemnitz chapter this month shared an article on its Facebook page about an alleged rape by migrants entitled “population replacement makes girls and women fair game.”

In one post, Ulrich Oehme, deputy leader of AfD Chemnitz, comments that “life for our women and girls has become much harder in public spaces and worries about group rape and knife attacks are on the rise.”

Oehme told Reuters his post was not xenophobic, but was addressing “issues felt massively by the local population.” The AfD said it agreed with his observations, adding: “Immigration-related crime is very difficult to combat because it is often embedded in family or clan structures and because of cultural and language barriers.”

Facebook owner Meta did not respond to a request for comment.

The AfD says its policies would not damage the economy.

“Here the government and state-owned companies are clearly and obviously distracting from the home-made problems and using the AfD as a scapegoat,” it said in a statement to Reuters, citing the high energy prices worsened by Germany’s nuclear exit and renewables drive.

But Germany’s corporate executives took to the media to warn about the risks of anti-immigrant sentiment, following a January report by investigative portal Correctiv of a fundraising meeting in Potsdam where a “masterplan” for deportations of people of foreign origin — dubbed “remigration” — was discussed.

Attended by four senior AfD officials, the meeting was organised by a group called the Duesseldorfer Forum, which said on the invitation it is an “exclusive network of ... personalities who are ready to make significant contributions to ... stop the destruction of our country.”

On a microsite created after the event, organiser Gernot Moerig said remigration was only one topic discussed. He could not be reached for comment.

Martin Sellner, an Austrian leader of the Identitarian Movement, which says it wants to preserve European identity and opposes immigration from outside the continent, told Reuters he had spoken at the meeting.

“Unassimilated citizens like Islamists, gangsters and welfare cheats should be pushed to adapt through a policy of standards and assimilation,” he said, saying that could include incentives for voluntary return.

“In the long-term, a German remigration policy sets the course for ... Germany to become more German every day and not the opposite.”

The hardening climate extends beyond Chemnitz, and does not only target people from outside Europe.

“Two of our foreign employees have left Germany because they said that they no longer feel comfortable and safe here,” said Detlef Neuhaus, CEO of solar firm SolarWatt, based in the east German city of Dresden. He said one had moved back to England.

“These are direct consequences of the changing mood in the country.”

The company declined to make its former staff available to Reuters.

Chemnitz-based Community4you, which supplies fleet and leasing software to corporate heavyweights such as Lufthansa, BMW and Commerzbank, said it has had employees move away because they no longer feel welcome.

Its Chief Operating Officer Lavinio Cerquetti, an Italian, moved northwest to Leipzig in 2021, saying the atmosphere was more cosmopolitan there.

“In Chemnitz, I sometimes had the feeling that the fact that I had to be careful was also related to the fact that I was a foreigner,” he said.

Autonomous driving software maker FDTech, also based in Chemnitz, has also lost workers over xenophobia, its managing director Karsten Schulze said.

“Yes, we do have a problem with xenophobia here. But it’s not limited to Saxony, to Chemnitz, we have it all across Germany. And by the way, all across Europe, too,” he said.

Germany’s economy shrank by 0.3% in 2023, the weakest performance globally among large countries.

A survey carried out over 2022 and 2023 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has highlighted that while Germany remains very attractive to foreign workers, discrimination is a problem.

Tracking the careers of 30,000 highly qualified people who wanted to come to Germany as migrant workers since August 2022, the survey found that people who had already moved to Germany experienced more discrimination compared to the expectations of those still abroad.

Essen-based Deniz Ates, 30, who runs recruitment agency Who Moves that focuses on foreign IT workers, said he first noticed at an event in India late last year that people were worried about the political mood in Germany, with some saying the country was no longer an option for them.

“The most important factor in deciding where to apply for a job is: Do I feel safe? Do I feel welcome?” Ates said.

New Delhi-based lawyer Romy Kumar said he has put on hold efforts to relocate to Europe, where he spends several months a year, citing a rise in xenophobia.

“This limits your risk-taking abilities to jump on the next plane and go there and set up something,” he said. “So that is why I’m taking it slow and trying to assess where is it going.”

Chemnitz city spokesman Nowak said it had increased funds for anti-racism and pro-democracy projects since 2018 and wants to use plans for its coming role as a European Capital of Culture in 2025 to activate the “silent middle,” addressing the issue of racism head-on.

Far-right parties have said they will protest this. One, Pro Chemnitz, has suggested the city should instead be the “capital of remigration.”

“We have had enough of the kind of culture that has flooded Germany since 2015 — all you need to do is check the city centre,” the party said in post on Telegram. The party did not respond to a request for comment from Reuters.

Opinion

Racial tensions costing Germany Inc. skilled foreign labour

Five medium-sized companies say their foreign staff recently moved on or switched locations due to xenophobia

Protesters carry national flags of Germany and the ultra far-right party Freie Sachsen (Free Saxony) during a demonstration in Chemnitz. (Reuters)

Farid Mokbil, an Egyptian who lives in the East German city of Chemnitz, poses for a photo following a Reuters interview in Chemnitz. (Reuters)