It is the season of political parties’ annual conferences in the United Kingdom. While much of the attention will be on the governing Tories, many also will be closely watching the Labour Party, now that it is significantly ahead in the polls.

In the weeks leading up to the Conservative Party conference, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak seems to have shifted his personal strategy. Rather than presenting himself as a competent, safe, unambitious pair of hands, he is making a show of bold promises to tackle the country’s biggest challenges. But is he serious, or is this mere political theatre timed for the election?

Sunak, after all, presides over a party that is riddled with factions – many of them ideologically committed, and all of them scarred by the infighting of the past 13 years. Moreover, the party’s current MPs were elected in 2019 by a strange mix of traditional Tory constituencies and newer Brexit-oriented voters who previously voted Labour. Both cohorts rather like government spending when it is directed toward them, provided that their own tax bills don’t go up.

Hence, in the run-up to this year’s conference, some Tories have once again trotted out the dream of lower taxes, decrying the tax burden borne by many households, and blaming this supposed problem on the country’s weak economic performance in recent years. Michael Gove, a member of the cabinet, has even come out and said that while he personally favours income-tax cuts before the next election, Sunak and the chancellor of the exchequer have ruled them out.

In fact, though the UK tax burden has risen somewhat in recent years, it remains notably lower than in other developed countries. According to the UK’s own fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s tax-to-GDP ratio in 2021 (33.5%) was 2.2% below the developed-country average, 3.3% below the G7 average, and a whopping 6.4% below that of 14 other peer European countries, many of which have much higher standards of living. Of the countries that are wealthier than the UK in terms of per capita GDP (Britain ranks 22nd globally), more have a higher tax burden than have a lower one.

But not only do the data fail to support the argument that taxes are the main drag on UK growth; polling in recent years has shown that the British electorate generally favours higher taxes for the sake of higher spending (though many presumably would prefer that someone else bear the additional burden). This marks a shift from the 1990s and the 2000s, suggesting that higher taxes and spending do not pose the same political risk they once did to an incumbent government.

Still, any Tory leader, no matter how skilled, would struggle to navigate the current political and policy landscape, given the party’s own decisions in government since 2010 and the endless internal squabbles they have inspired. Moreover, after 13 years in the political wilderness, Labour is focused squarely on demonstrating that it would be more competent with public finances and deliver stronger growth.

Earlier this year, Labour leader Keir Starmer and his shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, issued a mission statement pledging to achieve the fastest growth in the G7. (One hopes they mean per capita GDP, not absolute GDP, since that is what matters to households and correlates more strongly with productivity performance.) They also would enhance the powers of the OBR, which regularly estimates the costs of government programs and the tax policies needed to support them. This point matters because the OBR was (in) famously sidelined by former prime minister Liz Truss, whose extremely short stint in office almost crashed the entire economy.

Moreover, a few weeks ago, Labour went further by vowing that, if elected, no major tax or spending decision would be implemented without the OBR having publicly issued an independent analysis of the policy’s implications (presumably for growth and the public balance sheet).

In response, George Osborne, who created the OBR while serving as chancellor for the Tory-led coalition government back in 2010, has suggested that Sunak’s administration should adopt this proposal immediately. As a means of reinforcing the UK’s fiscal “credibility,” it has much to recommend it. But unless it results in tax and spending policies that are both more realistic and more ambitious, its effects will be limited.

As the data make clear, the UK suffers from persistently weak public- and private-sector investment, relative to its peers. Unless that changes, achieving rapid per capita GDP growth will be a pipe dream.

A smart government would stop playing the political game of focusing excessively on arbitrary short-term tax-to-GDP levels, and instead pursue an agenda that raises that ratio for the express purpose of boosting investment spending and productivity. Both are needed to sustain long-term growth and to reduce long-term debt. If the OBR’s independent analysis determines that such spending will require increased taxes, so be it. That will be the ultimate test of the government’s seriousness. – Project Syndicate

l Jim O’Neill, a former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management and a former UK treasury minister, is a member of the Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development.

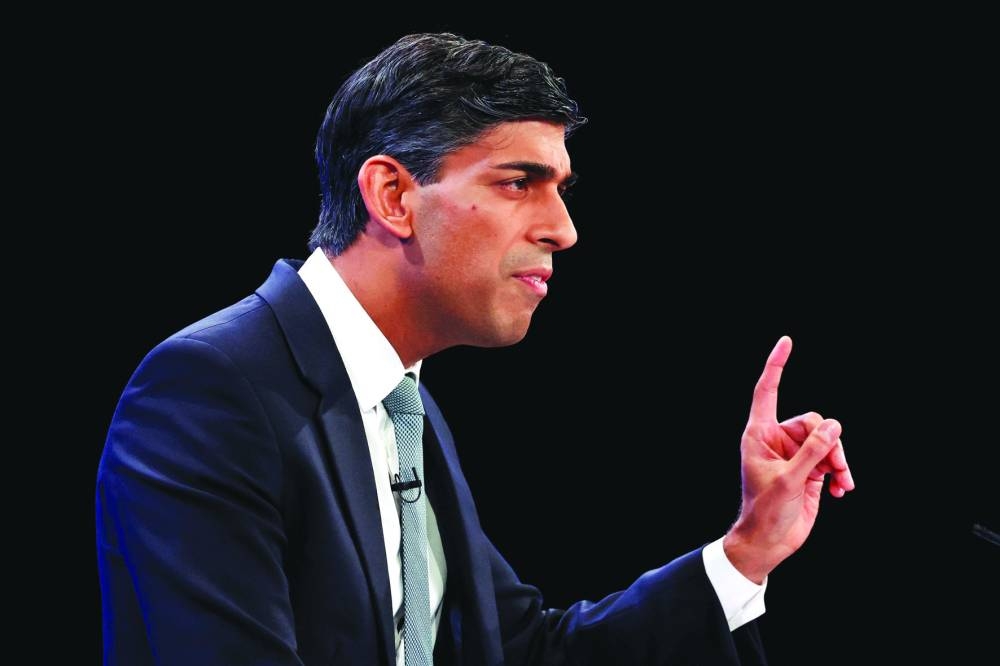

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak speaks on stage at Conservative Party’s annual conference in Manchester yesterday.