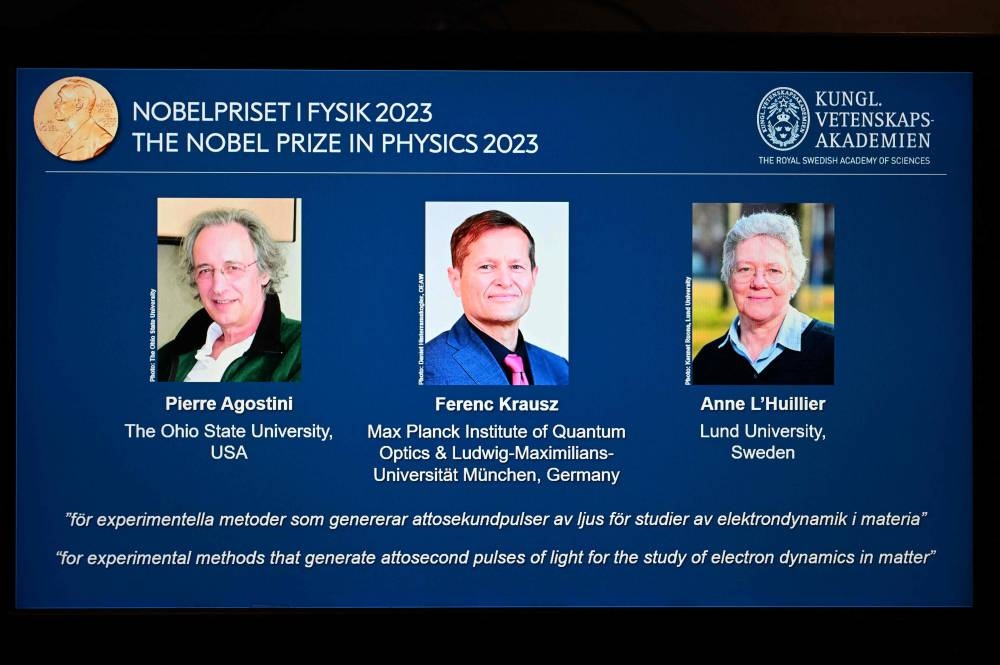

Johannes LEDEL France's Pierre Agostini, Hungarian-Austrian Ferenc Krausz and Franco-Swede Anne L'Huillier won the Nobel prize in physics on Tuesday for research using ultra quick light flashes that enable the study of electrons inside atoms and molecules.

Their technique employs pulses measured in attoseconds, a unit so short that there are as many in one second as there have been seconds since the universe's birth over 13 billion years ago, the jury said.

The laureates' research has made it possible to examine moves or changes so rapid that they were previously impossible to follow, with potential applications in both electronics and medical diagnostics.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences likened the process to how the flapping wings of a humming bird turn into a blur for the human eye, but can be slowed and examined using high-speed photography.

"We can now open the door to the world of electrons. Attosecond physics gives us the opportunity to understand mechanisms that are governed by electrons," Eva Olsson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said in a statement.

In 1987, L'Huillier "discovered that many different overtones of light arose when she transmitted infrared laser light through a noble gas," the Nobel Committee noted, adding that her exploration of the phenomenon laid "the ground for subsequent breakthroughs".

In the early 2000s, Agostini and Krausz worked on how to isolate light pulses that lasted only a few hundred attoseconds.

Agostini is a professor at Ohio State University in the United States, while Krausz is a director at the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

"It was just atomic physics interacting with lasers," Agostini said of his early work, in an interview released by his university. "We were not really aware it would go that far, but a lot of people were interested both in the method and the result."

L'Huillier, only the fifth woman to be awarded the Physics Prize since 1901, is a professor at Lund University in Sweden.

She told reporters she was in the middle of teaching a class when she received the call from the Academy, making it "difficult" to finish the class, to whom she did not reveal the news.

"I am very touched ... There are not so many women that get this prize so it's very, very special," she said.

Before L'Huillier, Marie Curie (1903), Maria Goeppert Mayer (1963), Donna Strickland (2018) and Andrea Ghez (2020) are the only women to have won the award.

Speaking later at a press conference, she encouraged young women interested in science to "go for it" and said it was possible to combine a research career with an "ordinary life, with a family and children."

French President Emmanuel Macron congratulated the trio.

"What a source of pride for our nation!" Macron said in a post to X, formerly known as Twitter.

L'Huillier and Krausz had been seen as contenders for the honour, having been awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize last year together with Canadian physicist Paul Corkum.

However, Krausz said he had not been expecting a call.

"I was not sure whether I was dreaming or whether it was reality," he told the Nobel Foundation in an interview.

The physics award is the second Nobel of the season after the Medicine Prize on Monday, awarded to messenger RNA researchers Katalin Kariko and Drew Weissman for their groundbreaking technology that paved the way for mRNA Covid-19 vaccines.

Krausz said he had actually been listening to an interview with Kariko when he received the call, adding he was especially impressed with her determination as she toiled away at her research despite struggling to achieve recognition and secure funding for it.

"That's what I would like to convey to future generations," Krausz said.

The Physics Prize will be followed by the Chemistry Prize on Wednesday, with the highly watched Literature and Peace Prizes to be announced on Thursday and Friday.

The Economics Prize -- created in 1968 and the only Nobel not included in the 1895 will of Swedish inventor and philanthropist Alfred Nobel, which founded the awards -- closes out the 2023 Nobel season on Monday.

(L-R) A tablet shows this year's laureates US-based physicist Pierre Agostini, Hungarian-Austrian physicist and French physicist Anne L’Huillier during the announcement of the winners of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics at Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm on October 3, 2023. AFP

French-Swedish physicist Anne L'Huillier, talks to journalists at Lund University, in Lund, Sweden after the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm announced that she won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics. Ola TORKELSSON/TT News Agency/AFP

Picture released on October 3, 2023 shows French Physicist Pierre Agostini who won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics.AFP / OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY

Hungarian-Austrian physicist Ferenc Krausz reacts after the announcement of the winners of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics at the Max-Planck Institute in Garching. AFP