A decade after Indigenous leader Alicia Cahuiya made a speech in Ecuador’s parliament to protest against oil exploration in the Amazon basin, she finally has something to celebrate.

In a first-of-its-kind national referendum last month, Ecuadorians voted to halt oil operations in Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (43-ITT) block in the Yasuni Amazon reserve, where production by state oil company Petroecuador started in 2016.

Environmental activists say the ban will protect one of the planet’s most biodiverse rainforests, and safeguard some of the world’s last Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation.

“They finally stopped damaging our Amazon, our home, our dwelling, and I am very happy and proud,” Cahuiya said in an interview.

Yasuni, which was declared a Biosphere reserve by the United Nations in 1989, has several hundred species of trees and animals, and is home to three uncontacted communities — the Tagaeri, Taromenane and Dugakaeri — Indigenous leaders say.

The vote — which means Petroecuador has a year to stop production in the 43-ITT block — is set to reduce Ecuador’s 480,000-barrel-per-day (bpd) crude oil output by 12%.

The referendum came at a time when the future of fossil fuel exploration and extraction in Latin American nations was in the spotlight after the Colombian government last year said it wanted to phase them out as part of a clean energy transition.

In August — a fortnight before the plebiscite in Ecuador took place — the leaders of the eight Amazon nations met in Belem, Brazil, at a regional summit where they agreed on unified environmental policies but not on a goal to end deforestation.

During the event, Colombia’s first leftist president, Gustavo Petro, pushed for a ban on all new oil development in the Amazon, but his request was rebuffed by the other countries.

Central and South America account for 6.8% of the world’s oil production, says the Energy Institute, a global industry body.

Despite Colombia’s proposal being rejected in Belem, Kevin Koenig of the NGO Amazon Watch said he believed there was “new momentum” across Latin America to move away from fossil fuels.

“Years ago, the only real voice of resistance and opposition to some of these (planned exploration) projects was from local affected communities. But now that’s changed,” said Koenig.

“We’re seeing national Indigenous organisations. We’re seeing civil society. We’re seeing, to some extent, members of government all expressing and flirting with the idea that they need to keep fossil fuels in the ground,” he added.

Koenig cited Peru and Colombia as examples, highlighting how they had long held aspirations of opening massive auctions of new exploration areas yet pointing out that those plans had been rescheduled or that bids for blocks had failed to materialise.

This is partly related to the commitments of several international investors when it comes to environmental and social governance standards, according to Koenig, the climate, energy and extractive industry director at Amazon Watch.

“There is a global interest in taking care and saving the Amazon and protecting the lives of those who live there.”

One way of achieving this could involve Latin American nations asking for donor funding to facilitate a green energy transition, according to several activists and academics.

Ecuador tried this in 2007, when then-President Rafael Correa launched an appeal to leave the nation’s oil reserves in the ground if the international community donated $3.6bn. The plan was shelved in 2013 after failing to get near the goal.

Yet Carlos Larrea Maldonado, coordinator of the environment and sustainability program at Simon Bolivar Andean University, said there are now “many more possibilities than in 2007” — citing more awareness of the issue, greater availability of funding, and the backing of some governments in the region.

Maldonado said Latin American nations could potentially benefit from Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) — donor deals struck so far with Senegal, Indonesia, Vietnam and South Africa to help them move away from fossil fuels — mainly coal — by mobilising public and private finance.

“This has not been applied to oil yet, but it could be done in the case of Peru, Colombia and also Ecuador,” he said.

However, industry and climate analysts say Latin America is not ready to wean itself off fossil fuels, highlighting recent oil discoveries in countries like Argentina, Brazil and Guyana.

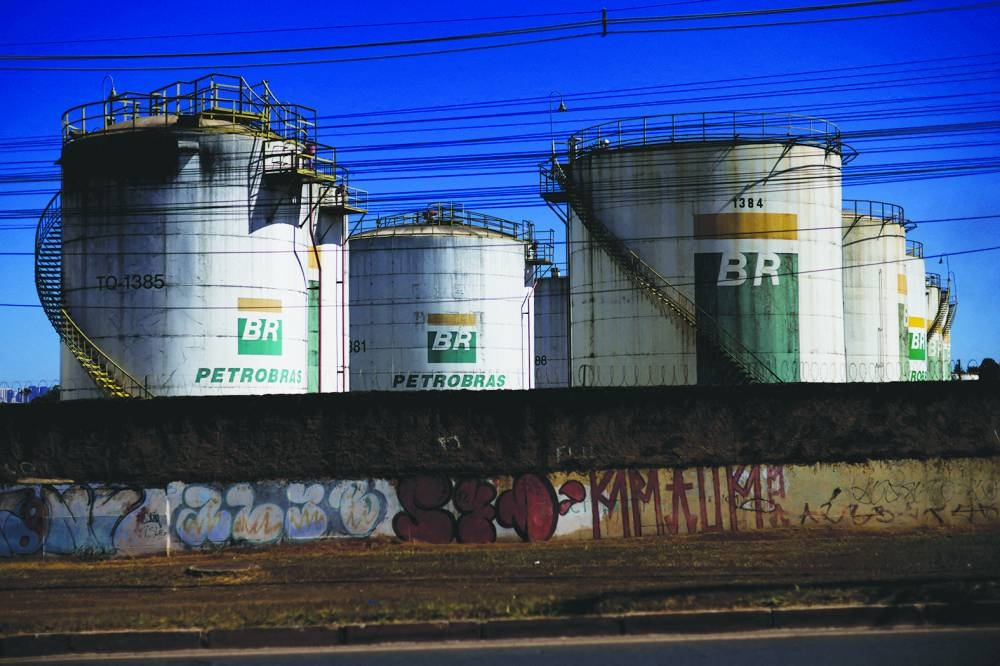

While most new oil projects are located far from the Amazon, one high-profile exception is Brazilian state-run oil company Petrobras’ plan to drill at the mouth of the Amazon river.

Brazil’s environmental protection agency, Ibama, has denied Petrobras permission to drill an exploratory well, saying the request lacks an environmental assessment of the project. The company has appealed the decision.

Suely Araujo, a former head of Ibama and policy specialist at the Brazilian Climate Observatory, said that while the result of the Ecuador referendum would inspire social movements against fossil fuels in other Latin American countries, the prospect of any such vote in Brazil would be highly unlikely.

“In the Brazilian case ... national plebiscites are very rare, even in governments that seek to open opportunities for popular participation, such as the current one,” he said, referring to the left-wing rule of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

More broadly, there is little chance of a wave of similar referendums on fossil fuel extraction happening any time soon in the region — or other parts of the world — according to Aditya Ravi, an analyst at Oslo-based consultancy Rystad Energy.

Oil represents a key pillar of Ecuador’s economy. The industry accounts for roughly 11.3% of the country’s GDP and about a third of its annual national income, according to the National Association of Hydrocarbon Producers, a sector body.

Before the referendum, Energy Minister Fernando Santos stated his opposition to the closure of the 43-ITT block and said it would cost Ecuador $1.2bn in oil income per year.

After the plebiscite, the government said it would honour the result, and that Petroecuador must withdraw from the block within a year.

Environmental organizations like Yasunidos — the collective which first pushed for the referendum 10 years ago — said it would fight to ensure the decision is respected and enforced.

“In Ecuador, everything won in the ballot box must be defended later on,” said Yasunidos member Alejandra Santillana, who is a researcher at the Institute of Ecuadorian Studies. — Thomson Reuters Foundation

Opinion

Ecuador’s Amazon oil ban a threat to LatAm fossil fuels?

• Ecuadorians vote to halt oil drilling in the Amazon

• Colombia pushed for ban on new extraction in rainforest

• Analysts say Latin America not ready to ditch fossil fuels

A general view of the tanks of Brazil’s state-run Petrobras oil company following the announcement of updated fuel prices at the Brazilian oil company Petrobras in Brasilia. (Reuters)