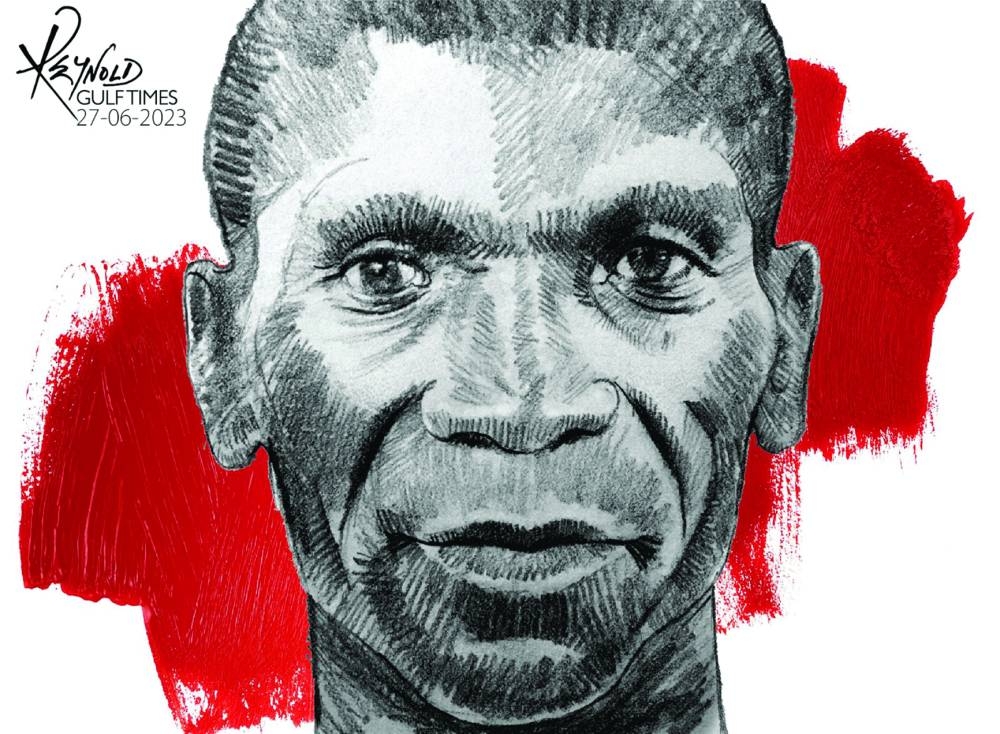

Two months on from his disappointing performance at the Boston marathon, Eliud Kipchoge says he is determined to keep on writing history - and secure a third Olympic marathon crown next year.

The Kenyan widely regarded as the greatest marathon runner of all time has set himself many challenges in his dazzling career, and remains insatiable despite his two Olympic titles, his world record of 2:01:09 in Berlin in 2022 and an incredible 15 wins in 18 marathons he has entered.

He broke the mythical two-hour barrier over the 26.2 mile (42.195 kilometre) distance in Vienna in 2019, with a time of 1:59:40, but the feat was not recognised as an official world record as it was not in open competition.

Victory has eluded the 38-year-old in the Boston and New York marathons, which if he won would make him the first man to have all six major titles under his belt.

“The priority now is to focus on the Olympics and win a third time. The other (challenges) will come later,” Kipchoge said at the renowned Kaptagat training camp in Kenya’s Rift Valley.

His two Olympic marathon gold medals in 2016 and 2021 put him at level pegging with Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila (1960, 1964) and Waldemar Cierpinski of East Germany (1976, 1980).

A third gold at the Paris Olympics in 2024 would make Kipchoge the undisputed marathon giant at the Games, and bring him a victory steeped in symbolism.

The French capital was the city where he won his first international crown in 2003 at the age of 18, clinching the 5,000 metres world championship title ahead of sporting legends Hicham El Guerrouj of Morocco and Ethiopia’s Kenenisa Bekele.

However, Kipchoge does not rule out giving up on his other goals.

“If time comes in to hang the racing shoes, I will say bye to other big things in sport.”

Sitting on a shaded bench in the Kaptagat camp where he has lived and trained for several months a year for 20 years, Kipchoge looks back on his poor showing in Boston on April 17, where he dropped from the lead group in the 30th kilometre and ended up finishing sixth. This rare failure dampened his spirits.

“I’m trying to forget what has happened in Boston. It’s caught in my mind... but I believe that what has passed has passed.”

With his lifelong coach Patrick Sang, he has analysed the reasons for his disappointing performance, saying “it’s mostly the hamstring”.

He brushes aside concerns about his difficulties on hilly courses such as Boston and New York and which will also confront him in Paris.

“It is not really a concern, but I respect everybody’s thoughts,” he says. “I think it was a bad day and every day is a different day. I’m looking forward for next year.

“Everybody can write anything, you have no control. But I know myself.” Kipchoge is now preparing for his final marathon of the year.

“I’m doing well. My training is going on in a good way,” he says.

But he has not yet disclosed which event it will be - Berlin on September 24, Chicago on October 8 or New York on November 5.

“At the end of July, I will know where to go.” He is following his usual training programme, eating up more than 200 kilometres a week on the red dirt tracks of Kaptagat forest, 2,400 metres above sea level.

Among his 20-odd training partners at the camp at the time of the AFP interview were Kenya’s new 1,500m and 5,000m world record holder Faith Kipyegon and two-time New York marathon winner Geoffrey Kamworor.

As the respected dean of Kenyan athletics, Kipchoge is happy to see the emergence of 23-year-old compatriot Kelvin Kiptum, who won the London Marathon in April in 2:01:25, the second fastest time in history and just 16 seconds away from his own world record.

“I want to be an inspiration and I trust my breaking the world record twice is an inspiration to many young people. I trust they will want more and even beat my records.”

But in a country where athletics has become tainted by large-scale drug use, Kipchoge laments that “many people are going into shortcuts to advance”.

“I think doping is there... It’s all more about getting rich.”

Kipchoge says the authorities should prioritise testing for performance-enhancing substances, saying it was much more important than education “because everybody who is doing doping knows what is going on”.

“Just pump everything in testing, put testing as a first priority and all will be well,” he says.

“The moment we prioritise testing and we register those who are handling the athletes across the country, we have the right data to know who is who in the whole country.

“But if we really ignore the people who are working with athletes and athletes themselves, then we are in danger.”

Kipchoge