The 2008 global financial crisis exposed the horrendous mistakes that banking regulators had made in the preceding years. But rather than correcting them and developing a robust understanding of why these errors were committed and how they could be avoided in the future, politicians and the public at the time demanded that supervisory authorities simply double down on regulation. So, that is what they did, and we are now seeing the results.

The main mistake in contemporary banking regulation is the requirement of only a razor-thin capital cushion. This is an artifact of a previous era. It is based on the capital that Japanese zombie banks had in the mid-1990s, reflecting the desire among those writing the Basel rules (the international banking regulation framework) not to embarrass their colleagues at the Bank of Japan.

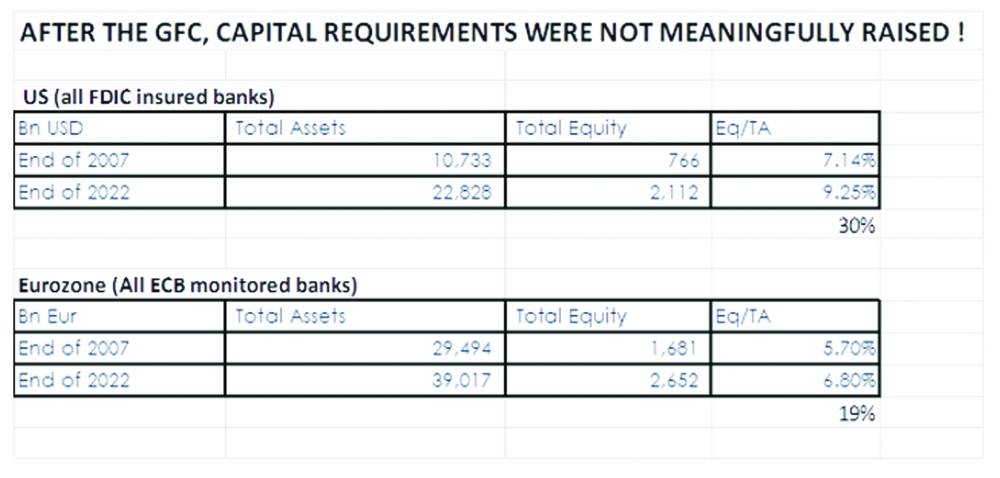

After the global financial crisis, it was again too embarrassing to recognise the extent of this mistake, so policymakers and regulators settled on a more gradual approach. As a result, since 2007, capital as a share of total assets has risen by less than 30% in Europe and the United States. True, Tier 1 ratios (the ratio of equity and reserves to risk-weighted assets) improved by more, but that was largely achieved by tweaking the rules for calculating the numerator and the denominator. Capital would have tripled if banks had been required to carry the same ratio that hedge funds carry voluntarily for the same level of risk.

Look at SVB. It had $200bn in assets, $86bn of which was in residential mortgage-backed securities that are not due for at least ten years, and which are carried on a held-to-maturity basis. At fair value, though, this paper was worth only $71bn, implying a $15bn loss. That amount was more than enough to wipe out the bank’s $12bn in capital, and it was written clearly in the bank’s 2022 financial statements.

In practice, the prevailing “prudential” regulations allowed SVB to leverage its capital more than tenfold on that book of risky securities. Given the volatility of the assets, that is insane. Even an aggressive hedge fund would not have leveraged such a book by more than threefold. But SVB was allowed to operate and publish a Tier 1 ratio of 12%, well within the “prudential” limits.

That brings us to the second major uncorrected mistake of banking regulation: solvency is assumed to rest on a held-to-maturity basis. Even “conservative” banking experts such as John Vickers, a former chief economist of the Bank of England, seem to accept this. But would Vickers leave a deposit with a bank that is insolvent on a mark-to-market basis? No, he would not, and nor did SVB’s depositors. When they finally realised what should have been clear for many months, they tried to withdraw their money as fast as they could.

This problem would seem to apply only to the US. In Europe, we have regulated liabilities (through the net-stable-funding ratio) and assets (through the liquidity-coverage ratio), so this kind of mismatch should not happen. But as comforting as this arrangement may be, it also means that the authorities have regulated the interbank lending market out of business – and probably the banks as well. Who will leave a deposit at a bank that can achieve only yields below those of the high-quality liquid assets in which the banks and depositors themselves can invest? Banks will remain confined to the payments business, at least until central bank digital currencies arrive, and transfer that business to the central bankrupters too.

Do we want capitalism or not? If we do, we need to get rid of the failed regulations (and regulators), and end the status quo in which central bankers preside over monetary policies with long, variable, and lagging effects, and hence have an impact on future economic conditions that they cannot predict.

We also need to stop thinking that bank deposits are the only financial asset whose price is fixed at par and guaranteed by the nanny state. If banks financed themselves through traded certificates of deposit, crises like the current one would not happen. SVB’s CDs might be priced at 85%, owing to the uncertainty surrounding a liquidation or a recapitalisation, but there never would have been a run on the bank. The runs happen only because the first 85% of people in line would get par, while only the last 15% would get zero. — Project Syndicate

- Antonio Foglia, a board member of Banca del Ceresio, is a member of the Global Partners’ Council of the Institute for New Economic Thinking.