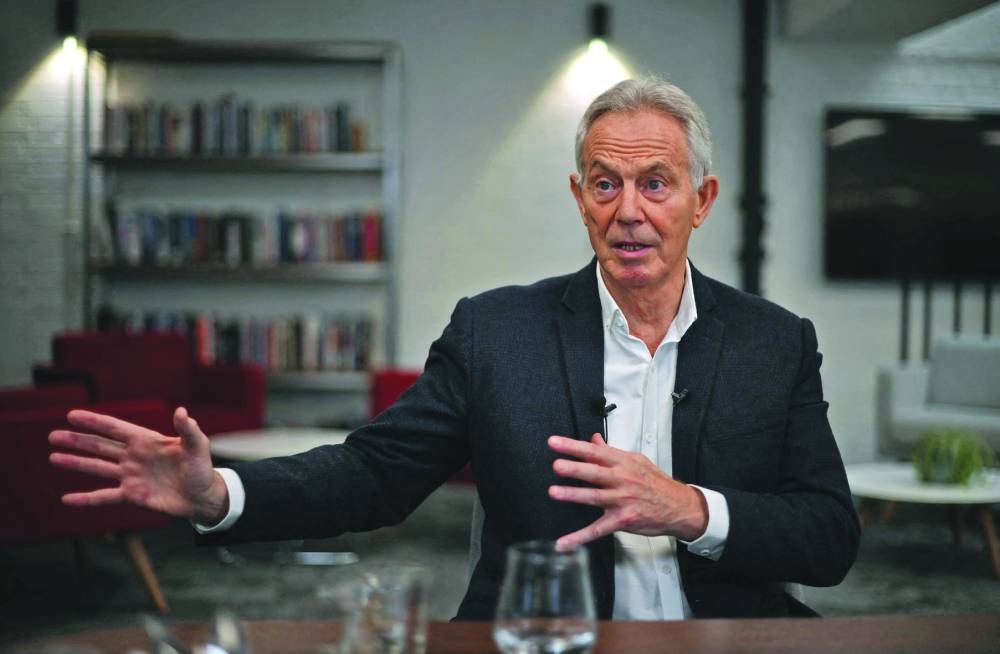

Former UK prime minister Tony Blair is by turns pensive and defiant as he reflects on the upcoming anniversaries of two events that arguably defined the best and worst of his decade in power.

Monday marks 20 years since Blair joined US president George W Bush in launching an invasion of Saddam Hussain’s Iraq, without a UN mandate and in defiance of some of the biggest demonstrations ever seen in Britain.

For its many critics, the war was exposed as a reckless misadventure when no weapons of mass destruction were found, and hampered the West’s ability to stand up to the rise of autocrats in Russia and China.

However, Blair rejects the notion that Russian President Vladimir Putin profited by defying a weakened West with his own aggression against Ukraine, starting in 2014 and extending to last year’s full invasion.

“If he didn’t use that excuse (Iraq), he’d use another excuse,” Britain’s most successful Labour leader, who is now 69, said in an interview with AFP and fellow European news agencies Ansa, DPA and EFE.

Saddam, Blair noted, had initiated two regional wars, defied multiple UN resolutions and launched a chemical attack on his own people.

Ukraine in contrast has a democratic government and posed no threat to its neighbours when Putin invaded.

“At least you could say we were removing a despot and trying to introduce democracy,” Blair said, speaking at the offices of his Tony Blair Institute for Global Change in central London.

“Now you can argue about all the consequences and so on,” he continued. “His (Putin’s) intervention in the Middle East (in Syria) was to prop up a despot and refuse a democracy. So we should treat all that propaganda with the lack of respect it deserves.”

Fallout from the Iraq war arguably hampered Blair’s own efforts as an international envoy to negotiate peace between Israel and the Palestinians, after he left office in 2007.

Through his institute, Blair maintains offices in the region and says that he is “still very passionate” about promoting peace in the Middle East, even if it appears “pretty distant right now”.

However, while there can be no settlement in Ukraine until Russia recognises that “aggression is wrong”, he says the Palestinians could draw lessons from the undisputed high point of his tenure: peace in Northern Ireland.

Under the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, pro-Irish militants agreed to lay down their arms and pro-UK unionists agreed to share power, after three decades of sectarian strife had left some 3,500 people dead.

Blair, then Irish premier Bertie Ahern and an envoy of US president Bill Clinton spent three days and nights negotiating the final stretch before the agreement was signed on April 10, 1998.

The territory is mired in renewed political gridlock today.

However, a recent deal between Britain and the European Union to regulate post-Brexit trade in Northern Ireland has cleared the way for US President Joe Biden to visit for the agreement’s 25th anniversary.

Reflecting on the shift in strategy by the pro-Irish militants, from the bullet to the ballot box, Blair said “it’s something I often say to the Palestinians: you should learn from what they did”.

“They shifted strategy and look at the result,” he added, denying that he was biased towards Israel but merely recognising the reality of how to negotiate peace.

“There are lots of things contested and uncontested,” he added, dwelling on his tumultuous time in 10 Downing Street from 1997-2007.

“I suppose the one uncontested thing is probably the Good Friday Agreement,” he said. “The thing had more or less collapsed when I came to Belfast and we had to rewrite it and agree it ... it’s probably been the only really successful peace process of the last period of time, in the last 25 years.”

International

Putin can’t use Iraq as justification for actions on Ukraine, says Blair

Former UK prime minister Tony Blair is by turns pensive and defiant as he reflects on the upcoming anniversaries of two events that arguably defined the best and worst of his decade in power.

Former British prime minister Tony Blair speaks during an interview in central London.