The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank threatens to further besmirch the reputation of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, on top of the blemish he’s suffered for being slow to recognise the risk of rampant inflation.

Friends and foes of the Fed alike have faulted the central bank for not heading off the troubles at the nation’s 16th-largest lender before they blew up into a crisis that shook the financial system and prompted extraordinary steps by policymakers over the weekend to contain it.

“There was a supervisory failure,” said former Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo, who oversaw the central bank’s regulatory portfolio in the wake of the 2007-09 financial crisis and is now a Harvard Law School professor.

A number of lawmakers and central bank watchers are criticising the Powell-led Fed board for wholeheartedly signing on to a Republican-driven agenda in 2018 to loosen regulation on banks smaller than behemoths such as JPMorgan Chase & Co and Bank of America Corp. They argue that Powell and his team at the time — some of whom have since left the Fed — are at least partly responsible for the problems at SVB.

Experts are divided, though, over how much, if any, blame to directly assign to Powell. Some – including frequent Fed critic Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution – say Powell couldn’t have been expected to know the nitty gritty details of one of the hundreds of banks the central bank supervises.

If Powell succeeds in navigating the current financial ructions and brings inflation down without a painful recession, he’ll be lionised for managing a particularly tricky transition.

But it’s a transition made all the more difficult by the delay in which the Fed reacted to inflation and the speed at which it subsequently moved to jack up interest rates.

In Washington, Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a long-time Powell foil, has been out front in slamming the Fed chief over the SVB affair.

“Powell’s actions to allow big banks like Silicon Valley Bank to boost their profits by loading up on risk directly contributed to these bank failures,” she said in a statement Tuesday.

Other lawmakers have been more reticent in pinning blame on the Fed chair, with several Republicans pointing the finger at supervisors at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco – which directly oversaw the operations of SVB.

Powell on Monday launched an internal review of the Fed’s supervision and regulation of SVB after its failure last week. The appraisal, which will be led by Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr, will be publicly released by May 1. Senate Banking Committee Chair Sherrod Brown told Bloomberg Television on Tuesday that he believes Powell will investigate the circumstances behind SVB’s collapse properly. That’s in contrast to the stance taken by his Banking Committee colleague Warren, who called on Powell to recuse himself from the Fed’s review.

The Fed is considering changes to its oversight of mid-sized banks, including rules that could bring capital and liquidity thresholds closer to strictures that the largest Wall Street firms face, according to a person familiar with the matter.

As recently as early 2021, Powell was being hailed for the critical role that he and the Fed played in helping to pilot the economy through the thick of the pandemic the year before.

But his reputation was tarnished by his repeated insistence in 2021 that the surge in inflation then taking hold was “transitory.” He then pivoted in the following year to overseeing the most aggressive monetary tightening campaign since the 1980s to try to rein prices back in.

Those rapid-fire rate increases contributed to the problems at SVB, as its holdings of otherwise ultra-safe Treasury and agency bonds lost value. It also experienced an exodus of deposits, with technology companies yanking money out of the bank as their businesses slowed under the impact of tighter credit.

There’s widespread agreement among banking experts that state supervisors in California, those at the San Francisco Fed and to a lesser extent at the Fed board in Washington, either missed or failed to act quickly enough to correct some glaring problems at SVB. The issues included a massive bond position not hedged against the vagaries of interest rates and over-reliance on deposits above the $250,000 level insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

“Each one of these alone is a classic red flag,” said Klein, who worked on the banking reforms that grew out of the 2007-09 financial crisis as an official at the Treasury and is also a former chief economist at the Senate Banking Committee. “Combined, it’s a red laser beam.”

But what’s less clear is whether that was solely the result of a mistake made by supervisors on the ground, or whether it also partly reflected a more relaxed attitude toward oversight of smaller banks conveyed by the Powell-led Fed board in Washington — particularly, former Vice Chair for Supervision Randal Quarles.

In a January 2020 speech in Washington, Quarles — an appointee of former President Donald Trump — outlined a variety of changes to the supervisory process.

He said supervisors should “focus on violations of law and material safety and soundness issues” and shouldn’t “mistakenly give the impression that supervisory guidance is binding.” Quarles left the Fed in October 2021.

What’s also unclear is how much of the SVB debacle can be tied to 2018 legislation that loosened regulatory scrutiny for many regional banks and to the actions that the Powell-led Fed took in carrying the law out.

That legislation was spearheaded by Republicans and the Trump administration, but was passed with significant Democratic support. It was also backed by since-deposed SVB Chief Executive Officer Greg Becker.

Dennis Kelleher, CEO at Better Markets, an organisation advocating stricter financial regulation, said Powell can’t duck responsibility for the SVB collapse.

“He supported Quarles in implementing rules that went far beyond the law in deregulating the banks,” Kelleher said.

Tarullo sees only a modest connection between the regulatory changes made by Congress in 2018 – and the Fed’s implementation of them – and the specific failure of SVB.

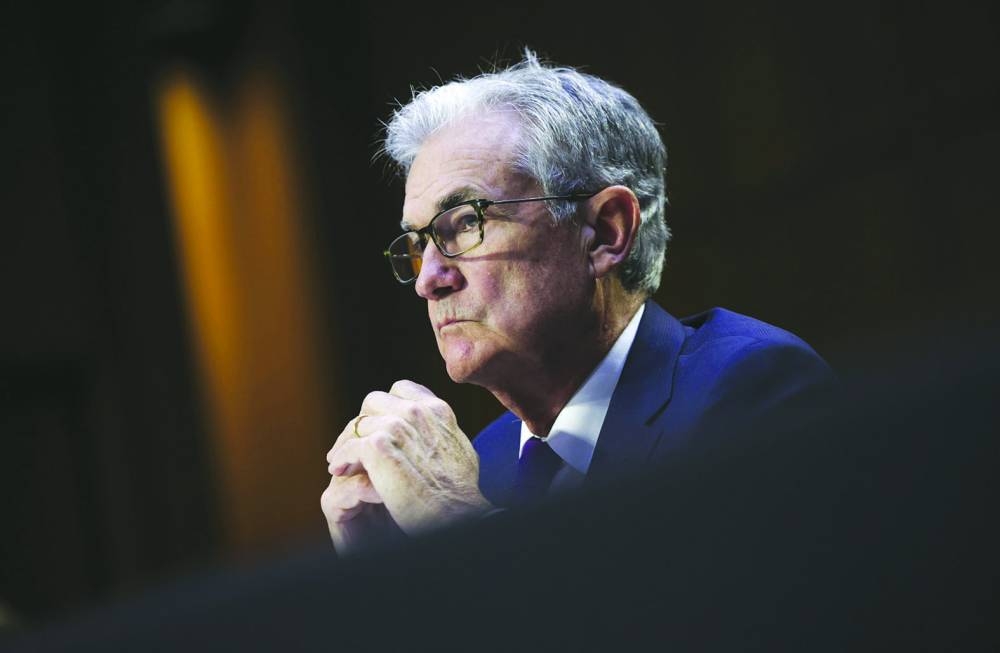

Jerome Powell, chairman of the US Federal Reserve.