Consumer inflation in the United States slipped in December to the lowest level in more than a year, government data showed yesterday, signalling the worst of red-hot price increases may be over.

As American households struggled with decades-high inflation in the past year, the Federal Reserve hiked its benchmark lending rate at a pace unheard of since the 1980s, in hopes of cooling the world’s biggest economy.

Inflation has eased for a sixth consecutive month alongside the Fed’s aggressive campaign, fuelling hope for reprieve from steeply rising interest rates.

The consumer price index (CPI) last month rose 6.5% from a year ago, the smallest increase since October 2021, said the Labor Department. This figure is also down from November’s 7.1% spike.

“The index for gasoline was by far the largest contributor to the monthly all items decrease,” said the department.

This more than offset increases in the shelter component, with elevated rents still boosting consumer costs.

Between November and December, CPI dipped 0.1%.

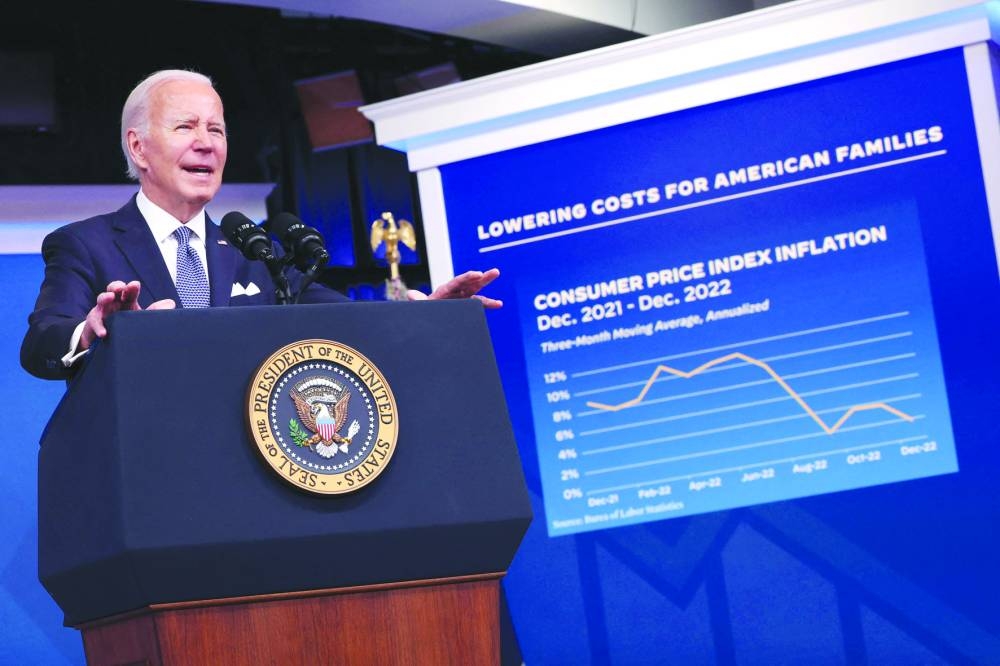

While there is some way to go in curbing inflation, “we’re clearly moving in the right direction,” President Joe Biden told reporters yesterday.

“And there’s more breathing room in store for American workers and families,” he said.

Moody’s Analytics economist Matt Colyar told AFP that “the trend is an encouraging one,” noting that figures have come down from a recent peak.

Rubeela Farooqi of High Frequency Economics added that this could “support another step down in the pace of rate hikes” at the Fed’s February policy meeting.

But she warned in a recent note that “rates of change remain well above levels Fed officials are comfortable with.”

US consumer inflation climbed rapidly to a blistering 9.1% last June, a 40-year high, as the war in Ukraine sent global food and energy costs rocketing.

While the pace has eased, it remains far from the Fed’s two-percent target.

Prices at the pump — a key area where consumers feel the pinch — dropped last month on lower global demand and falling oil prices, in welcome news to policymakers. But such costs are volatile, meaning “the Fed cannot rely on this to be a consistent source of disinflation,” said Ryan Sweet of Oxford Economics.

While the food index picked up month-on-month in December, the pace slowed as well, data showed.

But components that increased include shelter, household furnishings and motor vehicle insurance.

Stripping out the volatile food and energy segments, the “core” CPI index rose 0.3% from a month prior, in line with expectations.

This was a slight pick-up from November’s 0.2% reading, signalling the battle to rein in costs is not yet over.

It is “troubling” that services inflation has risen, with higher rents likely to persist for the first half of the year, Sweet of Oxford Economics told AFP.

“The tug-of-war between those two, whether goods disinflation is going to be enough to offset services inflation, is going to be very important,” he said.

For now, the Fed is keeping a close eye on the labour market and the pace of wage growth, as rapidly rising earnings could feed into the costs of services too.

Fed chair Jerome Powell cautioned on Tuesday that “restoring price stability when inflation is high can require measures that are not popular in the short term” as interest rates rise.

Business

US inflation hits slowest pace in over a year amid hopes of less hawkish Fed

Consumer inflation in the United States slipped in December to the lowest level in more than a year, government data showed yesterday, signalling the worst of red-hot price increases may be over.

US President Joe Biden delivers remarks on the economy and inflation in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building yesterday in Washington, DC. While there is some way to go in curbing inflation, “we’re clearly moving in the right direction,” he told reporters.