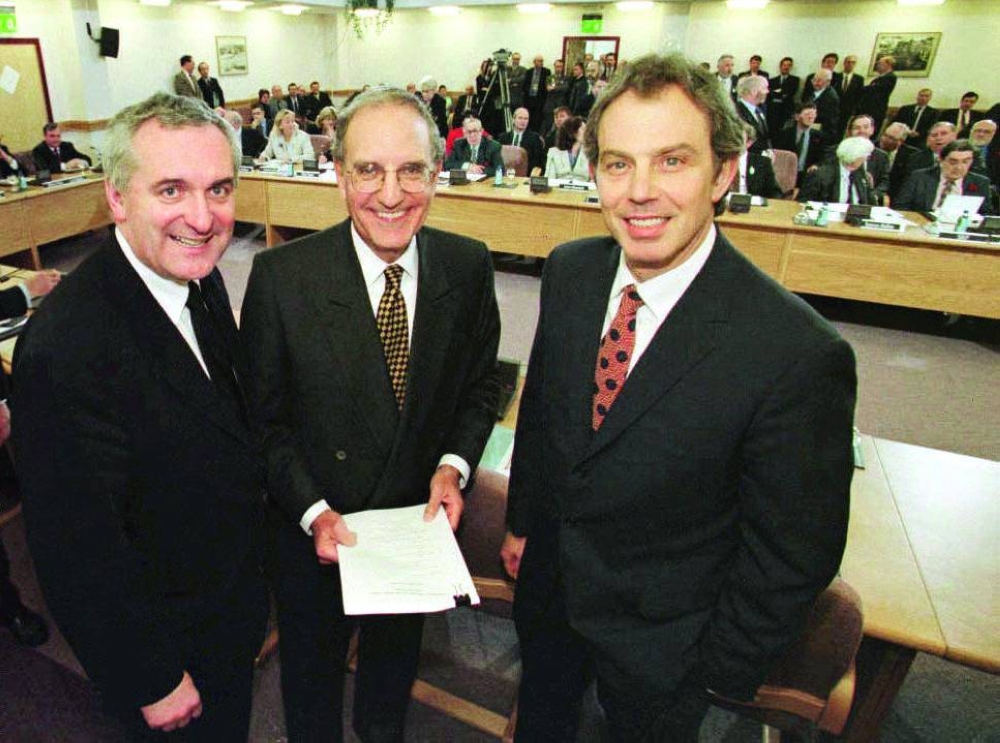

Irish state documents covering the build-up to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 and its immediate aftermath showed yesterday the scale of the challenge to decommission weapons stockpiles held by Northern Ireland’s paramilitaries.

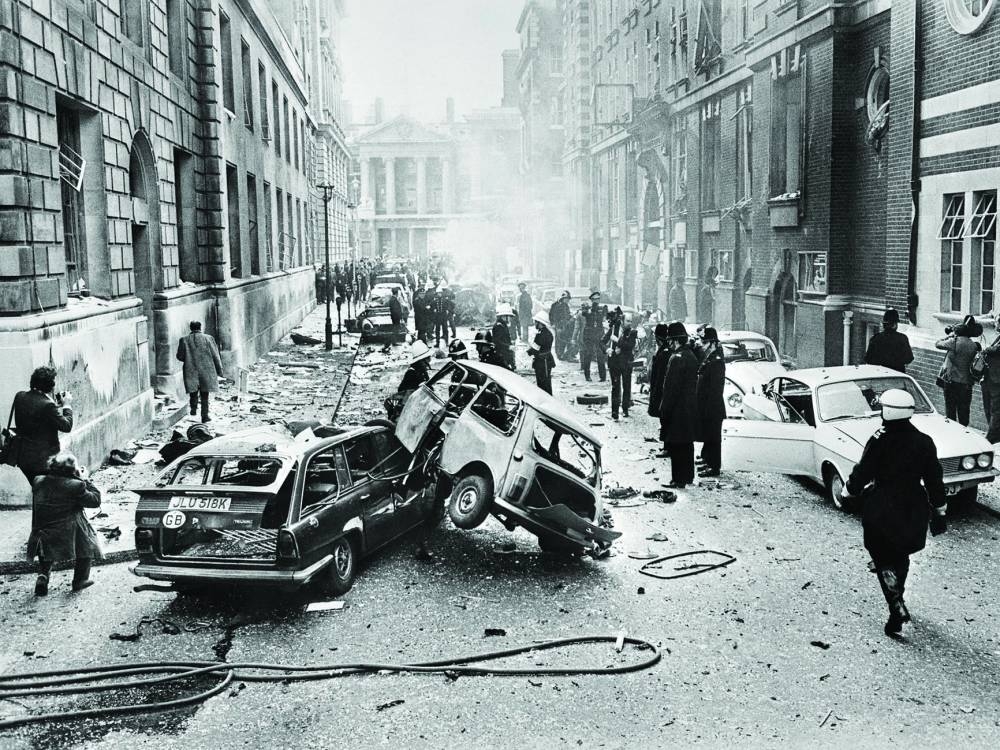

The 1998 peace accords, the result of years of painstaking diplomacy, brought an end to “The Troubles”, three decades of sectarian conflict over British rule in Northern Ireland which left 3,500 dead.

However, in the years before the deal was struck and in those that followed, the thorny issue of decommissioning arms from the conflict – particularly those held by the nationalist Irish Republican Army (IRA) – regularly threatening the peace process.

An October 1997 document from Northern Ireland’s decommissioning body to the Irish government, contained within newly released state archives, gives estimates of weapons caches calculated following meetings with security officials.

The Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD) said that it believed there were as many as 1,100 rifles and 1,200 pistols held by armed groups, up to 60 machine guns and 30 sniper rifles with 1mn rounds of ammunition.

It said that according to reliable reports the groups possessed sophisticated weapons such as RPGs, anti-armour grenades and flamethrowers as well as improvised mortars and sub-machine guns.

The body also detailed that paramilitaries in the conflict – which was often characterised by bomb attacks against both military and civilian targets – had “substantial holdings” of improvised explosive devices and likely up to 3,000kg of explosives.

The Good Friday Agreement stipulated Northern Ireland’s political parties would seek to achieve decommissioning by May 2000, a deadline that would be missed and extended repeatedly.

Northern Ireland’s largest pro-UK party, the Ulster Unionists, threatened repeatedly to walk away from the peace deal and the new power-sharing government over the issue of IRA decommissioning.

Ronit Hobson, an expert at Queen’s University Belfast, told AFP that at the time of the agreement “expectations were very low for decommissioning”.

“There was an understanding that decommissioning is not a point that you can push too hard on,” she added.

A transcript of a call between then-Irish premier Bertie Ahern and British prime minister Tony Blair just three months after the Good Friday deal shows the two leaders straining to hold together the fragile peace.

Blair told his Irish counterpart that Gerry Adams, leader of the IRA’s political wing Sinn Fein, “has got to deliver something on the decommissioning front and something on the war is over front”.

“We’re still honouring everything so I think they have to ... do something in return quite simply,” Ahern replies.

A memo recording a meeting between Adams and an Irish official in October 1998 showed Dublin putting pressure on the Sinn Fein leader, who said the IRA’s position was that it will “never decommission”.

As the impasse over disarming dragged on, a 1999 note to Ahern suggested considering the option that “actual decommissioning in the sense which everyone understands the term, will never happen”.

The archive, which is marked “secret” and stamped “seen by Taoiseach” has a long line in pen scoring out the section, in apparent disagreement.

A record of a meeting with the IICD in March 1999 showed loyalist paramilitaries the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) unwilling to move first on disarming while the IRA remained non-committal.

The Irish record also stated it was “obvious 100% decommissioning would never be attainable” but that: “If something like 60-70% of currently estimated stocks were decommissioned, this would probably satisfy the public”.

The IICD declared the IRA had decommissioned all of its weapons in 2005, shortly after the republican group formally ordered an end to its armed campaign.

This photo taken on April 10, 1998 shows then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair (right), then-US Senator George Mitchell (centre) and then-Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern after they signed a historic agreement for peace in Northern Ireland, ending a 30-year conflict. (AFP)

This photo taken on March 8, 1973 shows a street near Whitehall, shows the aftermath of an IRA car bomb explosion in London. (AFP)