By Maev Kennedy

The date of July 23, 2012 could have been the day the lights went out, along with suddenly not-so-smart phones, computers, satellite transmissions, GPS navigation systems, televisions, radio broadcasts, hospital equipment, electric pumps and water supplies.

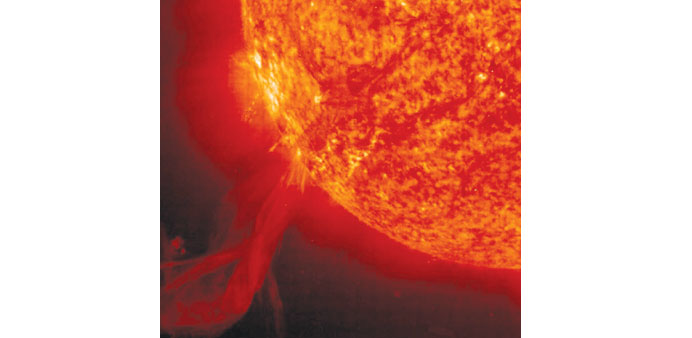

On that day an “extreme solar storm” did its best to end life on Earth as we know it. The sun forced out one of the biggest plasma clouds ever detected at a speed of 3,000km per second, more than four times faster than a typical solar eruption. Fortunately it missed.

“If it had hit, we would still be picking up the pieces,” said Daniel Baker, of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado. “I have come away from our recent studies more convinced than ever that Earth and its inhabitants were incredibly fortunate that the 2012 eruption happened when it did. If the eruption had occurred only one week earlier, Earth would have been in the line of fire.”

With colleagues from Nasa and other universities, Baker has been studying the disaster that wasn’t. If the coronal mass ejection (CME) had hit the Earth, it would have disabled “everything that plugs into a wall socket”.

There would have been major disruption to all satellite communications and electrical fluctuations that could have blown out transformers in power grids. Most people wouldn’t have been able to turn on a tap or flush a toilet because urban water supplies largely rely on electricity.

Nasa has calculated that the cost would have been 20 times the devastation caused by hurricane Katrina, at $2tn.

The storm would have begun with a solar flare, which itself can cause radio blackouts and GPS navigation failures. If the Earth had been in its path, this would have been followed minutes to hours later by the electrons and protons accelerated by the blast, followed by the CME, a billion-ton cloud of magnetised plasma.

There is a lavish amount of data on the storm for Baker and the other scientists to study because, although the plasma cloud missed the Earth, it hit a spacecraft loaded with monitoring equipment.

The solar storm was described as a “Carrington Event” after the solar storm witnessed by the English astronomer Richard Carrington in 1859. He saw the instigating flare, and in the following days a series of CMEs hit the Earth. Given it was the time of steam engines and horse-drawn traffic, this was less crippling than a similar strike would be now, but it did cause telegraph lines across the globe to spark enough to set fire to some telegraph offices. There were spectacular displays of the Northern Lights, seen as far south as Cuba and so bright in places that people could read newspapers outside in the middle of the night.

“In my view the July 2012 storm was in all respects at least as strong as the 1859 Carrington event,” Baker said. “The only difference is, it missed.”

In fact 2012 was a near miss year for the world: Nasa also put out a reassuring press release on December 22, 2012, beginning “if you’re reading this story, it means the world didn’t end on December 21”. It came complete with a video explaining “why the world didn’t end yesterday”.

The flare was a much more plausible reason for panicking than the December stories, which were based on a misunderstanding of the ancient Mayan calendars, said to have come to an end on December 21, 2012. This was widely interpreted as meaning that the Mayan astronomers had a bad feeling about the events of that day. It now appears they didn’t, and the world staggered on.