AFP/Reuters

Paris

French lawmakers have overwhelmingly approved a new law granting the state sweeping powers to spy on its citizens despite criticism from rights groups that the bill is vague and intrusive.

The law has been in the works for some time but gained additional support after a jihadist killing spree in January that left 17 dead and saw the capital gripped with fear for three days.

France is still on high alert as it has received repeated threats from jihadist groups abroad and was reminded of the peril of homegrown extremism when police thwarted a planned attack on a church two weeks ago.

The bill was passed by 438 votes to 86 in the lower house National Assembly, with broad support from both main parties. Only the far-left and greens were strongly opposed.

It will go before the upper house Senate later this month.

Amnesty International has also protested against the legislation, warning that it will take France “a step closer to a surveillance state”.

“This bill is too vague, too far-reaching and leaves too many unanswered questions. Parliament should ensure that measures meant to protect people from terror should not violate their basic rights,” said Amnesty’s Europe director Gauri van Gulik.

The new law will allow authorities to spy on the digital and mobile communications of anyone linked to a “terrorist” inquiry without prior authorisation from a judge, and forces Internet service providers and phone companies to give up data upon request.

In exceptional cases, surveillance agencies will be able to use so-called “IMSI Catcher” spy devices that record all types of phone, Internet or text messaging conversation in an area.

Intelligence services will also have the right to place cameras and recording devices in private dwellings and install “keylogger” devices that record every key stroke on a targeted computer in real time.

The authorities will be able to keep recordings for one month, and metadata for five years.

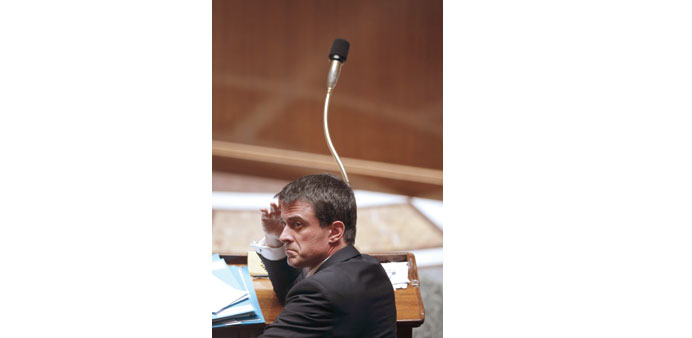

Prime Minister Manuel Valls has fiercely defended the bill, saying that to compare it to the mass surveillance “Patriot Act” introduced in the United States after the 9/11 attacks was a “lie”.

He has pointed out that the previous law on wiretapping dates back to 1991, “when there were no mobile phones or Internet”, which makes the new bill crucial in the face of extremist threats.

Nor was it similar, Valls said, to the widespread intelligence gathering exposed by former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden, sparking an international outcry.

“This bill, which provides a framework to the work of intelligence services, gives them more powers to be more efficient in the fight against terrorism and serious crime,” he told reporters.

France decided to shake up its spy laws after the January 7-9 attacks on the Paris offices of the Charlie Hebdo magazine, a policewoman and a Jewish supermarket that sent shockwaves around the world.

Hundreds of its citizens – more than any other European country – have left to join militant groups such as the Islamic State group (IS) in Iraq and Syria and fears are high they may return to carry out attacks on home soil.

After an Algerian was recently arrested purely by chance before carrying out an attack on a church, Valls warned the country has never “had to face this kind of terrorism in our history”.

Perhaps the most controversial of the bill’s proposals are so-called “black boxes” – or complex algorithms – that Internet providers will be forced to install to flag up a pattern of suspicious behaviour online such as what keywords someone types, what sites they consult and who they contact and when.

A poll published last month showed that nearly two-thirds of French people were in favour of restricting freedoms in the name of fighting extremism.

Only 32% of those surveyed in the CSA poll for the Atlantico news website said they were opposed to freedoms being reduced, although this proportion rose significantly among young people.

However, the national digital council, an independent advisory body, has come out against the proposed legislation.

The group said that it was akin to “mass surveillance” which has “been shown to be extremely inefficient in the United States”.

It also said that it was “unsuited to the challenges of countering terrorist recruitment” and “does not provide sufficient guarantees in terms of freedoms”.

One of the leading worries for critics is a clause requiring Web providers to automatically track suspicious behaviour, relying on metadata rather than the content of communications.

Government agencies could then demand access to personal Web information in cases of particular suspicion.

“Some of us are really worried about a piece of legislation that is unbalanced, gives too much power to the executive branch ... and has the potential to organise a mass espionage of the entire population through modern means,” conservative UMP lawmaker Pierre Lellouche told reporters.

The upper house of parliament will vote on the bill next month.

Valls: This bill ... gives (the intelligence services) more powers to be more efficient in the fight against terrorism and serious crime.