|

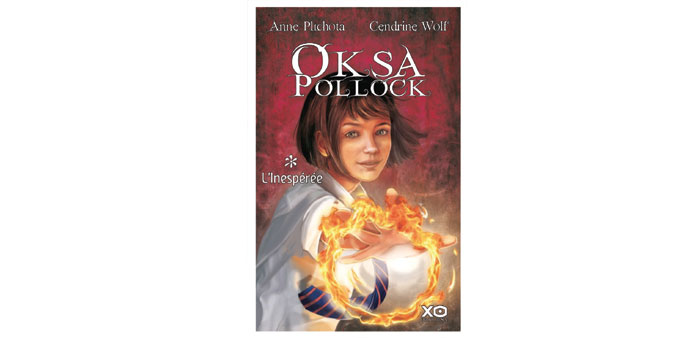

You might think that “Oksa Pollock” is a Harry Potter curse, or one of Professor Dumbledore’s spells. In fact, it’s the latest manifestation of juvenile wizardry’s remarkable grip on the world’s imagination. Perhaps more extraordinary still, Oksa Pollock hails from France. |

Anne Plichota and Cendrine Wolf, both in their 40s, are former librarians, friends for 20 years, who live on the third and fourth floor of the same block of flats in Strasbourg. In 2007, the year in which Harry Potter made his final appearance with the Deathly Hallows, a title known to the French as Harry Potter et les Reliques de la Mort, Plichota and Wolf fell into conversation at a New Year’s Eve party and discovered a shared longing to write for children.

In an interview with the Observer, Plichota says that she had nurtured this ambition “ever since I was 10”, adding she that “Harry Potter gave us courage. JK Rowling is a great role model.”

Plichota, who comes from Ukraine, has a teenage daughter; and so the two would-be writers decided to build a story around a 13-year-old girl called Oksa, a Russian name. Like Harry, she would also have an Anglo-Saxon surname (Pollock), but unlike Harry she would not be an orphan and her adventures would be grounded in hyper-reality.

“She would be strong, but she would be vulnerable, too,” says Plichota. “Oksa is not perfect. She can be brave, but she has weaknesses. She makes mistakes. Even though she is a great magician, she is also very human. She looks like us and feels like us, and could be any of us.”

Plichota and Wolf began to tell Oksa’s story, a tale of displacement in which a teenage girl is brought from Paris to London with her grandmother, Dragomira, and then finds things going haywire. The first of six volumes, Oksa Pollock: The Last Hope, had a winning mixture of jeopardy, heartbreak and fantasy: imaginary creatures, the quest for a true friend, and an epic struggle between good and evil, represented by the teacher Orthon McGraw.

Too much, you might say? But this is exactly what the authors of Oksa Pollock want to celebrate. “What we love about England,” Plichota has said, “is that when we are there we are foreign, but we don’t feel foreign. The taste for fantasy and eccentricity is deeply inside English culture”.

At first, however, nothing went right for Oksa Pollock. The experience of authorship, says Plichota, was “very frustrating. No one was interested. Everyone turned us down”. Editions Gallimard, Harry Potter’s French publisher, showed no interest. Rebuffed, Plichota and Wolf decided to go it alone. They began to self-publish their work, but not online. They wanted a more traditional medium for their work and discovered how to print and promote their books themselves. After two years, they had sold 15,000 copies.

“We learned many things,” says Plichota, recalling long hours pushing trolleyloads of books outside school gates and into libraries. “It was a necessary step.” Then word of mouth kicked in. “Watch out, Harry Potter!” thundered Le Point, “here comes Pollockmania!” Tens of thousands of French schoolchildren were now devouring the adventures of Oksa Pollock in self-published editions produced outside the elite world of French publishing, with no support from the trade.

To the fans, this was a story of literary injustice. Fourteen-year-old Achille, a diehard Pollock fan, wrote an open letter to the magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, demanding a response from the hidebound dinosaurs of the Parisian book world. “We’re angry,” Achille wrote, “because the world of books truly sucks. Even bad books work because big publishing houses go all out to bring their books to be number one and they shower us with advertisements. The fantasy saga [Oksa Pollock] I want to talk to you about is self-published but it’s a bestseller because there are thousands of us in France who have come across it simply through word of mouth and the official website.”

Who knows who was behind this stunt? But finally, once “Pollockmania” became a newspaper story, after three years of unrelenting hard work and self-promotion, Plichota and Wolf were offered a world rights deal by Bernard Fixot of XO Editions.

What followed, according to the Paris daily Le Figaro, was another episode in “a publishing fairytale”. Book rights to Oksa Pollock were sold in 27 countries. Summit Entertainment, the producer of the Twilight movies, acquired the film rights. An Oksa Pollock adaptation is currently in pre-production. Meanwhile, the French sales of the Oksa Pollock books have now topped half a million, with another million worldwide in various translations.

There was, however, one last obstacle to negotiate. Pollockmania remained an essentially French phenomenon. Their deepest ambition as writers was to cross the Channel. Asterix, Tintin and Babar the Elephant had made that journey in the past century, but they were the exceptions. Very rarely are French-language children’s books translated into English.

This reflects a wider trend of British cultural insularity. In the UK translated fiction (including adult titles) accounts for less than 3% of all books sold in Britain. To some, like David Almond, Carnegie-prize winning author of Skellig, this is a cause for concern. “Children need to read the best books by the best writers from all parts of the world,” he says. “But the plain fact is that there is very little children’s fiction published in the UK, and our children are missing out.” This reflects the global dominance of the English language. By contrast, in the EU we find that in Poland 46% of books are translated, with 12% in Germany, 24% in Spain and 15% in France, according to Literature Across Frontiers.

Oksa Pollock could be the French heroine to change that, courtesy of Pushkin Children’s Books, an imprint of a lively new independent publisher, Pushkin Press. Adam , its managing director, aims to rectify the traditional dearth of translated fiction, and believes that the 10-plus market (Oksa Pollock’s demographic) offers a new and different opportunity.

“There is a perception that children won’t ‘get’ literature from other countries,” Freudenheim says. “This is absolutely not true. Just look at the success of Asterix, Emil and the Detectives and Pippi Longstocking.”

Plichota and Wolf are hoping that, when their second volume, Oksa Pollock: The Forest of Lost Souls, is published in February, along with the paperback of The Last Hope, Freudenheim’s hunch will be vindicated. Bernard Fixot, meanwhile, having launched Oksa Pollock into Britain, is waiting for the opportune moment to break into the American market.