A European dispute over supply of Covid-19 vaccines is threatening to unleash a wider political and economic conflict that could stymie global collaboration needed to end the pandemic.

After accusing UK vaccine maker AstraZeneca Plc of favouring deliveries to its home country, the European Union announced a drastic plan to control exports of Covid shots. The retaliatory move may encourage more governments to use economic might – or other means – to protect their interests.

The European Commission’s restrictions “open Pandora’s box,” said Simon Evenett, a professor of international trade at the University of St Gallen in Switzerland. If others respond in similar fashion, “it really would be every man for himself.”

The European Union remains at loggerheads with AstraZeneca Plc after the Anglo-Swedish drugmaker rejected demands that it take Covid-19 vaccine supplies from its UK factories to increase doses going to the bloc.

The squabble is opening a new rift in the global effort to slow a pathogen that’s killed 2.2mn people and inflamed Brexit tensions between the UK and the EU. The bloc is already under pressure to speed up an immunisation campaign that’s trailing those in Britain and the US.

In a sign of how fraught tensions have become, the bloc also announced on Friday that it was seeking to limit exports to Northern Ireland, before retreating from the plan hours later. Introducing restrictions between the Republic of Ireland, which is part of the EU, and Northern Ireland would contravene one of the key principles of the Brexit deal, which sought to avoid border controls after decades of violence.

The EU move prompted a rare show of unity from traditional political enemies in Northern Ireland, who uniformly decried the initial decision. Even with the Northern Ireland issue resolved, the bloc’s actions remain hugely controversial and have been criticised by the World Health Organisation, businesses and governments.

“We agreed on the principle that there should not be restrictions on the export of vaccines by companies where they are fulfilling contractual responsibilities,” president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen tweeted on Thursday.

The likelihood of such vaccine disputes multiplying looms large after dozens of countries imposed export restrictions on masks, personal protective equipment and medical supplies earlier in the pandemic. Governments and companies have tussled in the past over access to drugs like new, life-saving HIV medications that were too costly for some hard-hit countries to purchase, said Thomas Bollyky, director of the global health programme at the Council on Foreign Relations.

AstraZeneca new drugs for cancer lifted earnings above analysts’ estimates as the company moved away from older products losing patent exclusivity. “This is not just a fanciful parade of horribles,” he said. “You could see this escalating.”

If governments do take aggressive steps, others could hold back shipments of key ingredients required to make vaccines, or invoke rights to try to produce shots themselves, though that would be very difficult to achieve without support from the manufacturers, according to Evenett.

The situation could set off “chain reactions that go to unexpected places,” said Richard Hatchett, chief executive officer of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, the organisation that’s worked to accelerate development of Covid vaccines. “It’s really important for countries not to overreact.”

In a show of unity, most European countries started vaccinations around the same time in late December. US re-engagement with the World Health Organisation under President Joe Biden also spurred hopes of global cooperation. But maintaining that isn’t easy in an environment of increasing infections and vaccine supply constraints.

As political pressure rises, “that feeling of solidarity fades,” said Klaus Stohr, a former WHO official who helped mobilise governments and drugmakers to prepare for pandemics.

The stakes of getting economies back on track have also grown. Access to vaccines has become a matter of national security, said J Stephen Morrison, director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Global Health Policy Center. That accounts for the US Department of Defence’s important role in developing and distributing shots.

“Vaccines are an indispensable element of getting out from under this scourge that’s destroying economies,” he said. “If you can’t get to herd immunity fast, that inevitably provokes a security crisis.”

Biden has said he’d use the Defense Production Act, a Cold War-era law, to boost the manufacturing of vaccines and the supplies required to administer them, such as vials and needles. Parts of the act could help increase supply, though other pieces could have a ripple effect for global supply chains, Hatchett said. If the US were to combine that expanded production with export restrictions, other governments would be tempted to follow, Evenett said.

AstraZeneca now has found itself in the middle of a public row over contract terms, accusations of blame and threats to impose limits on vaccine exports. The EU’s drug regulator cleared the company’s Covid shot on Friday, paving the way for a conditional marketing authorisation, and potentially easing supply concerns. Still, frustrations are running especially high across Europe as more contagious versions of the virus emerge, and every step of Covid vaccine production and distribution is under scrutiny.

For months, the EU has faced concerns that it might lag the US and Britain, raising its vulnerability as the virus advanced. Britain in early December became the first Western country to clear a shot, while the US plowed as much as $18bn into Operation Warp Speed, adding to the pressure on the bloc.

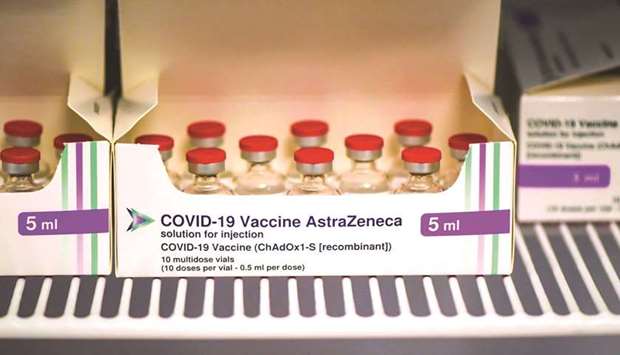

The AstraZeneca Covid vaccine kept in a fridge at the Royal Health & Wellbeing Centre in Oldham, UK. The EU remains at loggerheads with AstraZeneca after the drugmaker rejected demands that it take vaccine supplies from its UK factories to increase doses going to the bloc.