An hour north of Tokyo by way of bullet train, the land is lush and green, framed by thickly wooded mountains in the distance.

This vast rural prefecture in northeast Japan was once renowned for its fruit orchards, but much has changed.

“There has been a bad reputation here,” a local government official said.

Since the spring of 2011, the world has known Fukushima for the massive earthquake and tsunami that killed approximately 16,000 people along the coast. Flooding triggered a nuclear plant meltdown that forced hundreds of thousands more from their homes.

As the recovery process continues nearly a decade later, organisers of the 2020 Summer Games say they want to help.

Under the moniker of the “Reconstruction Olympics,” they have plotted a torch relay course that begins near the crippled Fukushima Daiichi plant and continues through adjacent prefectures — Miyagi and Iwate — impacted by the disaster. The region will host games in baseball, softball and soccer next summer.

“We are hoping that, through sports, we can give the residents new dreams,” said Takahiro Sato, director of Fukushima’s office of Olympic and Paralympic promotions. “We also want to show how far we’ve come.”

The effort has drawn mixed reactions, if only because the so-called “affected areas” are a sensitive topic in Japan.

Some people worry about exposure to lingering radiation; they accuse officials of whitewashing health risks. Critics question spending millions on sports while communities are still rebuilding.

“The people from that area have dealt with these issues for so long and so deeply, the Olympics are kind of a transient event,” said Kyle Cleveland, an associate professor of sociology at Temple University’s campus in Japan. “They’re going to see this as a public relations ploy.”

It was midafternoon in March 2011 when a 9.0 earthquake struck at sea,

The initial crisis focused on the coastline, where thousands were swept to their deaths. Another concern soon arose as floodwaters shut down the power supply and reactor cooling systems at the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Three of the facility’s six reactors suffered fuel meltdowns, releasing radiation into the ocean and atmosphere.

Residents within a 12-mile “exclusion zone” were forced to evacuate; others in places such as Fukushima city, about 38 miles inland, fled as radioactive particles travelled by wind and rain.

The populace began to question announcements from the Tokyo Electric Power Co. (Tepco) about the scope of the contamination, said Cleveland, who is writing a book on the catastrophe and its aftermath.

“In the first 10 weeks, Tepco was downplaying the risk,” he said. “Eventually, they were dissembling and lying.”

The company has been ordered to pay millions in damages, and three former executives have been charged with professional negligence. Crews have removed massive amounts of contaminated soil, washed down buildings and roads, and begun a decades-long process to extract fuel from the reactors’ cooling pools.

All of which left the area known as the “Fruit Kingdom” in limbo.

It is assumed that low-level radiation increases the chances of adverse health effects such as cancer but the science can be complicated.

Reliable data on radiation risks is difficult to obtain, said Jonathan Links, a public health professor at Johns Hopkins University. And, with cosmic rays and other sources emitting natural or “background” ionising radiation, it can be difficult to pinpoint whether an acceptable threshold for additional, low-level exposure exists at all.

In terms of athletes and coaches visiting the impacted prefectures for a week or two during the Olympics, Links said the cancer risk is proportional, growing incrementally each day.

The Japanese government has raised what it considers to be the acceptable exposure from 1 millisievert to 20 millisieverts per year. Along with this adjustment, officials have declared much of the region suitable for habitation, lifting evacuation orders in numerous municipalities. Housing subsidies that allowed evacuees to live elsewhere have been discontinued.

But some towns remain nearly empty.

“People are refusing to go back,” said Katsuya Hirano, a UCLA associate professor of history who has who has spent years collecting interviews for an oral history. “Especially families with children.”

Their hesitancy does not surprise Cleveland. Though research has led the Temple professor to believe conditions are safe, he knows that residents have lost faith in the authorities.

“That horse has left the barn,” he said. “It’s not coming back.”

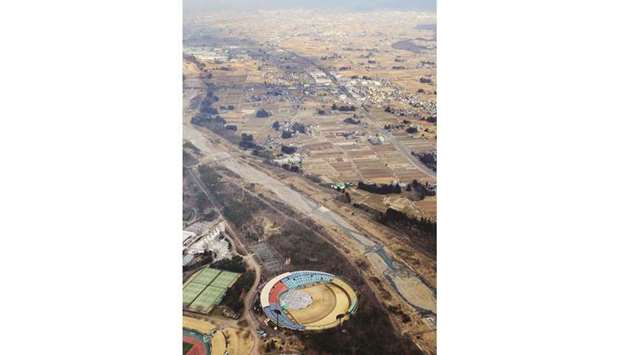

A narrow highway leads west, out of downtown Fukushima, arriving finally at a 30,000-seat ballpark that rises from the farmlands.

Azuma Baseball Stadium was built in the late 1980s with a modernist design, blockish and concrete. Prefecture officials have begun renovations there.

“We changed from grass to artificial turf,” Sato said. “We’re updating the lockers and showers.”

The work is co-ordinated from a small office in the local government headquarters, where two-dozen employees tap away at computer keyboards and talk on phones, sitting at desks that have been pushed together.

Tokyo 2020’s initial bid included preliminary soccer competition at Miyagi Stadium, in a prefecture farther north of the nuclear plant. Six baseball and softball games were relocated to Azuma during later discussions with the International Olympic Committee.

“We made a presentation about the radiation situation and how to deal with it,” Sato recalled. “They understood and we think that’s why they got on board with this idea of the ‘Reconstruction Olympics.’”

Fukushima has spent $20 million on preparations over the past two years, he said, adding that his office has heard complaints from “a segment of the population.”

With infrastructure repairs continuing throughout the region, evacuee Akiko Morimatsu has a sceptical view of the Tokyo 2020 campaign.

“They have called these the ‘Reconstruction Games,’ but just because you call it that doesn’t mean the region will be recovered,” Morimatsu said.

Concerns about radiation prompted her to leave the Fukushima town of Koriyama, outside the mandatory evacuation zone, moving with her two young children to Osaka. Her husband, a doctor, remained; he visits the family once a month.

“The reality is that the region hasn’t recovered,” said Morimatsu, who is part of a group suing the national government and Tepco. “I feel the Olympics are being used as part of a campaign to spread the message that Fukushima is recovered and safe.”

Balance this sentiment against other forces at work in Japanese culture, where the Olympics and baseball, in particular, are widely popular. Masa Takaya, a spokesman for the Tokyo 2020 Organizing Committee, insists that “sports can play an important role in our society.”

In Fukushima, a city of fewer than 300,000, coloured banners fly beside the highway amid other signs of anticipation.

Elderly volunteers, plucking weeds from a flower bed at the train station, wear pink vests that express their support for the Games. On the eastern edge of town, a handful of workers attend to Azuma Stadium.

Dressed in white overalls, they walk slowly across the field, stopping every once in a while to bend down and pick at the pristine turf. Sato remains optimistic.

“Everyone’s circumstances are different,” he said. “Maybe there will be some people who come back to Fukushima because of this.” — Los Angeles Times/TNS

SPOTLIGHT: An aerial view of the Fukushima stadium and it surroundings.