It was the evening of Valentine’s Day, but any plans Cameron Kasky had to celebrate had been obliterated a few hours before when a former classmate came to his high school to spray the hallways with bullets, leaving 17 dead bodies behind when he departed. Now, as darkness descended, Kasky shut the door to his room and plotted a revolution.

Five months later, it is well underway. March for Our Lives, the little band of teenagers Kasky lashed together that night over his cellphone to demand new gun laws, has swollen into a hydra-headed nonprofit corporation with a multimillion-dollar budget, offices in South Florida and Washington, and even its own lobbyist.

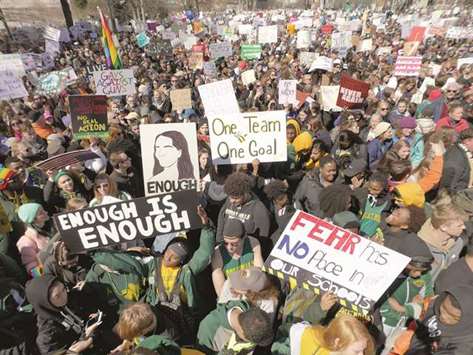

The group, headed mostly by students from Parkland’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, the site of the Valentine’s Day massacre, has staged one mega-protest in Washington, D.C., in March that drew hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, and hundreds of smaller protests across a broad swath of the country from Tallahassee to Bismarck, N.D.

Two busloads of March for Our Lives activists have been crisscrossing America, sowing the seeds of discontent over current gun laws, and they’re starting to sprout: Scores of loosely affiliated groups that share a name and a political agenda with March for Our Lives have popped up across America, even in such scarlet-red states as Arizona.

In Florida and on the road, the students have made one of their central missions encouraging young people to register to vote. In Florida at least, the numbers are encouraging. A recent analysis by TargetSmart, a data firm that works on behalf of Democrats, found that the share of newly registered Florida voters between the ages of 18-29 had increased by eight percentage points in the two and a half months after the shooting.

The political acumen of the Parkland students has left even some of their allies agape. “As remarkable as we acknowledge their leadership has been, we’re still not giving them enough credit,” US Representative Ted Deutch, D-Florida, told the Miami Herald.

The students understandably feel a certain giddy pride that their organising hasn’t succumbed to apathy, torpor or the onset of summer vacation (and, for some of them, the end of high school). In the estimation of many sceptics, the big March 24 demonstration that drew somewhere between 200,000 and 800,000 would be their high-water mark. Instead, the footprint of March for Our Lives is still growing.

“The march was multiple months ago, and we’re still moving,” said Charlie Mirsky, 18, MFOL’s Washington lobbyist.

The momentum of political movements is under perpetual challenge, and veteran organisers say it will be a long time before MFOL can be judged a real success. “Guns are a hugely divisive issue in American politics and culture,” said Todd Gitlin, an NYU sociologist who in the 1960s headed Students for a Democratic Society, one of the major groups opposing the Vietnam War. “That’s not a battle that will be won, or lost, overnight, and it could be years before we can really evaluate the role of the Parkland students.”

A movement lasting years was hardly on Kasky’s mind when he started calling friends on the night of Valentine’s Day. His close-cropped hair and acerbic wit were well known in the Stoneman Douglas drama department. Though never particularly politically active, he was opinionated and had once attended a rally for then-candidate Barack Obama. It wasn’t clear to the friends he called that night what, exactly, Kasky wanted from them.

“He had no idea what I would be doing or what anybody would be doing,” said Mirsky, who, though he isn’t a Parkland student — he attended Spanish River Community High School in Boca Raton — was among the first to get a call. “He just knew he needed me on the team.”

Four or five students showed up the next morning. They met first at Kasky’s mother’s home, then in a Coral Springs park. Using Twitter, they issued open invitations for anyone at all to join them; they volunteered op-ed pieces to the media (CNN used one written by Kasky); Kasky invited the Florida Democratic Party and NPR’s “Morning Edition” show to chat with them.

Within a few days, what would come to be known as the “core group” numbered around five — the bunch appeared on a Time magazine cover — but there are around two dozen key players in the movement. The Stoneman Douglas administration inadvertently boosted their organising efforts by cancelling classes for two weeks, allowing the planning meetings to stretch into something like an endless slumber party.

“Some of us didn’t even go home,” David Hogg, a member of the core group, wrote in a short memoir released last month. “We just stayed at Cameron’s house, sleeping on the couch or the floor and jumping up in the middle of the night with another idea.”

It wasn’t all work. Sometimes they compared who had gotten the most heavy-hitter celebrity retweets. (Their lists of Twitter followers were burgeoning into the hundreds of thousands.) Sometimes they left to attend funerals for their schoolmates. Sometimes they cried. Nobody’s parents seemed to mind.

“It was never gonna be any other way,” said Cameron’s father, Jeff Kasky, who was doing his own organising. (He’s now the president of the Families vs. Assault Rifles PAC, which he started with fellow Stoneman Douglas parents.) “I knew that he needed to do this. Everybody grieves in their own way.”

The students soon learned that, after their cannily directed social media accounts, their most potent weapon was their romance with the cameras that feed the cavernous maw of 24-hour cable news. The whole world was watching, and the students knew it. They would go on camera anytime, anywhere, to demand that lawmakers do something about school shootings.

And the cameras loved them, too; the students had extraordinary poise on the air. Hogg, whose work at the Stoneman Douglas campus TV station made him uncommonly self-assured on camera, quickly became one of the most-recognised faces among the students. He became a lightning rod, sparking an advertiser boycott of Fox News talker Laura Ingraham and fronting a die-in at Publix that prompted the supermarket giant to cease its political contributions — this after it was revealed that Publix had donated $670,000 to Adam Putnam, the Republican gubernatorial candidate who called himself a “proud NRA sellout.” His home was “swatted,” which is when trolls call in a false threat and send SWAT teams swarming.

Another recognisable personality was Emma Gonzalez, the charismatic, buzz-cut president of the high school’s Gay-Straight Alliance, whose looks were striking, her words pugnacious: At a demonstration in Fort Lauderdale a few days after the shooting, tears rolling down her cheeks, she declared that “the people in the government who are voted into power are lying to us,” then added: “And us kids seem to be the only ones who notice and are prepared to call BS.” Her speech went viral, her Twitter followers zoomed past 1 million.

The photogenicity of Hogg and Gonzalez might have started jealous quarrels in some groups. But among the Parkland students, it just spurred more extensive organising. “Very quickly, people on the TV news who mattered became Emma and David,” Mirsky said. “So for everyone else it was very important, including Cameron, to have specific jobs.”

One committee took over the task of outreach to other groups of young activists; another managed the logistics of meet-ups and rallies; a third was devoted to keeping in touch afterward. As the outreach effort grew, the Parkland group decided a national rally and demonstration was an obvious strategy. And money, they realised, was no problem.

MFOL has always been somewhat vague about its finances. But in the early days of organising, a number of Hollywood celebrities, including Oprah Winfrey, George Clooney, Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg, as well as the fashion company Gucci all publicly pledged donations of up to half a million dollars. (Other anti-gun activists, however, caution that funding promises — especially from Hollywood — often come with fingers crossed behind the back.)

Other donors have provided free legal services and office space. A GoFundMe appeal has brought in $3.6 million, and MFOL has also pursued money through The Action Network, a nonprofit corporation that does fund-raising for left-of-centre groups.

Sorting out how much money has come in, and what it’s been spent for, is impossible for anyone outside MFOL. It’s incorporated as a 501(c)(4) nonprofit organisation, which means it doesn’t have to disclose its donors. It can also engage in lobbying and other political activities as long as they don’t become the principal point of the organisation.

So March for Our Lives probably had something well in excess of $5 million to spend this year, but pinning down an exact number is difficult. So is what it’s been spent on — though the group will eventually have to file some financial disclosure forms, they aren’t due for months.

Some of the money has been distributed to Parkland victims, some was spent on rallies and demonstrations, and some has gone to paid staffers. This last is a sensitive point with the students, who bridle at any suggestion that they’re figureheads for professional organisers and lobbyists who do the real work.

“We work with people who do the bare-bones logistical things,” Kasky said. “Other than that, it’s all in-house.” Adds Mirsky: “You’d be very surprised how much is done without the help of adults.”

— Miami Herald/TNS

MAKING A STATEMENT: Marchers attend the March For Our Lives rally to demand stricter gun control laws in Washington, D.C. last March.