It was supposed to be China’s Lord of the Rings. Instead, it turned into another Ishtar, the infamous box office bomb of 1987.

Produced for more than $100 million, the fantasy epic Asura was billed as the most expensive movie ever produced by China’s burgeoning film industry. It aimed to spawn a trilogy based on Tibetan mythology by following a classic Hollywood playbook: pair a time-tested story with sumptuous visual effects, big-name actors and industry veterans.

Then the movie hit theatres last weekend with a thud, grossing just $7 million. In a stunning retreat, the producers quickly yanked the mega-flop from theatres, offering no explanation.

“We apologise to the audience who never got to watch the movie and the inconvenience it caused,” they said on Chinese social media site Weibo.

Asura became the talk of the Chinese film industry after it disappeared from theatres. It was a humbling moment for an industry that is enjoying a record year at the box office and is poised to surpass the US and Canada as the biggest theatrical market by 2020.

The failure of Asura is emblematic of a new reality confronting filmmakers in China. As the Middle Kingdom emulates US studios with increasing budgets and franchise ambitions, audiences are becoming more discerning about what they want to see on the big screen.

The failure of Asura “to launch is the final nail in the coffin for the erroneous belief that Chinese audiences will accept scale and visual effects over fundamental storytelling,” said Peter Shiao, chief executive of film production and marketing company Orb Media in Los Angeles and Beijing.

Box office disasters are nothing new in Hollywood, of course. US film companies have been hammered by such overpriced and misguided efforts as the 1995 dud Cutthroat Island and Walt Disney’s The Lone Ranger in 2013. The late Michael Cimino’s 1980 disaster Heaven’s Gate nearly destroyed United Artists, later sold to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

China has weathered its share of box office flops. In 2010, China had a big miss with Confucius, a bloated biopic about the famous Chinese sage starring Chow Yun-Fat. Officials tried everything to get people to see it, including giving away tickets and pulling the popular Avatar from screens. Nothing worked.

But the failure of Asura has prompted more hand wringing. Some believe local investors will take a more cautious approach to funding big-budget spectacles.

“In the past, it’s been pretty easy for Chinese investors to raise money for movies like this,” said Scott Einbinder, whose company Cristal Pictures is backed by Hong Kong’s East Light Media. “That’s going to change.”

Others see Asura as a natural side effect of rapid growth in China.

“Chinese audiences are growing more and more sophisticated,” said Lindsay Conner, a China expert with the Los Angeles law firm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. “The Chinese film industry can support higher and higher budgets for its films. But the risks and rewards are both greater than ever.”

Beijing officials have long supported the country’s growing film business as part of a “soft power” push to promote Chinese culture abroad.

Although US studios view China as a crucial foreign market, co-productions have fallen flat, as with 2016 Matt Damon fantasy The Great Wall, a $150-million production from Legendary East and Universal Pictures. Though American franchises such as the The Fast & the Furious and Avengers do well in China, others, such as Star Wars, struggle to make the crossover.

Beijing limits the number of movies allowed into the country from the US and other nations as part of a revenue-sharing agreement. American studios have sought to increase the 34-film-a-year quota and the share of the box office grosses they collect from Chinese theatres (they get 25 percent of ticketing revenue, versus roughly 40 percent elsewhere). But the growing trade war between the US and China has derailed those talks.

Nonetheless, China’s film industry continues to grow. Ticket sales are on track to surpass $9 billion this year, largely driven by Chinese productions. Receipts have totalled more than $5 billion so far this year, up 20 percent from the same period in 2017, according to data firm Artisan Gateway.

Indeed, the failure of Asura stands in contrast to local productions that have drawn Chinese moviegoers to cineplexes in droves.

Four of the five highest-grossing movies released in China this year are domestic productions. The top movie, the nationalistic Operation Red Sea, collected $518 million. Last year, the patriotic action movie Wolf Warrior 2 grossed more than $800 million.

More unexpected was the breakout success this month of the dark, low-budget comedy Dying to Survive. The movie, about the owner of a small drug store who smuggles generic medication from India to sell to cancer patients in China, became a national sensation. It has grossed $347 million so far, making it the fifth-highest-grossing movie ever in China.

Its popularity is all the more remarkable for tackling a hot-button issue in China’s highly censored media market. The film has reportedly accelerated government efforts to tamp down the price of cancer drugs.

The success of Dying to Survive shows that China’s tastes are changing, analysts said. Although mass-market Hollywood movies such as Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom continue to wow with high production values, Chinese audiences expect local productions that are relevant to their lives.

“When there’s a homegrown film, people’s expectation of the storytelling is much higher,” said David U. Lee, founder and chief executive of film producer and marketer Leeding Media. “When you don’t have that, you’re in no man’s land.”

The failure of Asura, produced by Zhenjian Film Studio and Ningxia Film Group with financing from Jack Ma’s Alibaba Pictures, left film executives looking for answers.

Asura starred young heartthrob Lei Wu and employed a roster of Hollywood industry veterans, marking the directorial debut of stunt co-ordinator Peng Zhang (The Twilight Saga). It summoned Oscar-winning costume designer Ngila Dickson (Lord of the Rings) and visual effects supervisor Charlie Iturriaga (Deadpool).

But that pedigree couldn’t make up for a concept that failed to interest moviegoers, analysts said. Loosely based on Buddhist mythology, Asura is the story of a young man who must help save a mythical realm from a coup.

The producers alleged Asura fell victim to online trolls, known as water armies because they flood review sites to skew ratings.

The ratings are influential because they reside on online ticketing platforms, which is where 90 percent of movie tickets are sold in China. Users on Maoyan, backed by Alibaba’s rival, Tencent, rated the film a dismal 4.9 out of 10. The Alibaba-owned Tiao Piao Piao, however, gave Asura a score of 8.4.

Asura’s producers, in a Weibo post, called the disparity “the shame of the industry.”

Experts doubted the troll theory. They noted that user reviews on the Chinese website Douban, known to be a more neutral haven for snarky cinephiles, balked at the overuse of digital graphics. Some called it a Game of Thrones knockoff.

One Douban commenter referenced a scene in the movie in which one of the main characters, played by Carina Lau, says, “Everything makes me want to throw up.”

“That explains the whole movie,” wrote the person, who used a pseudonym.

The production companies did not respond to requests for comment.

The decision to promote Asura as China’s most expensive production probably backfired. Citing the price tag, some commenters said it was another example of one of China’s biggest contemporary problems: too much money, and nowhere good to invest it.

Ying Zhu, a professor at City University of New York who focuses on the Chinese entertainment industry, said the film didn’t connect with the current cultural climate.

“Suffice to say that utilising an occidental sci-fi vehicle to carry a … mythical Buddhist tale is a miscalculation,” Zhu said. “The (marriage of) a manufactured ancient Chinese tale and a futuristic Hollywood blockbuster clearly does not sit well with fans of Game of Thrones in China.”

China’s heavily digital society makes the film business less forgiving. Filmgoers are voracious social media users, so when a movie gets a bad response, the audience reacts very quickly. That probably made a bad situation worse for Asura.

Additionally, because Chinese theatres show movies digitally, cinema managers can easily remove underperforming movies from their screens and replace them with a better product.

But adding to the mystery surrounding Asura, it appears it was the producers, not the theatre owners, who pulled the movie out of circulation. Reports suggested that the producers wanted to retool the film for a re-release.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” said Lee, of Leeding Media. “Once the movie is released, the cat’s out of the bag.” — Los Angeles Times/TNS

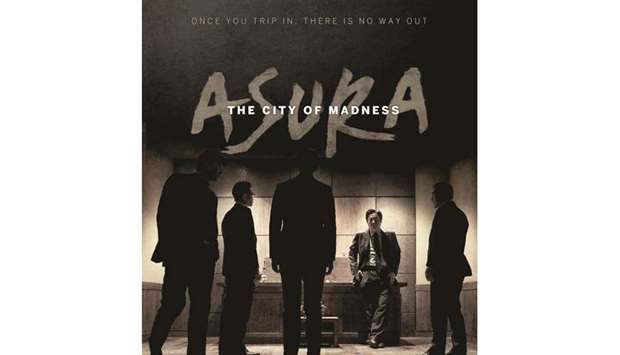

SPOTLIGHT: A publicity still of the over $100 million Asura.