The downtown complex that has housed the Los Angeles Times for decades is filled with notable spaces: the pristine test kitchen, the bustling newsroom and the historic Globe Lobby with its 10-foot-high murals, busts of past publishers and hulking linotype machine.

Then there’s the community room, a drab, workaday gathering spot for employees and visitors that inspires few selfies. But for years, something remarkable resided in this otherwise unremarkable space, largely unseen.

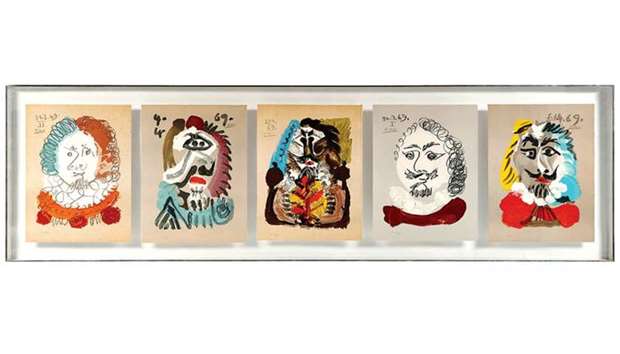

It was art, five pieces framed as one, often hidden behind a lowered projection screen.

The artist was Pablo Picasso.

The five lithographs were abstract depictions of famous literary figures, including Shakespeare, done in vibrant brushstrokes.

They were among the last vestiges of a 110-piece art collection assembled in the late 1960s and early ’70s by the newspaper’s parent company, Times Mirror Co.

Dr Franklin Murphy, the former UCLA chancellor who became Times Mirror’s chief executive in 1968, built the collection with Otis Chandler, who served as Times publisher from 1960 to 1980 and whose family owned the newspaper and its parent.

Works by 20th-century artists Picasso, Rufino Tamayo, Helen Frankenthaler, Milton Avery, Richard Diebenkorn, Isamu Noguchi, Ellsworth Kelly, Saul Steinberg, Claes Oldenburg and many others were put on display in 1973 with the opening of the Times Mirror Building, which adjoined the existing newspaper headquarters.

The artwork was a physical manifestation of the company’s immense power and momentum in those halcyon days, said author Margaret Leslie Davis.

“It was this ethos that Los Angeles had arrived. (They) are not buying Old Masters — this isn’t for the socialites, this isn’t for the ladies page. This is modern and bold, reflective of the new Los Angeles,” said Davis, whose book about Murphy, The Culture Broker, details the creation of the art collection. “This was really radical. It showed tremendous taste — an informed sensibility of what was worth buying and presenting in terms of the Times Mirror image to the world.”

Corporate dining rooms were named after artists — Picasso, Tamayo and Steinberg — whose works hung in them. The five Picasso lithographs were from a 29-piece set of his artwork that had been on display.

“The Picasso Room was exclusive — you had to be an officer in the corporation, a high-up editor to go there,” said Roger Smith, who joined the newspaper in 1977, later became national editor and left in 2013. “I don’t think I got Picasso privileges until the 1990s. It was, ‘Oh wow, I’ve kind of arrived.’”

By the late 1990s, when financial challenges grew and the Chandler family’s patience with newspapers began to wane, the dismantling began. Chicago-based Tribune Co. bought Times Mirror in 2000, and by 2012 most of the collection had been sold off.

But it lived on as newsroom folklore. Veteran staffers told odd and possibly apocryphal tales about the art: that editors were given valuable pieces when they left the newspaper, that a former publisher had works depicting nude women taken down because they offended his sensibilities.

Reporters had cause to revisit this history earlier this year when then-incoming Times owner Dr Patrick Soon-Shiong announced plans to relocate the paper to El Segundo — a move spurred by the 2016 sale of the downtown property to a Canadian developer.

Some staffers began to explore the historic property on nostalgia-laced, self-guided tours. And a visit was paid to the community room to see the Picasso lithographs, perhaps for a final time. They seemed to be the last connection to that vaunted bygone era.

But there was a problem: They were gone.

The artwork had disappeared at some point between 2014 and 2018, a period of great tumult at The Times, as a series of publishers and top editors were shuffled in and out by then-owner Tribune Publishing, which renamed itself Tronc.

The hunt for Picasso was on.

Starting in the late 1960s, Murphy and Chandler sought out artwork that evoked LA’s “new sensibility,” Davis said.

Much of it was contemporary art, some of it created by artists who had deep ties to LA, like Diebenkorn. This, said Kimberli Meyer, the director of the University Art Museum at Cal State Long Beach, reflected the thoughtfulness of the collection.

“To make the choice to show contemporary art by artists who are in California — it’s showing that there is a solid sense of good taste and forward thinking,” she said. “They could have just put up a bunch of photographs, something that was inward looking. The idea that they were thinking about art as an important part of understanding the world — that’s significant.”

Although the paintings, prints and sculptures were put on display throughout Times Mirror Square, as the complex was then known, the Picasso Room got the most attention.

The executive dining room regularly hosted Times honchos and visiting dignitaries, and the sheer volume of the artwork was meant to inspire awe: Chandler and Murphy “wanted a stunning impact when visitors entered the room,” Davis wrote.

“This was a statement — that this was the centre of power in downtown Los Angeles,” she said.

Dining among the Picassos, Tamayos and Steinbergs was an unalloyed pleasure for many. And sometimes, these rooms were the site of surreal encounters.

George Cotliar, who joined the newspaper as a reporter in 1957, recalled a 1980s lunch with Tamayo himself in the Tamayo Room. There to view his works on the walls, the Mexican modernist had brought his wife, Olga Flores Rivas, and she did much of the talking as a small group of journalists lobbed questions at the artist.

“We asked him maybe 15 to 20 questions and she answered … sometimes rolling right over him,” said Cotliar, who then served as managing editor and retired in 1997. “We almost never heard him speak.”

The artwork may have been a point of pride for many, but not everyone saw the value of having it on display.

Mark Willes, who was hired as chief executive of Times Mirror in 1995, had the Picassos and other artwork removed from the dining rooms and replaced with photography and other items that celebrated the work of Times journalists.

Several former and current reporters and editors repeated a widely told story about the decision: that Willes had the artwork removed because at least some of it contained nudity, which he felt was inappropriate.

Willes, who was named Times publisher in 1997 and left in 2000, said in an e-mail that this was false, and that his decision “had nothing to do with the nature of the paintings themselves.”

“I was not offended by them in any way,” said Willes, who later served as chief executive of Deseret Management Corp., which manages assets of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “My concern was that I thought the executive dining room as well as other key places in the building should celebrate journalism and that we should display things that really represented the remarkable people we had in the company and the things they did.”

Times Mirror began to unload some art in 1998 — more than a dozen modern and contemporary pieces it said were too delicate or too valuable to keep in bustling offices.

A Diebenkorn painting titled Ocean Park No. 9 fetched $860,500 at auction, and a sculpture by Alexander Archipenko called Gondolier sold for $574,500. In all, 12 items brought a total of $2.13 million.

Some less valuable works that remained were sold to staff members; others were given to top editors when they left the company, said Elke Corley, an administrator who long maintained the collection and retired in 2001.

Bill Dwyre said in an email that when he was named sports editor in 1981, he was given the chance to select artwork from the company collection for his office. He chose two pieces by Tamayo, but said it became a joke among his reporters that he’d selected the fine art over sports-related items also on offer.

“Some of my staff was semi-mortified because they thought they knew me and now there seemed to be a new element that said I actually knew something about art,” Dwyre said. “I, of course, didn’t know a thing about art. I just liked the way the Tamayos looked.”

Years later, after returning from an out-of-town assignment, Dwyre discovered that they had been replaced by two Picasso lithographs.

Dwyre was told that the Tamayos were being sold and Corley had swapped them with the lithographs. She didn’t want him to go without artwork on his walls, he recalled.

When he retired in 2015, he got permission to take the Picassos with him.

“On my last day,” Dwyre said, “I rolled Pablo Picasso out to my car in a grocery cart and they now hang in my home.”

For decades, The Times’ New York bureau was filled with lithographs, aquatints and collages by the likes of Elaine de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg.

Around 2010, as the office packed up for a planned move, Tribune asked that valuables be shipped back to Chicago, said former bureau chief Geraldine Baum.

Baum, however, was loath to return the artwork to Tribune, which was then bankrupt after real estate magnate Sam Zell’s ill-fated purchase of the company in 2007.

“I remember thinking, ‘I am not sending this to Sam Zell. There is no way,’” Baum said.

Looking to the office’s walls, which were also decorated with posters, she hatched a plan.

“I was a little mischievous and put valueless posters in wooden crates and sent them back to Chicago instead,” she said. “I felt they’d already gotten enough value out of the company. I was representing a news organisation that I cherished.”

She never heard a complaint from Tribune, and the artwork made the move with the rest of the bureau. But it didn’t last long there.

In 2012, amid further cost-cutting, The Times gave up its New York office space and the remaining art.

Seven works were auctioned in May 2012, fetching a total of $6,150, with a Rauschenberg print achieving the highest price of the bunch: $1,700. It was a pedestrian sum for artwork that had been so fiercely protected — and enjoyed — by the bureau’s journalists.

“They gave us this gift of thinking highly enough of us to surround us with beautiful things,” Baum said.

This spring, as Soon-Shiong’s acquisition of The Times was being finalised, no one seemed to have any idea where the five Picasso lithographs had gone.

Times editors and executives said they didn’t know, and a spokeswoman for Tronc referred queries back to The Times’ own spokeswoman, who reiterated the paper’s lack of knowledge on the matter. And with the ownership changes and the sale of the headquarters property, it wasn’t clear even to many in the company who owned the Picassos.

In the scheme of things, the five lithographs weren’t incredibly valuable — they were part of Picasso’s 29-piece Imaginary Portraits series, a complete set of which sold at a 2014 Sotheby’s auction for $93,750. (In all, 500 sets were made.)

Times Mirror acquired its own full set in 1971, bought in small groups for small sums. A trio, for example, cost $228.54 including shipping, according to company correspondence held in an archive at the Huntington Library.

While inexpensive back then, the five pieces took on particular value to some people at The Times, and had even become part of some official tours of the complex in recent years.

Times tour guide Darrell Kunitomi noted their disappearance when he greeted visitors in the community room a few years ago.

“I would raise the AV screen, behind which there were five Picassos. People were impressed to see them,” he said. “One night I raised it, and there was a bare wall. I had no idea as to whether they were taken or stored — they were simply gone.”

Attempts to track them down went nowhere until a source pointed out an online auction firm’s website.

There they were: a crisp image of the five Picasso lithographs housed in a long rectangular frame. There were dollar signs, and a countdown clock.

“Estimate $5,000-$7,000.”

The lithographs were being sold — like all the other art over the years.

According to a person with knowledge of the matter, the Picassos and other art in the building were transferred to Tribune when it bought Times Mirror in 2000. The artwork stayed with Tribune until 2014, when one of the two companies created after its exit from bankruptcy, Tribune Media, received the collection.

Now, this person said, Tribune Media was selling the art via Toomey & Co. Auctioneers. There were 24 pieces in all — most seldom if ever seen by Times staffers — among them lithographs by Diebenkorn, Tamayo and Norman Rockwell. And, of course, the Picassos. — Los Angeles Times/TNS

BLAST FROM THE PAST: Five Pablo Picasso lithographs from his Imaginary Portraits series once hung in a corporate dining room at the downtown complex that houses the Los Angeles Times.