China’s policy makers and local authorities are taking steps to prevent deepening strains in the $11tn bond market from spiralling into a broader systemic collapse.

After a series of defaults and a net contraction in bond financing last month, officials have moved to inject liquidity and pressure creditors to negotiate with embattled individual borrowers this month. Among the examples so far: Central government officials at the highest levels determined that debt-laden HNA Group is facing liquidity issues and should be helped, people familiar with the matter said last week.

Authorities in eastern Zhejiang Province brought creditors together with DunAn Holding Group last month after the conglomerate told the local government it had a capital shortage, according to a filing.

Provincial officials of Hubei in central China similarly intervened in the case of Sunshine Kaidi New Energy, bringing the defaulter together with creditors this month, local media reported.

The People’s Bank of China has been injecting liquidity in money markets amid a bout of turmoil in equities triggered in part by trade tensions with the US; the moves have spurred a rally in bonds. PBoC governor Yi Gang also made clear this week he’ll “comprehensively” use policy tools to ensure stability.

While the moves may not amount to a broad-based effort to arrest bond defaults, they do suggest a fine tuning in China’s financial deleveraging campaign, market players say. The challenge for policy makers will be trying to encourage market- driven efforts to resolve corporate debt issues without reinforcing the old image of a state-dominated financial system.

“We will likely see more private sector companies asking for government support,” said Ivan Chung, head of greater China credit research at Moody’s Investors Service in Hong Kong. “The government still wants market-oriented resolutions - as long as there is no systemic risk,” he said. Authorities “are likely to differentiate whether the distress was caused by poor operations or a liquidity crunch prompted by market panic.”

In the recent interventions, authorities have mostly stopped short of injecting capital or paying off corporate debt, and served as coordinators to establish repayment plans, Chung said. Gary Zhou, director of fixed-income investment at China Securities International’s asset management arm, agrees that the government won’t directly offer credit backing.

Perhaps the biggest beneficiary of intervention has been HNA Group, a massive conglomerate that had $92bn in debt, according to its latest annual report. DunAn Group, an industrial equipment producer and property developer, told Zhejiang officials it had $7bn debt outstanding and asked help to resolve its liquidity crisis, the Financial Times said in May. Sunshine Kaidi’s listed unit has debts of 14.8bn yuan ($2.3bn) due this year.

“If the borrower is an important contributor to local employment and GDP, then regional authorities may be inclined to offer some help,” said Wang Ming, chief operating officer at Shanghai Yaozhi Asset Management. “But it is not easy to meet the interest of all involved parties.”

China has a relatively short history of corporate defaults. It’s only been four years since the nation saw its first domestic delinquency in the modern era. Local governments had long pressured regional commercial banks to roll over debt or offer more loans to keep unprofitable firms alive, seeking to avoid layoffs and subsequent social unrest.

The cautious embrace of defaults has been aimed at encouraging more productive allocation of capital. Premier Li Keqiang has repeatedly said in recent years that zombie companies should be allowed to fail.

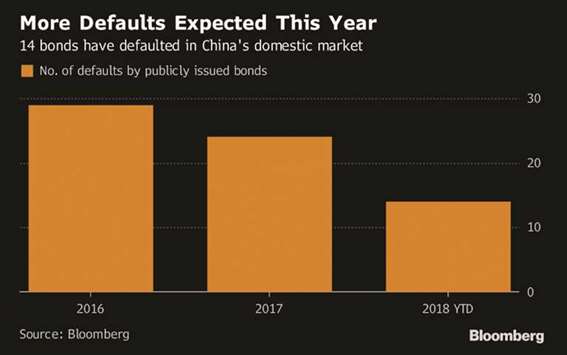

While the number of defaults has risen, the rate is still low. As of the end of May, there were 66.3bn yuan of defaulted notes that hadn’t yet been repaid, or 0.39% of the outstanding corporate bonds, PBoC data show. The PBoC said this month there have been sporadic defaults, which “shows market discipline and the withdrawal of the implicit government guarantee.”

Even so, “any corporate action that has the potential for being destabilising is one where they would tend to get involved,” Jim Veneau, head of fixed income for Asia at AXA Investment Managers Asia in Hong Kong said of Chinese authorities. “It’s fairly clear that the Chinese government values stability.”

.