As the threat of a trade war grows and emerging-market central banks sacrifice growth to protect their currencies, equity investors have their backs to the wall. But in their search for a haven, one name keeps cropping up: India.

The South Asian nation, the fastest-growing major economy in the world, enjoys relative insulation from external shocks as booming middle class delivers enough domestic demand to counter the fallout from protectionism, according to money managers including Franklin Templeton and Newton Investment Management.

Exchange-traded fund house WisdomTree Investments goes a step further, recommending investors allocate as much as 20% of their portfolios to Indian equities.

India is “one of those places that provides better risk-reward compared with emerging markets at large, especially China or more globally-linked countries,” Gaurav Sinha, an asset-allocation strategist at WisdomTree, said in an interview in London. “If I am investing in India, I am investing for the local consumption.”

That might sound brave to anyone who’s been watching India’s performance this year. While stocks are up in local-currency terms, the rupee’s weakness has left investors with losses in dollar terms. Since a global selloff began in January, equities have erased $274bn, equivalent in value to the entire market of Finland. Increased volatility and passive-fund outflows suggest India is no less vulnerable to the jitters than its peers.

The country’s central bank raised interest rates for the first time in four years last week, and Governor Urjit Patel has even gone as far as pleading with the Fed to go slow with its interest-rate increases. With general elections less than 12 months away and Prime Minister Narendra Modi facing prospects of a united opposition, political uncertainty looms large too.

But that’s doing little to deter the bulls. When the dust settles, they say, the country will start to outperform again. And they have history on their side: India was quicker to rebound from the 2008 crisis, handing investors 70% greater returns than the rest of the developing world since then.

“I don’t think our positive stance on India has changed,” said Vikas Chiranewal, a Mumbai-based senior executive director for Franklin Templeton Investments’ emerging-markets group. “The broader market was becoming a bit pricey and some amount of price decline is healthy.”

Propelled by economic reforms that started in 1991 and have been deepened by Modi’s government, India’s middle class has ballooned past 600mn, according to a study by Mumbai University. The nation will become the third-largest consumer economy, with household spending tripling to $4tn by 2025, according to a report by Boston Consulting Group last year. That’s made Indian markets a magnet for foreign investors, spurring flows of $335bn in the past 10 years.

The International Monetary Fund predicts India’s gross domestic product will grow an average of more than 8% annually in the next five years.

“India is the only, large accessible country which has the potential to grow at substantial rates,” Sinha said.

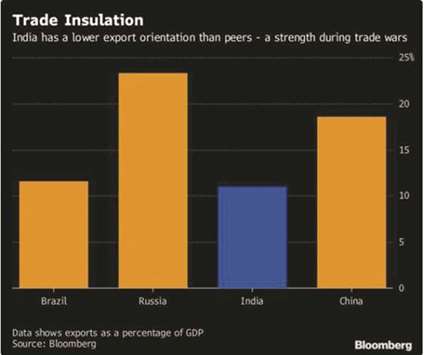

Yet India is less reliant on exports than most other emerging markets. With almost two-thirds of GDP accounted for by consumption, companies have their hands full serving local demand. As a result, exports account for just 11% of the GDP, compared with China’s 19% and Russia’s 23%.

Mumbai’s $2.2tn stock market is primarily driven by investors at home. Foreign-investment flows have accounted for a fraction of the trading even during this year’s declines. The benchmark S&P BSE Sensex rose 0.6% on Tuesday to the highest since February.

Still, signs abound that India’s stock market is overcrowded. Investors have to pay more than $18 for every dollar of projected profit, one of the world’s highest valuations. The country’s sensitivity to oil prices and the approach of the 2019 general elections increase the risk that the market may be volatile for the next 12 months.

“Valuations have become more stretched for the Indian equity market as a whole, but provided the oil price does not continue to rise, we think India does offer relative insulation against protectionist trade policy,” said Douglas Reed, a London-based strategist at Newton Investment Management.

.