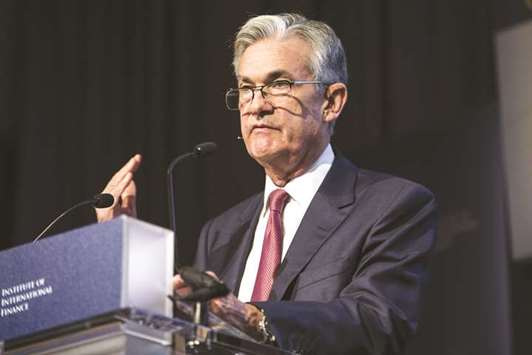

The Federal Reserve’s gradual push towards higher interest rates shouldn’t be blamed for any roiling of emerging market economies, which are well placed to navigate the tightening of US monetary policy, Fed chairman Jerome Powell said.

In a speech that argued US decision-making isn’t the major determinant of flows of capital into developing economies, Powell said the influence of the Fed on global financial conditions should not be overstated, despite it being blamed five years ago for the so-called taper tantrum.

“There is good reason to think that the normalisation of monetary policy in advanced economies should continue to prove manageable for EMEs,” Powell said at a conference sponsored by the International Monetary Fund and Swiss National Bank in Zurich yesterday. “Markets should not be surprised by our actions if the economy evolves in line with expectations.”

The remarks come as investors bet against emerging markets amid concerns about Fed policy. The dollar has soared against most developing-nation currencies in the past month.

Debt sales from countries such as Russia and Argentina have been cancelled or postponed recently as potential buyers – becoming more selective and demanding as US benchmark rates rise – balked at the prospect of faster inflation and widening budget deficits.

Policy makers have started to act, with Argentina’s central bank abruptly raising rates three times, to 40%, to stem a sell-off in the peso. Russia has put the brakes on further monetary easing. Turkey is seeking to bring down its current account deficit. Indonesia is burning reserves to prop up its currency.

Bloomberg Economics ranked 15 major emerging markets to see which is the most vulnerable to rising oil prices, US rates and protectionism: South Africa comes out as having most to lose. That’s because of its combination of oil imports and current account deficit. Thailand – a big exporter – also looks potentially shaky, reflecting exposure to protectionism. It’s also an oil importer. Resilience for Russia reflects its position as an oil producer. Brazil’s low dependence on exports is a source of resilience.

Speaking in Zurich, Bank for International Settlements general manager Agustin Carstens recommended countries build up their international reserves to have a buffer for when markets turn. “Sometimes you know whatever comes in at some point will have to go out, and it’s better you are prepared,” he said.

Pressure is being amplified by a surge in dollar debt across the world’s developing economies, which rose 10% in the year to the end of 2017 – led by a 22% rise in the issuance of international debt securities – according to the BIS. A fifth of emerging markets and middle-income countries have debt levels above 70% of GDP, with Brazil at 84% and India at 70.2%, according to the IMF.

Capital flows into emerging markets are very much a function of investors’ risk appetite, Chile’s central bank chief Mario Marcel said at the Zurich conference. “Building a reliable floating ex rate regime able to cushion the domestic economy from financial and commodity shocks takes much more than courage or statutory decisions - it should be supported by a sophisticated financial and institutional architecture,” he said.

Investors are watching Treasury yields, which hit a four-year high of 3% last month. JPMorgan Chase & Co chief executive officer Jamie Dimon said it’s possible US growth and inflation prove fast enough to prompt the Fed to raise interest rates more than many anticipate, and it would be wise to prepare for benchmark yields to climb to 4%.

A sustained move higher would pressure local currencies and lure away foreign investors. The International Monetary Fund warned last month that risks to global financial stability have increased over the past six months.

“Central banks may have to respond with interest rate hikes if the sell-off intensifies,” said Chua Hak Bin, a senior economist at Maybank Kim Eng Research in Singapore.

Those most vulnerable include Ukraine, China, Argentina, South Africa and Turkey according to the Institute for International Finance.

Still, the world economy’s best performance in seven years has boosted trade and capital flows, which in turn bolstered current accounts and international reserves. Foreign currency holdings among emerging market and developing economies are projected to be $144bn higher this year, according to the IMF. At the same time, inflation remains subdued in most economies.

That means overall buffers are stronger today than five years ago, when the Fed triggered panic selling by signalling a taper of its massive stimulus programme.

“Emerging market fundamentals are in a much better shape,” said Chetan Ahya, chief economist and Global Head of Economics at Morgan Stanley based in Hong Kong. “Almost across the board we have seen improvement in inflation, current account balances and most importantly real rate differentials have been quite solid.”

Conditions vary country by country. Russia, the Czech Republic, Colombia, Brazil and Philippines are among those that look less at risk, according to the IIF. And alternative tools developed since the last crisis – such as macro-prudential buffers – allow central bankers a broader set of options than just rate hikes.

“It will be more of an eclectic response,” said Robert Subbaraman, Singapore-based head of emerging markets economics at Nomura Holding.

In Brazil for example, after the real traded at near a two-year low, the central bank opted to “smooth out currency moves” by boosting the supply of currency swaps – derivatives that provide investors with protection against losses in the currency – which in turn helped reduce demand for dollars.

But few central banks have been tested as harshly as Argentina’s. The bank was forced to raise its key interest rate by a staggering 1,275 basis points to 40% in eight days to help stem a near collapse in the nation’s currency. The peso is down 15% this year.

The rate hikes, coupled with the announcement of tighter fiscal targets, were steps in the right direction, but the peso will remain vulnerable to dollar strength, said Jorge Mariscal, emerging markets chief investment officer at UBS Global Wealth Management.

Powell: Influence of the Fed on global financial conditions should not be overstated.