After a campaign centred on resistance to immigration and trumpeting a strong economy, near-complete results showed that Orban’s Fidesz party snapped up almost half the vote (48.8%).

This will give it a two-thirds majority in parliament and a legislative carte blanche to pursue Orban’s transformation of the central European country into what he calls an “illiberal democracy”.

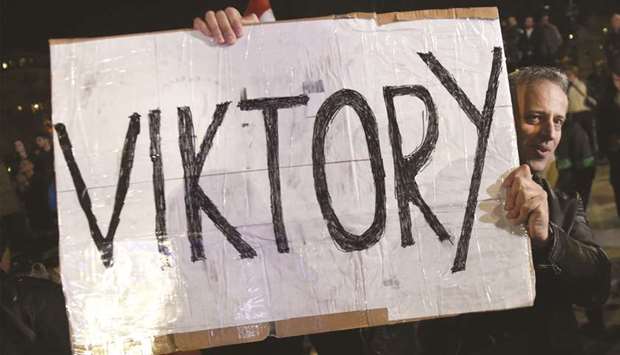

Addressing ecstatic, flag-waving supporters in Budapest late yesterday, Orban said that the “destiny-deciding victory” setting him up for a third straight term gave Hungarians “the opportunity to defend themselves and to defend Hungary”.

His win, which crushed hopes of an upset by opposition supporters, followed strong election performances from other parties portraying themselves as patriotic and anti-system such as in Italy in March and in Austria and Germany last year.

Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) monitors said that “xenophobic rhetoric” and “media bias” in the campaign impaired voters’ ability to make a fully informed choice.

The public broadcaster “clearly favoured the ruling coalition”.

However, congratulations from allies poured in for Orban, long a thorn in the EU’s side, who styles himself as the defender of Christian Europe against the “poison” of immigration and the “globalist elite”.

In Poland, whose government like Budapest has clashed with Brussels over worries about the rule of law, right-wing Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki wished Orban success “for Hungary and for Europe”.

Poland’s deputy foreign minister said that the win confirmed central Europe’s “emancipation” while anti-migrant Czech President Milos Zeman’s spokesman hailed “another defeat for the dehumanised politics and hate media”.

Beatrix von Storch from the Alternative for Germany (AfD) said it is a “bad day for the EU and a good one for Europe”.

“Hungary voted with its heart and its head, ignoring threats from Brussels,” said Matteo Salvini, head of Italy’s far-right League and potentially the next prime minister.

European Commission chief Jean-Claude Juncker will write to Orban to congratulate him on his “clear victory”, a spokesman said.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel also congratulated Orban, with her spokesman saying that despite differences, Berlin wanted co-operation “within the European framework and the values that unite us”.

Orban, 54, became a household name as a young student in 1989 in the dying days of communism with a stirring speech demanding Soviet troops go home.

As one of the brightest stars in newly democratic “new” Europe, Orban co-founded Fidesz and anchored it firmly in the centre-right with a focus on family and Christian values.

The father-of-five learned from a rocky first term as prime minister from 1998-2002.

He bounced back in 2010 with a two-thirds majority, a feat he repeated four years later.

He shook up the judiciary, brought state media under closer control and tacked hard-right during Europe’s 2015 migrant crisis, building razor-wire anti-migrant fences on Hungary’s borders with Serbia and Croatia.

During the recent election campaign he ramped up his attacks on financier and philanthropist George Soros as the malign mastermind of a “global elite” in cahoots with the EU to let in floods of foreigners.

At the same time, Orban has cultivated friendly ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

He also dismisses Hungary being ranked the EU’s second-most corrupt country by Transparency International.

Non-governmental organisations, particularly those funded by Soros – who helped get Fidesz off the ground – have found life particularly hard, and yesterday were bracing for more problems.

Fidesz spokesman Janos Halasz said on television yesterday that bills from a new “Stop Soros” package of legislation would be among the first to go before the new parliament.

According to the bill submitted to parliament before the election, it would impose a 25% tax on foreign donations to NGOs that the government says back migration in Hungary.

Their activity would have to be approved by the interior minister, who could deny permission if he saw a “national security risk”.

Last month, Orban told state radio the government had drafted the bill because activists were being paid by Soros to “transform Hungary into an immigrant country”.

Soros has rejected the campaign against him as “distortions and lies”.

Daniel Hegedus, research adviser at Freedom House, said Orban’s new victory casts a “dark shadow on the future, especially concerning the attacks against the critical civil society”.

Elisabeth Katalin Grabow, a Hungarian-German journalist, said that she and her Ghanaian boyfriend are fearful.

“How could we have children in this country, where hate and racism are now officially part of the governing party’s policy?” she said.

But others were more upbeat.

“Business is good, I have contacts everywhere and I don’t care about civil rights,” construction supplies merchant Janos Kevei, 41, told AFP. “Why change something that’s working so well?”