Want a neat narrative? There isn’t one. Stocks buckled, $3tn was lost, then just as quickly, roughly half of it came back. Nothing quite explains every little twist and turn. Much of it remains a blur. But there are clues to be gleaned from the behaviour of buyers and sellers.

Several key facts stand out. One: a very large sum of money was plowed into equities amid January’s euphoria. Two: even more was yanked out as shares plunged. Three: corporate buyers showed up in force at the bottom.

Combined, the flows are a framework for understanding – not a grand theory of everything, but an account of how money moved during the most tumultuous stretch in two years.

They show how fast things change during a late-stage bull market, a rally that got back on track with last week’s 4.3% rebound.

“There was a technical correction but we saw some fear and some panic and some investors getting burned,” said Andrew Adams, a strategist at Raymond James Financial. “By no means did anyone expect that this selloff would be of this swiftness and magnitude.”

Whatever the role of computers and automated traders as markets bucked and recovered, the events had a recognisable human ring. Investors – many of them of them newly christened, going by account data at discount brokerages – sent $16.4bn to US stock mutual funds and ETFs between January 2 and the market peak of January 26, EPFR data show.

It was a decision they quickly reconsidered. Spooked by signs of inflation, shocked by the sight of traders unwinding bets against volatility, clients pulled almost $27bn from the same set of funds in the next nine sessions. One security, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust, saw $23.6bn withdrawn in one week, separate data compiled by Bloomberg show.

What made the selloff stop is anyone’s guess. It happened at a chart level, the S&P 500’s average price over the last 200 days, that half the world was watching a week ago on Friday.

But who the buyers were is less of a mystery. The Goldman Sachs Group unit that executes share repurchases for clients saw 4.5 times its average daily volume last week, its busiest ever.

“Retail investors were fearful immediately after the selloff, but not the companies,” said Aidan Garrib, macro strategist at Pavilion Global Markets. “Companies have buyback policies that get reconsidered every quarter, so if you told shareholders that you’re going to buy back stock, and then a market blow-up that had no impact on your fundamentals made the price fall more than expected, maybe it’s not a bad thing to step in.”

Tracing fund flows is the easy part. Tracing what drove all the decisions is trickier. This week’s rebound was accompanied by all the things that fuelled January’s rally. Earnings stayed strong - consensus estimates for S&P 500 earnings in 2018 and 2019 rose as companies from Cisco Systems to Deere & Co climbed on profit optimism. Housing starts and consumer confidence were up.

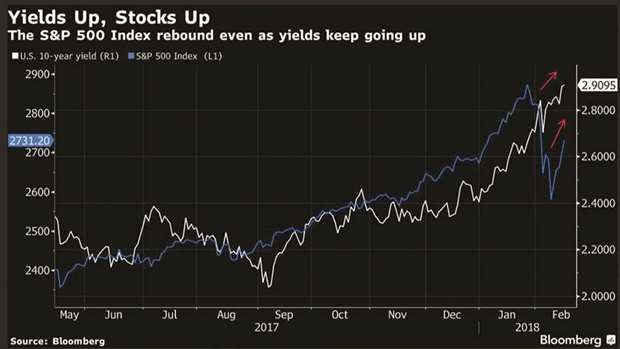

Throughout the last 16 days, investors have been reacting to a rotating assortment of signals, among them the Cboe Volatility Index, inflation data and bond yields. The latter has provided a particularly confusing roadmap for equities. When anxiety first cropped up in the stock market two Fridays ago, yields on 10-year Treasuries had just jumped to 2.84%, up almost 40 basis points from the start of the year.

It’s a level they more or less held for the next five days, as the S&P 500 tumbled 5.2%.

Then the signal went mute. Shares recovered even as yields were topping out at 2.94% on Thursday.

Chalk it up to emotions, says Jurrien Timmer, director of global macro at Fidelity Investments. The fear of missing out meets the fear of going broke.

“On the way down, it just becomes that much more violent,” Timmer said. “But on the way up the bounce is just that much stronger as well. It’s the nature of the beast.”

What happens now? The S&P 500 just rallied for six straight days, retracing 54% of its 292-point loss. The convulsion was painful, particularly compared with the previous year and a half, in which the index never fell as much as 3% from a previous high. At the same time, a year like 1999 was riddled with quick drops and recoveries, en route to a 20% advance. Will this be like that – a rougher road to higher highs?

“For now, we would now have to say, it is indeed another time when buying the dip worked. Will it work forever? No,” John Stoltzfus, chief investment strategist of Oppenheimer & Co, said. “Going forward, concerns about deficit growth and how the Fed will move forward in the process of normalisation – those are both key areas that we believe invariably will cause periods of volatility.”

.