Few people know gate ‘N’ at Mexico City’s airport but three times a week it is the arrival point for the latest group of Mexican immigrants deported by the United States.

Waiting to meet them is Adan Jacome.

Jacome, 45, goes to the terminal to offer the support of a group of immigrants also repatriated to Mexico, and who are the brains behind ‘Deportados Brand’, a small T-shirt business which aims to reunite families and help deported Mexicans start over.

He is a much-needed helping hand for the many migrants who arrive in a practically foreign country but who must find work quickly, despite the stigma of having just been deported.

Upon returning, “doors are closed to them, because people think they must have killed or robbed someone, or been on drugs,” Jacome, who was deported to Mexico after living in Las Vegas for 16 years, told AFP.

Arrests of undocumented migrants have surged since US President Donald Trump took office one year ago.

Law enforcers say they focus on criminal aliens but rights groups allege longtime residents with families and jobs are rounded up on minor infractions.

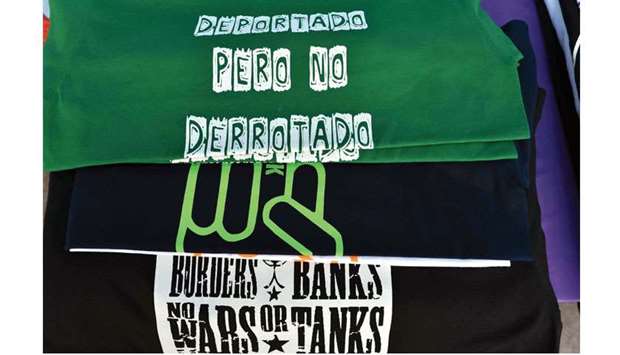

“Deportados Brand,” whose shirts bear slogans such as “We are all gate ‘N’” and “(expletive) Trump,” was born almost by chance at the end of 2016, as Mexico waited with bated breath for Trump to take office after his election win.

Struggling to find work, the five-strong group sold traditional sweets in the street, then went on to create distinctive T-shirts to identify themselves.

The first day they used them was January 20, 2017, the date of Trump’s inauguration.

People liked the shirts, said Gustavo Lavariega, another member of the group who was deported after 17 years in Washington state.

He left four daughters behind.

A few months later, fuelled by the desire to express their feelings using the shirts, the group was screen-printing garments to sell.

It was their way out of the uncertainty which mirrored that of the deported immigrants arriving at the airport.

As well as Jacome, who lends them a cellphone and offers accommodation at the group’s screen-printing facility, they are met by local officials and another organization which gives them a small green bag to keep their things in, instead of the sacks provided when they are deported.

Although some manage a small smile, many new arrivals look as if they have just arrived on another planet.

“It’s a very hard assimilation process. First someone arrives in Mexico and says ‘I can’t believe it, why did they deport me?’ They didn’t want to come back, they had a well-paid job, and that’s where the anger comes from,” said Lavariego, 42.

Ana Laura Lopez, also 42 and one of the most familiar faces in the organisation, had a similar experience when she was deported from Chicago after 16 years, leaving two sons.

She was heading to the airport to sort out her papers in Mexico — with the intention of returning to the US with a work visa — when she was picked up by immigration agents. Now, she cannot return to the US for 20 years.

For her, “everything changed” when she arrived in Mexico. “I had just been robbed of the only opportunity I had, when I wasn’t a criminal, when I had dedicated myself to working. I was in shock for several days,” she recalled.

However, with the business going from strength to strength and winning fans on Facebook, her tone changes remembering the T-shirt design which best expresses her current feelings.

“Intelligent here and there,” it says in Spanish, in a design which mimics the logo of the Chicago Cubs baseball team.

Although they’re enjoying success in Mexico, the group’s members see returning to their homes in the US as an increasingly difficult task, thanks to Trump’s tough stance on immigrants.

“It’s a year that has lowered our hopes of returning home,” says Lopez, at a protest in front of the US embassy in Mexico, during which they present the sacks given to deported migrants. “Every sack has a story. It’s a broken dream, a separated family,” she said.

A view of a stamped T-shirt reading ‘Deported but not defeated’ at a workshop run by deported Mexican migrants in Mexico City.