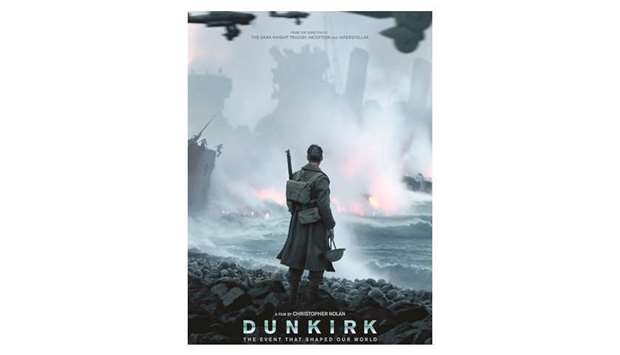

Not much can prepare you for the heart-stopping immersion of Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, his tribute to the World War II battle that looms large in the history and heart of England. The 1940 evacuation of more than 300,000 British soldiers from a French beach, under heavy fire from German soldiers and planes, was aided by a flotilla of small boats captained by civilians from across the English Channel. That show of bravery and solidarity is still spoken of today as “the Dunkirk spirit,” which Nolan presents beautifully in this simply astonishing cinematic achievement.

On a towering IMAX screen the film swallows you whole, and puts you in the middle of the action — on land, on sea and in the air. Nolan puts you on the beach with these young men, as bombs and sand shower down, and gives us a bird’s-eye view from the cockpit of Spitfires dogfighting in the sky. We’re planted on a deserted village street with a group of British soldiers tip-toeing amongst a snowfall of Nazi propaganda fliers. The booming gunshots reverberate through your bones.

Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema have crafted a film that places us in this heightened reality, shooting with IMAX cameras on large format film stock. Everything about Dunkirk is bigger, realer, in images that are equally breathtaking in their beauty and in their terror. Nolan eschewed computer special effects for the most part, striving for as authentic a representation as possible, even strapping IMAX cameras to vintage planes to capture those soaring, vertiginous shots over the open sea.

There are three storylines, named “1. The Mole: One Week,” which takes place on the beach in Dunkirk, “2. The Sea: One Day,” following the small boats from England, and “3. The Air: One Hour,” the story of a pair of Royal Air Force pilots. Nolan intercuts between these events until they all become inextricably intertwined together.

In the script, Nolan has done away with exposition. The story is all that happens there, and we become emotionally bonded to these characters in just witnessing their fight for survival. On the beach, we follow a young soldier, played by Fionn Whitehead in his first feature film, in a nearly wordless performance, through an unspeakably harrowing survival tale, from the streets of Dunkirk, to the belly of a destroyer, through the oil-soaked, fiery sea.

The dramatic scope never wavers from the individual, interpersonal level, though the enormity of the task at hand is never far from mind. Aboard a pleasure yacht en route to Dunkirk, a civilian (Mark Rylance) and his son (Tom Glynn-Carney) and friend (Barry Keoghan) spar with a shell-shocked soldier (Cillian Murphy) they’ve fished out of the sea, who refuses to return to France. On the mole, Navy Commander Bolton (Kenneth Branagh) quietly makes the toughest decisions. In the sky, RAF pilots Farrier (Tom Hardy) and Collins (Jack Lowden) are all that stands between the defenceless soldiers on the beach and German bombs.

Hans Zimmer has composed a score that whines and vibrates with high anxiety. A constant “tick-tick-tick” reminds us of the imminent threat that grows with each passing moment, each bomb and torpedo and bullet, but it’s almost scarier when that ticking clock stops. Nolan almost never lets up the intensity in the remarkable Dunkirk, an instant war classic that finds its power in individual tales of heroism and renders them larger than life. — TNS

ENT