Big Oil entering the heavily regulated European power market isn’t a natural fit today. Yet it makes sense for a future in which consumers want charging points alongside gasoline pumps at fuelling stations, and iPhone apps and smart home devices generate vast amounts of energy-use data that itself becomes a valuable commodity.

“We’re on the cusp of a potentially rather fundamental reorganization of the way that consumers purchase and get access to electricity,” said Rick Wheatley, an executive vice president at Xynteo Ltd, which advises oil companies including Shell on long-term sustainable planning. The oil industry is realising “that things may begin to move much faster” in renewables and the electrification of transport, he said.

Shell’s steps toward selling electricity have so far have been modest in comparison to its vast fossil fuels business. The company pumped 1.85mn barrels of oil and 10.47bn cubic feet of natural gas every day in the third quarter, more than enough to supply the whole of the UK. In contrast, First Utility has no generation of its own, instead buying power wholesale from a Shell unit, and supplies just 3% of the country’s residential energy market.

In October, Shell announced it was buying NewMotion, Europe’s largest electric-vehicle charging provider. In late November it reached an agreement with IONITY - a Munich-based venture between BMW Group, Daimler AG, Ford Motor Co and Volkswagen AG - to start charging stations in 10 European nations.

Eneco, which pointedly shuns fossil fuels on the home page of its website, has a portfolio of sustainable energy projects across northwestern Europe. A Shell spokeswoman declined to comment on whether it was considering bidding for the Rotterdam- based utility or the company’s broader plans in the power sector.

Large oil companies are keen to make small investments now as a way to minimise the difficulty of gaining entry to new markets later on, said Richard Chatterton, an oil analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

“They don’t want to have any potential new opportunity out of their reach,” Chatterton said. These investments “are all about making sure they’re positioned well to take a hold of future opportunities when they become clear.”

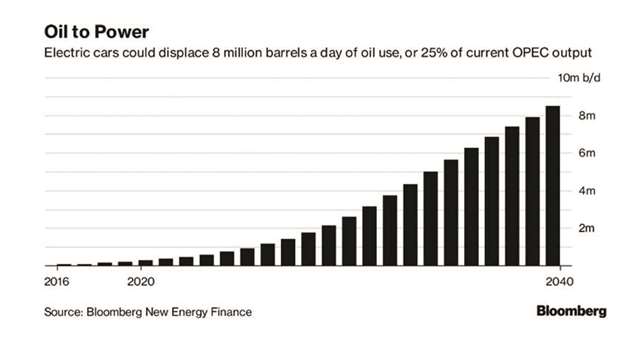

BNEF estimates global power demand will surge 58% by 2040, compared with 2016 levels, with $10.2tn of investment needed in the sector. The research group forecasts that during the same period the growth of electric vehicles will displace about 8mn barrels of oil a day – equivalent to the production of Iran and Iraq today.

Chief executive Ben van Beurden, in a post on Shell’s website earlier this month, said he thinks constantly about preparing for a world where fossil fuels are less dominant. He intends to use the New Energies unit, with a budget of as much as $2bn a year, to ensure Shell remains “a company of the future.”