The temple where hippies once sang is no longer there. The staggered steps at the base of the Maju Dega Temple are the only indication of what once had been there.

The massive Taleju Temple, with its three-storey pagoda roof, is hidden behind scaffolding. At other temples, supporting beams have been driven into the brick walls. White paint is peeling off the Tribhuvan Museum, while grass and shrubs grow atop its marquee.

Ever since the huge earthquake of April 25, 2015, nobody has dared to climb up there.

The quake measured 7.8 on the Richter scale. An aftershock on May 12 was barely weaker. Now, two years later, the royal Durbar Square still bears the scars. And they will be around a long while.

“After the quake, we estimated the reconstruction would take 10 years,” says Christian Manhart, head of the UNESCO office in Kathmandu. “But it’s going to take a lot longer.”

More than 750 historical buildings were damaged in the quake, with 135 destroyed. Until now, less than 10 per cent of the buildings have been restored, says Manhart, who is in the thick of it in the rebuilding effort. “The rubble has been cleared and the temple’s pyramids are still standing. But the upper structure and all the ornamentation are missing.”

Money isn’t the problem. At a donors conference, the international community pledged 4 billion dollars for the rebuilding effort.

Huge signs in the old city centre proclaim who is doing what.

At the neoclassical-classical Gaddi Baithak Palace, where in the past the king was coronated and received foreign dignitaries, a US flag flaps in the wind. The Americans have promised to restore the palace with its tall white columns back “to its former splendour.”

The Chinese have an entire row of billboards in the interior courtyard of the royal Nasal Chowk tower.

They show construction plans and illustrations of how they plan to rebuild the 9-storey Basantapur Tower and piece back together its sal wood balconies from the centuries-old fragments.

“Build back better” is the proud slogan that the Nepalese government proclaimed after the disaster.

But it’s not so simple, if for nothing else than the bureaucracy.

Archaeologists must put projects up for public tender and always choose the cheapest bidders, Manhart says, even though they may have no experience whatsoever with temples and palaces. And these in turn employ the cheapest woodcarvers and stone masons.

“The old balconies are so delicately carved. The figures have such fine facial expressions. This will all be lost if the work is done too fast or rough.”

Just choosing the bricks alone is a tricky task. Special bricks are needed for historical buildings, bricks that can be fired only in the winter. “Some people want only to paste historical facades onto a modern core, but that would be against the Venice Charter,” Manhart says, referring to the 1964 set of guidelines UNESCO laid down for conservation and restoration work.

In March 2016, the Nepalese government agreed that in the reconstruction, only historical materials and building techniques should be used. It is Manhart’s job to keep a careful eye on the work to see that this happens.

“I have already shut down some building sites because they were working with concrete and cement,” he said. “Of course I didn’t make any friends.”

In 2006, UNESCO listed no fewer than seven sites – four temples and three palaces – for Kathmandu Valley.

“This is about prestige,” Manhart says. “A government that loses the World Cultural Heritage status would be criticised forever.”

But UNESCO is not completely stubborn with its principles.

This can be seen at the stupa of Boudnath, the largest Buddhist shrine in Nepal.

The cracks at the base of the dome have been patched over and are gleaming white as ever, and above the painted eyes of the Buddha the 13 golden stages of enlightenment are again shining brightly. When the quake struck, the three top ones broke off.

Nepal decided to replace the entire tower construction, stabilised with four steel beam on the inside. UNESCO did not interfere.

With prayer flags flapping in the breeze, Buddhists from around the world are again circling the stupa. In fact, the stream of pilgrims never stopped, even after the destruction, since the site is holy even without its golden spire.

“Many go in the morning with a gift platter and pray in the temple,” Manhart says. “Even in today’s world of smartphones, young people are deeply rooted in their traditions.” - DPA

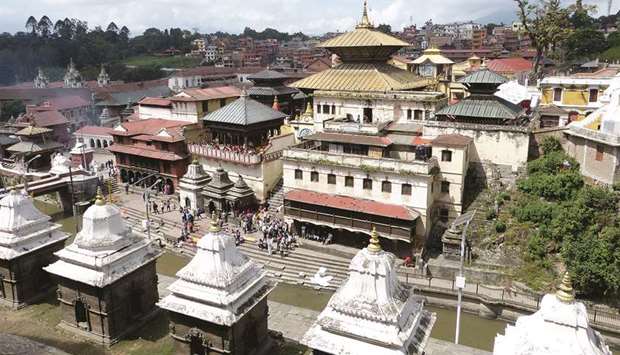

MOSTLY INTACT: In the complex of Pashupatinath in Kathmandu, the 2015 quake left little damage. Other such sites were not so lucky, and rebuilding has been slow-going due to bureaucratic hurdles.