With probably the best batsman in the world and a potent pace bowling attack,

Australia would have been the better side, Stokes or no Stokes

It did not just go wrong on a pavement in Bristol in the early hours of 25 September. The first and most obvious reason why Australia have regained the Ashes at the earliest opportunity is because they are better. And they would have been better, Stokes or no Stokes.

At the head of the Australian team is the best batsman in the series and probably the best in the world. Steve Smith has been superb, rescuing his side in Brisbane and forging the match-winning partnership in Perth.

It was instructive to listen to Smith talking to his inquisitors on ABC radio after he had hit his double century. They were eager to unravel the magic elixir, some quirk of preparation, some clever routine that was peculiar to him. “I just move across to off-stump,” Smith said, “and watch the ball. I don’t think about much at all while I’m out there.”

That is always the way with the great batsmen. The crease is their natural habitat; it is where they are most relaxed and it is where they most want to be in this world.

Smith says he does not like watching cricket much; instead he bats. In this series he has enjoyed reining himself in, enhancing his own pleasure and England’s agony in equal measure. Now he is more interested in great innings rather than great shots. His calmness at the crease, despite all the relentless pre-delivery fidgeting, is reminiscent of Virat Kohli in this generation and Viv Richards and Geoffrey Boycott in another. He loves to bat; he lives to bat.

The problem for England, though, went way beyond Smith. Australia’s bowling attack has been so much more potent. Mitchell Starc, Josh Hazlewood, Pat Cummins and Nathan Lyon had never played a Test together before Brisbane – mainly because of Cummins’s battle with injuries. Now they complement each other brilliantly and they will continue to do so for a while if they remain free from injury.

The three pace bowlers are all quicker than their English counterparts; they gain steeper bounce and Starc just occasionally has managed to swing the ball. They have ruthlessly disposed of England’s tail and there has not been much respite for the early order, either. Meanwhile Lyon is at his peak, confident and combative, spinning the ball vigorously and landing it accurately. Because of the excellence of the pace triumvirate Lyon has usually found himself bowling when Australia have been in a dominant position and he has made the most of it – especially against all those left-handers.

So the Australians have proved that they are better while England could have been much better. The tourists were unable to snatch the few opportunities that came their way. In Brisbane there was scope for a first?innings lead and a strange reluctance to toss the ball to Jimmy Anderson, who has been England’s best bowler here, after lunch. In Adelaide England gambled on the toss but then were timid with the ball until darkness descended on the third evening. In Perth they squandered the chance of a major total having reached 368 for four.

The popular theory when it all goes wrong is to blame the bankers. It is true that Joe Root, Alastair Cook and Stuart Broad have not contributed much. Cook has struggled all tour, despite driving himself relentlessly hard when seeking out extra practice in the nets on his days off. In Adelaide he appeared to have the measure of the pace bowlers only to fall twice to Lyon. In Perth in the second innings he was victim to a freakishly good caught-and-bowled by Hazlewood, but the blunt truth is that his highest score is 37 and he averages 13.83. There will be plenty advocating that he should go now, but he should play in Melbourne and he will. In any case there is no replacement in the tour party. He is still interested.

All the left-handers struggled against Lyon in the first two Tests when the ball turned more than expected. Perhaps there were not enough right-handers in the squad – though there were no obvious omissions. Certainly there were not enough right-handers in the top six, a situation that could have been improved if Jonny Bairstow, rather than Moeen Ali, had been at six from the start. That was a puzzling decision given recent history since Bairstow has always batted higher than Moeen, but it was hardly an Ashes-losing one.

The English bowlers needed help – without lateral movement in the air or off the pitch they were too easily neutered. They squandered their best chance in Adelaide; the Australians could always compensate with their extra pace and bounce. Moreover Lyon was on another plane to Moeen, who has been hampered by a side strain, then a cut to his spinning finger.

There is always the danger in cricket of investing too much importance upon the coaches; they are not omnipotent as in football. Even so, it did not help that England lacked a regular fast-bowling coach. Ottis Gibson and David Saker before him had a special rapport with the pacemen. They talked the bowlers’ language without overcomplicating the process and both generated great trust within the unit. Here on a short?term engagement England had the much?respected New Zealander Shane Bond, who did not have much time to bond but down in his bunker he came up with a lot of cunning schemes. “We have our plans to each batsmen,” we kept hearing. In fact the best plans to almost any batsman is to aim to hit the top of off-stump 90 percent of the time. Those funky fields to Smith soon looked increasingly futile.

Root has been all too visible waving his arms a lot to implement those fields rather than batting for hours. No doubt he knew it would be tough, but not this tough. The extraneous stuff, like the Bairstow head-butt and the Ben Duckett head-drench, were unwelcome, draining distractions. He missed his vice-captain out on the field, one suspects.

There was so much to do that he may have become distracted at the crease, where he is most valuable to England. Root’s touch has been good; maybe he has been straining to impose himself as he senses the team and the tour creaking. Whatever the reason no significant innings was forthcoming from England’s best batsman; they kept coming from Australia’s.

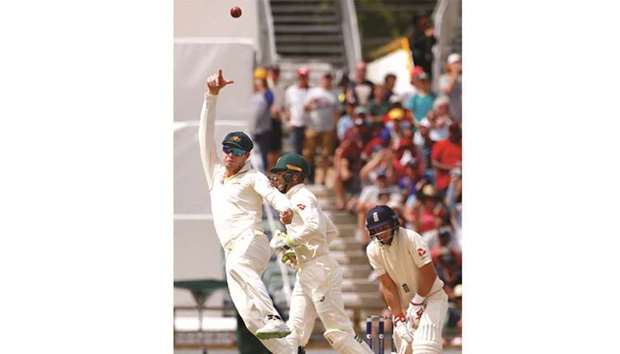

Australia’s captain Steve Smith (left) celebrates taking a catch to dismiss England’s captain Joe Root (right) on Day Four of the third Ashes Test in Perth, Australia, on Sunday. (Reuters)