A poor student who nearly flunked out of high school, Scott Kelly seems an unlikely astronaut. His childhood years in New Jersey were rough; he didn’t apply himself to any subject that bored him; by early adulthood, he was drifting aimlessly as an EMT, enjoying the fast pace but wondering what he should do with the rest of his life. Not exactly the image of the crew-cut, straight-arrow military men like the ones who brought back Apollo 13 with their slide rules.

What he did have was a determination to make something of himself, and the good fortune to pick up a book that changed his life: Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, about the Mercury astronauts and the dangerous, wondrous first years of the US space programme. Eager to join their ranks, he taught himself to study and to persist, and soon he was successfully completing rigorous academic work and making night landings on an aircraft carrier.

Decades later, he became the first American to spend nearly an entire year — 340 days, to be exact — on the International Space Station. He came home in March 2016, and the long-term space habitation’s effects on his body are being studied now as we contemplate a Mars mission. Handily, Kelly has a convenient control subject, who is genetically identical to him but stayed on Earth: his identical twin, Mark Kelly, an astronaut and husband of former US Republican Gabrielle Giffords. (Scott Kelly was in space when Giffords was shot, and in the book he details how he spent agonising hours waiting, not knowing if she had survived.)

Kelly’s new book, Endurance: A Year in Space, a Lifetime of Discovery, is a rollicking tale, well-told, about his journey to making the trip of a lifetime. He shares the big-picture stuff (“I’ve learned that grass smells great and wind feels amazing and rain is a miracle. I will try to remember how magical these things are for the rest of my life”); the entertaining (in preparation for Mars: “Can a pair of underwear be worn four days instead of two? Can a pair of socks last a month?”); and the frightening (cerebral fluid doesn’t drain properly in zero gravity, and it “may squish our eyeballs out of shape”).

The best parts of the book are those in which Kelly answers the burning questions all of us have. How do you sleep in space? How do you brush your teeth, eat breakfast, drink coffee, call your family, work out?

Loss of bone mass, one of the factors Nasa is observing, is a real concern, Kelly writes. He was required to run on a treadmill two hours a day, six days a week — which was often painful — to slow the loss. “Our bodies are smart about getting rid of what’s not needed, and my body has started to notice that my bones are not needed in zero gravity.” As for those well-worn exercise clothes, “there is no laundry up here, so we wear clothes as long as we can stand, then throw them out.”

As for working for a year in space with astronauts from other countries, some he may have met only a time or two, Kelly notes, matter-of-factly, “We have agreed to carry out this huge and challenging project together, so we work to understand and see the best in one another.” He’s been asked many times about what it’s like spending so much time with Russians; he concludes, “I’ve learned that Russian has a more complex vocabulary for cursing than English does, and also a more complex vocabulary for friendship.”

Such cooperation will serve us well when we go to Mars — a feat that Kelly is sure we’ll achieve. After all, the space station is “the work of fifteen different nations over eighteen years, thousands of people speaking different languages and using different engineering methods and standards,” he writes. “In some cases, the station’s modules never touched one another while on Earth, but they all fit together perfectly in space.” — The Seattle Times/TNS

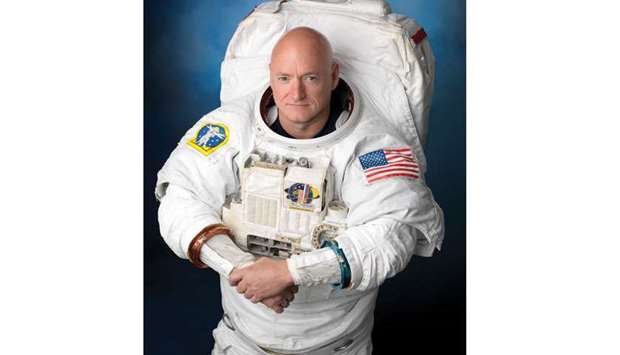

FIRST PERSON: Scott Kelly’s new book is a rollicking tale, well-told, about his journey to making the trip of a lifetime.