Preparing for the demise of Theresa May’s Conservative government, corporate Britain is building bridges to Labour Party leaders. And Labour is reciprocating.

Opposition chief Jeremy Corbyn, an avowed socialist once derided as the man who would make Labour unelectable for a generation, was invited to be a featured speaker at the annual conference of the Confederation for British Industry next month.

Britain’s largest business lobby earlier this month hosted the party’s spokesman on Brexit, Keir Starmer, for a dinner that included representatives from HSBC Holdings Plc, Lloyds Banking Group Plc and Alliance Boots.

A Labour party official said approaches from business leaders or their lobbyists had soared since June’s election, in which Corbyn unexpectedly delivered his party’s best showing since Tony Blair’s in 2001. The new focus from UK Plc reflects concern among executives that Tory divisions over Brexit and May’s electoral failure put her government on borrowed time.

“Since the snap election there’s been more interest in meeting Labour advisers and policy makers” from our members, said Stephen Martin, the director general of the Institute of Directors, which represents 30,000 businesses in the UK and who met with opposition lawmakers at the party conference in September. “Some of the rhetoric coming from Labour has been concerning. They need to recognise the importance of business. It’s easy to knock business, but our membership consists largely of small businesses who are delivering jobs.”

While the next election isn’t scheduled until 2022, there’s speculation that Tory infighting could cause the collapse of May’s government and trigger a vote before then.

Even Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer John McDonnell, who a few months ago was criticized by some in his own party for saying “there was a lot to learn” from Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, is being courted by, and himself seeking out, big business. Two lobbyists speaking on condition of anonymity say that access to McDonnell has become the top demand from their clients, which include global financial services firms as well as retail companies.

Labour has seized the chance to capitalise on this new-found popularity. With May’s fumbling in Brexit negotiations, Starmer’s announcement at the end of August that a Labour government would seek to stay in the single market for an extended period after Britain’s exit from the European Union in March 2019 gave business fresh hope of maintaining unimpeded access to the world’s biggest trading bloc.

“Businesses are turning to Labour for the kind of reassurances they can’t get from government,” McDonnell said in comments to Bloomberg. “We are the only party with a clear Brexit position.”

For business, bridge building has begun largely from square one. Corbyn’s army of activists lacks the cadre of professionals who live in the revolving-door worlds of policy making and lobbying. And while business endorses the party’s stance on Brexit, there are bombs elsewhere in Labour’s agenda — higher taxes on businesses and high-earners, rent controls and the nationalisation of train operators and utilities.

“There are no communications agencies who can actually claim to have a genuine Corbynista insider to help them do this because that would be for them a contradiction in terms,” said Scott Colvin, a partner at the public-relations firm Finsbury.

“Any genuine Corbynista would not be working for a public affairs company or public relations firm.”

McDonnell, for one, may be the one businesses most want to court, but he is also proving the most divisive, and the figure most feared by business chiefs, the lobbyist said. The shadow chancellor openly told a fringe event at the Labour conference last month that he was planning for a possible run on the pound if his party got elected — a move which did not reassure his would-be allies in the corporate world.

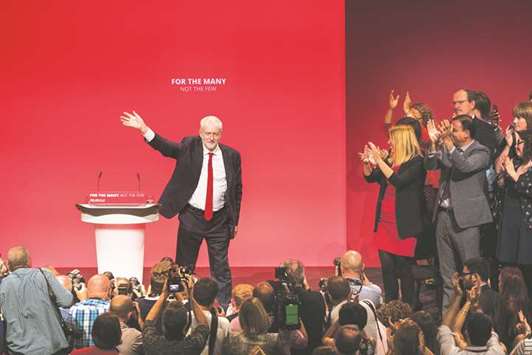

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the UK opposition Labour Party, acknowledges supporters after delivering his keynote speech on the closing day of the annual Labour Party conference in Brighton on September 27. A Labour party official said approaches from business leaders or their lobbyists had soared since June’s election, in which Corbyn unexpectedly delivered his party’s best showing since Tony Blair’s in 2001.