Bill Gates is worried. The tech entrepreneur and philanthropist has been

using his megaphone to warn us of the catastrophic risk posed by

infectious diseases. In the Western world, where mortality from lethal

germs has mostly receded into the background, the burden of infectious

disease can seem like someone else’s problem. But the struggle between

humanity and infectious disease is never someone else’s problem –

certainly not in our globally interconnected society. And while modern

medicine has the upper hand on many old microbial enemies, we should

beware the sinister ability of pathogen evolution to thwart our

cleverest weapons.

Gates is right. The risk of a “big one,” a biological event that

threatens to break down our public health infrastructure and rattle the

foundations of the global order, is out there, lurking. On his side,

Gates has legions of epidemiologists whose dire assessments can seem

abstract. Human history offers us a deeper and more tangible sense of

the unpredictable role that invisible biological enemies have played in

the story of our species.

Take the example of Rome. By any estimate, the Romans built one of

history’s most extraordinary civilisations. For hundreds of years, the

Roman Empire controlled territory stretching from the frostbit frontiers

of northern Britain to the scorching edges of the Sahara. The capacity

to integrate conquered societies into the empire was a source of

strength and staying power. Roman civilisation was a lunge toward

modernity, with greater social complexity and economic prosperity than

ever seen before. And the fall of the Roman Empire represented the

single greatest step backward in the long but uneven march of human

civilisation.

What accounts for this epochal setback? There has never been a shortage

of answers: Loss of virtue (an old favourite, but long out of fashion),

class conflict, fiscal unsustainability, the technological development

of “barbarian” civilisations, or (alas) some failure of immigration

policy. Some 200 answers have been compassed, and the vast majority of

them are human – all too human.

Historians inevitably make the best use of the evidence at their

disposal, and in the last few years, that evidence has been

revolutionised. What we are learning, principally from pathogen

genomics, is that the fall of the Roman Empire may have been a

biological phenomenon.

The most devastating enemy the Romans ever faced was Yersinia pestis,

the bacterium that causes bubonic plague and that has been the agent of

three historic pandemics, including the medieval Black Death. The first

pandemic interrupted a remarkable renaissance of Roman power under the

energetic leadership of the emperor Justinian. In the course of three

years, this disease snaked its way across the empire and carried off

perhaps 30mn souls. The career of the disease in the capital is vividly

described by contemporaries, who believed they were witnessing the

apocalyptic “wine-press of God’s wrath,” in the form of the huge

military towers filled with piles of purulent corpses. The Roman

renaissance was stopped dead in its tracks; state failure and economic

stagnation ensued, from which the Romans never recovered.

Recently the actual DNA of Yersinia pestis has been recovered from

multiple victims of the Roman pandemic. And the lessons are profound.

In the first place, the biological agent of the great plague was a

relatively young species. Y. pestis was not a germ that had existed for

hundreds of thousands of years. To use our contemporary terminology,

when it struck the Roman Empire it was an “emerging infectious disease.”

As old germs evolve new molecular tools, or entirely new germs arrive

on the scene, the results can be tremendously destabilising – a reminder

to modern societies that we must do more than keep track of known

threats.

Second, the Roman pandemic was no parochial affair. The closest known

relatives of the strain that caused the Roman outbreak have been found

in western China. This fact is consistent with the detail provided by

ancient sources that the pandemic erupted on the coast of Egypt, at an

entrepot of the bustling Red Sea trade. The deadly package was ferried

into the empire across the vast Indian Ocean trade network that brought

silk and spices to Roman shores. The plague was, then, an unintended

side effect of incipient globalisation.

And finally, it was an event of mind-boggling ecological complexity.

Plague is a disease of rodents, and the Roman pandemic event involved at

least five different species: the bacterium, the rodents of central

Asia that were the reservoir host, the Black rats that carried the germ

to the west, the fleas whose bite transmits the disease between hosts,

and the human victims. The plague was, in short, a conspiracy of human

civilisation and nature, in a way that the Romans could not have

foreseen or imagined.

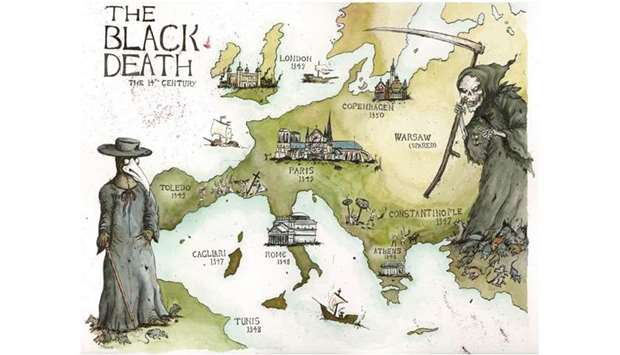

Rome was far from the only advanced society shaken to its core by the

explosive force of infectious diseases. The medieval Black Death sent

some leading-edge polities (like the communities of Italy) backward,

while opening the space for the ascent of others, such as England. The

lethal role of pathogen exchange in the European conquest of the New

World is relatively famous, if still imperfectly understood. The

lightning dispersal of cholera around the globe in the 1810s, and the

1918 Spanish flu, caused by H1N1 influenza virus, are further examples

of the devastation that germs can unleash when human societies offer

them the right conditions.

We are not as helpless in the face of infectious disease as past

societies. We have germ theory and public health and antibiotic

pharmaceuticals at our disposal. But the patterns of history can deepen

our sense of the laws that govern civilisation. Often, those laws are

nature’s laws, not humanity’s. Evolution is the great wild card, and its

awesome power can be checked but never fully conquered.

The threat of pandemic disease deserves to rank among our most rational

fears. Perhaps the experience of bygone civilisations can make that

warning a little less abstract.

* Kyle Harper is senior vice-president and provost and professor of

Classics and Letters at the University of Oklahoma, and the author of

the new book The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an

Empire.