Greenland may have found a path towards its long-term quest for full independence from Denmark through the most unlikely of ways: global warming.

Melting ice is expanding access to mineral resources that Greenland hopes will lead to self-sufficiency. But there’s a long way to go.

Denmark, which retains control of Greenland’s defence and foreign affairs despite expanded home rule since 2009, currently gives the territory an annual grant of some 3.7 billion Danish kroner (about 590 million US dollars) – about two-thirds of Greenland’s budget.

In May, a ruby mine began production in southern Greenland. Though small, it has kindled great hopes among the some 57,000 inhabitants of the world’s largest island, situated mostly above the Arctic Circle and ice-capped across more than 80 per cent of its surface.

“We’ve talked a long time about putting mines in operation, and now it’s finally happening,” says Mute Egede, Greensland’s minister for mineral resources. “This can be the foundation of our becoming a great mining nation.”

Numerous other natural resources are thought to lie under the ice, including oil, uranium and rare-earth elements.

But harsh conditions have made the mining industry hesitant to invest in Greenland, which is banking on other industries as well, such as tourism.

However, the number of tourists is still small: about 70,000 annually, a third of them cruise passengers.

“We’ve got to start from scratch, expand existing hotels and train guides,” remarks Kim Kielsen, Greenland’s premier. “We have a huge task ahead of us.”

Poor infrastructure is a big problem. There are no roads or railways outside the largest towns, so expensive, time-consuming travel by boat or plane is necessary. Plans for more roads and a second international airport exist only on paper.

The sole tourist centre is Ilulissat on the western coast, which has about 4,500 inhabitants and few roads.

A walk from the harbour – home to a large seafood processing plant – to the Icefjord – sea mouth of a glacier and a Unesco World Heritage site – takes you past austere souvenir shops and snack bars.

Tour operator World of Greenland is nearby. It offers whale safaris, iceberg sightseeing, helicopter flights over inland ice and visits to sled-dog handlers, who, besides transporting fish, now give excursions for tourists as a small sideline. Many speak no English and only a little Danish.

“Being so dependent on fisheries makes the economy very vulnerable,” notes Maria Ackren, a researcher at the University of Greenland in the capital, Nuuk, population 17,000.

The magic word is “diversification” into mining and tourism. But that’s not enough.

“To achieve independence, we’ve got to improve education,” Kielsen said.

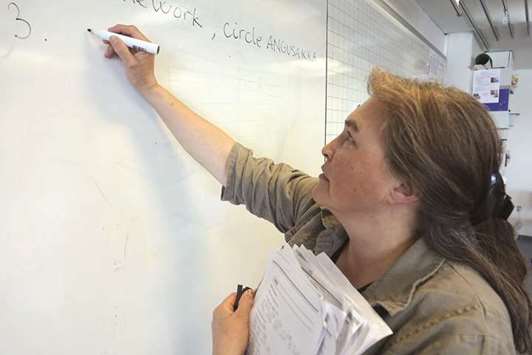

In a seventh-form class in Nuussuaq, a district of Nuuk, teacher Inger Platou is having a hard time making herself heard.

A girl has taken off her shoes and is sitting, facing backwards, on a table. Another is giving herself a beard of soapsuds at the washbin, while a third is taking selfies and listening to loud music.

Just 12 of the 19 pupils have bothered to show up at all. “It’s a difficult class,” says Platou, 61.

Social problems are rife in Greenland, and many parents leave their children to their own devices. Hashish and alcohol abuse are common.

Since the teachers doubt whether all the pupils are properly fed at home, they have a meal at school. Lea fills up her plate and announces: “When I’m done with school, I want to move to Denmark.”

The dropout rate at Greenland’s schools is high, notes Idrissia Thestrup, a Visit Greenland staff member. Many of those who do finish school see no future for themselves on the island and leave, a loss to the economy of valuable workers.

Roughly 80 Greenlanders are employed in the new ruby mine. Another small mine is to start operation at the end of 2017.

“We try to use as much domestic labour as possible,” Egede says.

But for larger projects – a zinc mine in northern Greenland, for example – there’s a shortage of qualified miners.

Although many licences have been granted for exploitation of resource deposits, most projects remain on hold. Receding ice due to climate change may entice more investors to take a chance on Greenland.

“If more land is accessible, larger areas can be explored,” Egede said, adding he wasn’t worried that global warming could harm Greenland’s environment.

“We’ve always adapted to nature. So we’ll manage what’s coming.” - DPA

Inger Platou is a teacher of a seventh-form class in Nuussuaq, a district of Nuuk. Social problems are rife in Greenland, and many parents leave their children to their own devices.